The story of how Ngolo Diara came to rule the Bamana Empire lies in the gray space between folklore and solid history. The tale, as recorded by Bambara griots in southern Mali, is about the folly of standing in the path of destiny. It also makes a template for an RPG adventure that, depending on how you spin it, could be funny, pulpy, or grindingly dark.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Image credit: GMason. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

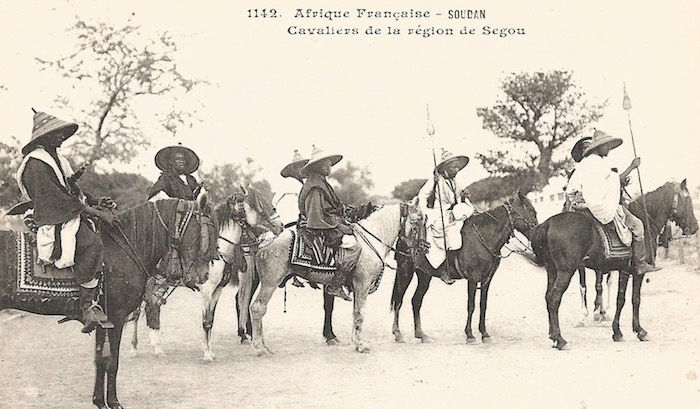

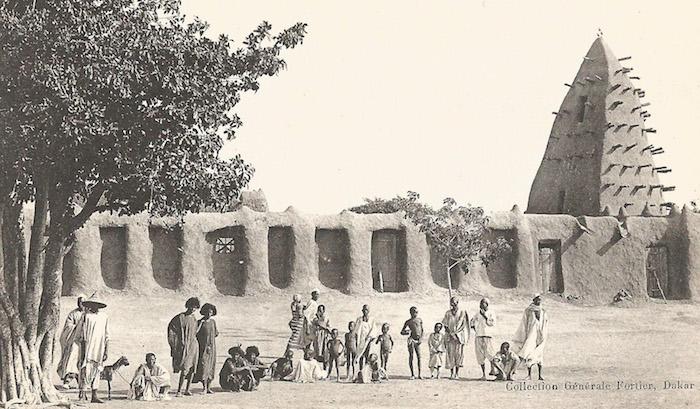

Between the Sahara and the verdant savanna to the south, there is a scrubby intermediate zone called the Sahel. It stretches 3,000 miles across Africa, from Senegal to Sudan. The western Sahel (roughly Mauritania to Niger) has been dominated by empires for over a millennium – though little of our knowledge in this area is exact. The Soninke kingdom of Ghana (no relation to the modern nation) ruled from perhaps the time of Rome until it was replaced by the Mandinka empire of Mali around the 13th century. The Songhai overtook the Mandinka perhaps 200 years later, and the Bambara then rose to prominence around 1600 or 1700 with a kingdom they called Bamana. Bamana fell to the Toucouleur in 1862, and then the French rolled through in the 1890s. Thus, the Bamana Empire straddles the boundary between the medieval empires of which we know so tragically little and the comparatively well-documented colonial occupation.

Fortunately, we have an interesting source of oral history for the Bamana Empire: bards. West Africa has a rich tradition of bards, usually called ‘griots’, and Bambara griots have preserved the history of Bamana, often in song. I’ve heard historians grouse that oral history “isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on,” and there’s certainly something to that. But griot stories of Bamana heroes and kings are of such recent origin that it’s tempting to take them seriously, especially when bolstered by one of the rare surviving written records. All of my hand-wringing in an earlier post about written sources elsewhere in Mali also applies here.

In any case, the story I am about to tell about King Ngolo Diara is not meant to be taken literally. But it is known beyond doubt that Ngolo Diara was a king in Bamana until about 1795. The rest of the story tells us about Bambara values, about Bamana’s institutions, and about what the Bambara of today believe their ancestors saw as praiseworthy or deplorable.

Ngolo Diara was the nephew of a minor village chief. When he was four years old, a magician was casting divinations in Ngolo’s village. To everyone’s shock, the magician announced that little Ngolo would rise high above his uncle and become king! Ngolo’s uncle grew jealous. “I have four healthy sons. Why should my nephew have this great future ahead of him when my own sons won’t get anything of the kind?” So he plotted a way to get rid of Ngolo.

At tax time, Ngolo’s uncle went to gather everyone’s contribution to the village tax. Ngolo’s parents were poor and sick. By Bamana law, they didn’t have to pay taxes. But Ngolo’s uncle insisted, and demanded they hand over the boy. With tears in their eyes, Ngolo’s family waved him goodbye, and his uncle took him far away to the capital of Ségou to give him to the king as a slave.

On the road to Ségou, Ngolo and his uncle stayed in a number of villages and sought hospitality from a number of chiefs. These chiefs understood that the uncle was bringing cowries to the capital to pay the village tax, but why did he have this little boy with him? Ngolo’s uncle explained that the boy was destined to be king, and he wanted the child out of his village. These chiefs all tried to talk the uncle out of this folly. No one had ever presented a freeborn Bambara child as a slave in lieu of taxes. Some even summoned Islamic scholars, who confirmed the child’s destiny. (The Bambara had not yet converted to Islam, but valued Muslim scholars for their knowledge of the mystic sciences.) Many of the chiefs presented little Ngolo with gifts, hoping that when he was king, he would remember their generosity.

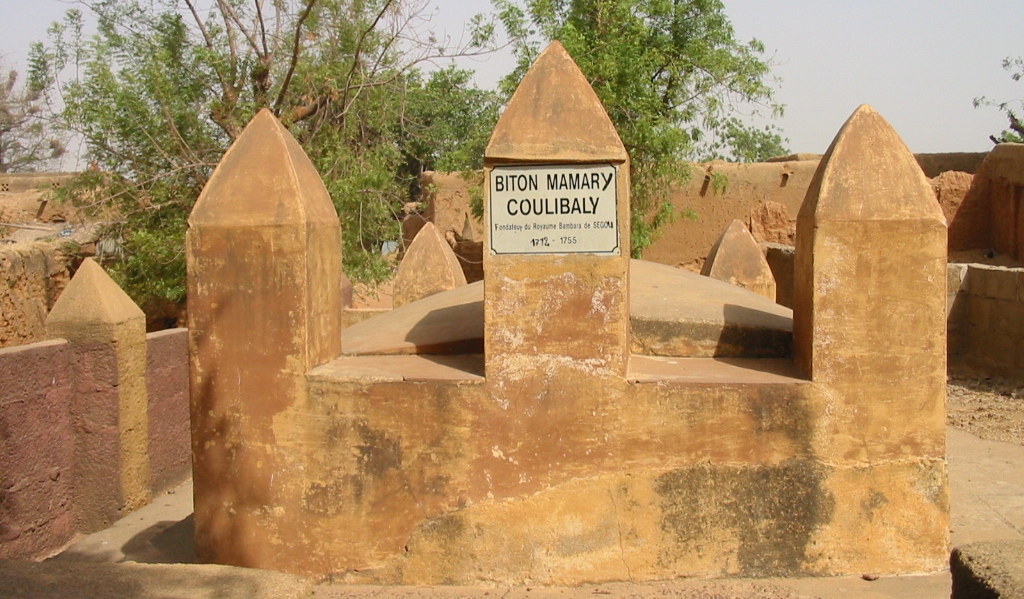

When little Ngolo was deposited at the capital of Ségou, King Biton Mamary didn’t know what to do with the boy. He gave Ngolo to his favorite wife, who promised to raise him as her own child. But soon rumors reached the court that Ngolo was fated to become king. Biton Mamary didn’t like the sound of that. He had sons of his own. If little Ngolo became king, did that not mean Biton Mamary’s sons wouldn’t? The court’s Islamic scholars tested Ngolo’s fate and confirmed, alas, he was destined for the throne and there was nothing anyone could do about it.

Biton Mamary resolved to kill the child. But even a king is bound by law and custom; he couldn’t kill Ngolo out of hand “with a cold knife”. He had to trick Ngolo into committing an infraction for which he could be executed. Biton Mamary said to himself, “Ngolo is only a boy. I will set him a task that is easy for a man. When Ngolo stumbles, he will have failed his king and must be put to death.” So Biton Mamary gave Ngolo a nugget of gold and asked him to keep it safe. Someday, Biton Mamary would ask for it, and then Ngolo must produce it and show he had kept his king’s treasure secure. Biton Mamary was sure little Ngolo would lose the nugget. But when the day came, Ngolo proudly produced the gold! Biton Mamary tried the trick again, but Ngolo sewed the nugget into his belt so he would be sure not to lose it. Biton Mamary ground his teeth, and Ngolo remained alive.

The king’s sons heard of their father’s schemes. They stole Ngolo’s clothes, removed the nugget, and threw it in the river. When Biton Mamary asked for his gold back this time, Ngolo had to confess the truth: that last night, under cover of darkness, someone had stolen the nugget. He couldn’t produce it. Biton Mamary gave Ngolo until sunset to recover the gold or he would be executed.

Ngolo went to his adoptive mother, and she went to a magician. The magician told her, “my divining sands speak, but I don’t understand them. They say you should go to the river to take care of your laundry.” The king’s favorite wife did as she was told. While she was washing her clothes, a fisherman approached her. He’d caught a beautiful carp and wanted to offer it to the royal household for their dinner. She thanked him, and when she cut the carp open to prepare it for supper, what did she find in its stomach but Ngolo’s golden nugget! Ngolo returned the gold to Biton Mamary and, on his mother’s advice, told him, “Your highness, I am only a child. A child should not serve as a treasurer to a king. It is too much responsibility.” Biton Mamary reluctantly agreed and took back the nugget.

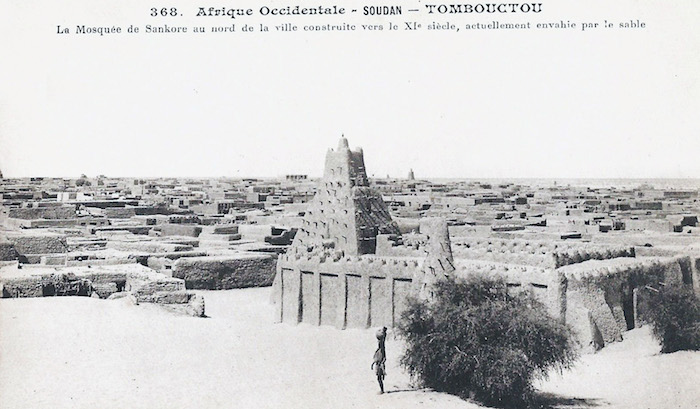

Next, Biton Mamary tried sending Ngolo away. He gave the boy to an emissary to Seku Mochtar Kadiri, an Islamic scholar in Timbuktu, on the northern edge of the Bamana Empire. Ngolo was to be a gift to the great scholar. But when Ngolo and the emissary reached Timbuktu, Seku Mochtar Kadiri saw the boy was special. Because of his knowledge of the mystic sciences, the scholar could see light radiating from Ngolo. He told him, “Ngolo, I can see that you will one day be king and found a new dynasty of kings. If I were to take you as my slave, you would avenge yourself upon me and my family. I will send you back to Ségou, and I will have the emissary tell Biton Mamary that there is no way to avoid what is coming. Destiny winds like a river; it always reaches its end.” On the road back to Ségou, the emissary begged Ngolo’s forgiveness, and Ngolo promised the emissary that no harm would come to him or his family if or when Ngolo became king.

Biton Mamary tried other tricks to rid himself of Ngolo, but none worked, and Ngolo grew into a man. As a last effort, Biton Mamary sent him to act as a tax collector on the wild borders of the empire. Surely some brigand or djinn would do away with him! Instead, Ngolo made a fast friend in the hinterlands to whom the king owed a favor. The friend soon approached the king, asking that Ngolo be permitted to marry the king’s daughter. Biton Mamary gave up. “It is clear there is no magic strong enough to deflect the river of destiny. Ngolo Diara may marry my daughter.” Ngolo married the king’s daughter, joined the palace guard, and became renowned as a warrior.

A few years later, something remarkable happened. Biton Mamary died, and Ngolo did not become king. Biton Mamary’s eldest son succeeded him, and Ngolo said nothing to stop it. Then that king died, his brother succeeded him, and Ngolo still did nothing. But this new king was cruel and twisted. Other members of the palace guard met in secret and decided to kill him. The next morning, when the assassination was discovered, the palace guard named their senior member as his successor. Still Ngolo did nothing. When that king died, the next-senior-most member of the palace guard succeeded him. Several kings came and went this way, and still Ngolo did nothing – until finally a king passed and Ngolo was the senior-most living member of the guard.

Image credit: Released under a CC BY-SA 2.0 FR license.

Thus, Ngolo Diara became king without ever working towards it. But his destiny was not yet complete, for Seku Mochtar Kadiri, in distant Timbuktu, had predicted Ngolo would found a dynasty. Ngolo’s oldest son did not trust the palace guard. He tricked the guard into an ambush and began gunning them down. The guard surrendered, and swore that after Ngolo Diara died, they would not appoint one of their own to replace him, but would let his line continue as the kings of Bamana. As with ascending to the throne, Ngolo founded a dynasty without intending it.

The griots have a saying: “One may travel to Timbuktu by night without seeing anything.” It means that if you if you get in a canoe in Ségou on a moonless night and let the current take you down the Niger River, you will see nothing of the countryside you’re passing through. And yet, without your knowing anything about your journey, you will arrive downstream in Timbuktu. Destiny is the same way. It is impossible for men to know how destiny will be carried out, yet all the same it will.

Kings railing against fate is a staple of mythology the world over, but I love the distinctive flavor this story has. Biton Mamary is determined to pursue his goals while still respecting the legal and customary restrictions on his rule. Ngolo Diara is content to let fate take its course, never once lifting a finger in his own defense.

In an RPG context, what if a ruler in your fictional setting presents your PCs with a similar problem: there’s this NPC who’s destined to become the next ruler, and that cannot be permitted to happen. Can the PCs prevent it? Let them make one or two attempts that you thwart with happenstance, like the fish with the gold nugget in its belly or the scholar who can see destinies. What do the PCs do when faced with such an apparently-impossible task? Do they apologize to their target and placate him or her like the emissary to Timbuktu or the chiefs along the road to Ségou did? Do they try a more direct approach, figuring that if kings cannot kill with a cold knife, perhaps they can?

The above scenario makes it likely the PCs will find an excuse to spare their target, and maybe even do him or her a favor. But maybe you don’t want things to go that way. Maybe the king is a useful NPC and you don’t want to see him get replaced. In that case, first don’t make the usurper a child. If their target is an adult, most players will feel less conflicted. Plus, consider making the usurper a scumbag – someone the PCs actively don’t want to see on the throne. Heck, if there’s an NPC from a previous adventure the players came to despise, have the prophecy be that that NPC is going to be king, so the players have a personal stake in it!

If you do keep the NPC as a child (hoo boy, you’d better know your group before you try something this charged), the scenario might benefit from a complication taken from another griot tale of Bamana, this time the Epic of Bakaridjan Kone. The epic (much longer than the tale of Ngolo Diara) begins with a similar problem. The king knew Bakaridjan was destined to succeed him and didn’t want that to happen. But in the epic, the king’s sons actively tried to kill the young upstart. They tied him up, beat him savagely, and left him in the bush to die. Three days in a row they did this, until the young upstart could take it no more and slew the eldest among them. This was a tragedy twice over – that boys should do such things to one another and that the king’s oldest son should be killed. If while the PCs are trying to get the kid disqualified from rulership or are tricking him or her into an act where execution can be justified (within the rules of the society), what do they do if someone else is just straight-up trying to murder this kid? How do you handle that? If the kid lives and becomes ruler, they will surely remember that you knew about the assassination attempt and did nothing to stop it. If they die, you failed the king because you didn’t get rid of his threat – someone else did. And if you intervene, you just saved the person you’re trying to get rid of! If you do something like this, have the plot to kill the kid be something slow, like a curse or gradual poisoning with heavy metals. That way, the PCs have plenty of time to wring their hands rather than needing to decide in an instant.

–

Source: The Heart of the Ngoni: Heroes of the African Kingdom of Segu by Harold Courlander & Ousmane Sako (1994)