Herculaneum was a Roman town buried in 79 A.D. by the eruption of the volcano Mt. Vesuvius. These days, it’s a bit of an afterthought to the neighboring buried ruin of Pompeii. But from 1738 to 1748, before excavation began at Pompeii, the excavation at Herculaneum was the big exciting hotness of Europe. Except it wasn’t an archaeological excavation as we understand them. It was a mining operation, with pit shafts, horizontal tunnels, and forced labor. It was a lot like a coal mine, except the miners were harvesting Roman art for the court of the King of Naples. It’s a truly bizarre story, bound up in European international politics and centuries of local history. It also makes one hell of a dungeon crawl – and one where the dungeon can be a diplomatic and investigative affair if you want it to be!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Robert Nichols. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Robert, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

In 1738, Naples got a new king: Charles VII. The War of the Polish Succession – one in the endless string of interchangeable wars that roiled Europe for 400 years – ended with a peace treaty that granted the Spanish branch of the House of Bourbon control of the Kingdom of Naples, provided the King of Naples remained a different person from the King of Spain. The treaty recognized as the King of Naples the man who’d conquered the kingdom during the war: Charles VII, the 22-year-old son of the King of Spain. But Charles was in a bit of a political pickle. He was King of Naples (and Sicily too), but he wasn’t Neapolitan, nor did his family have much in the way of local connections. Worse, the only reason a Bourbon had been permitted to rule Naples was the promise that Naples would not function as an appendage of the Spanish state. To be perceived otherwise risked upsetting Europe’s delicate balance of power and plunging the continent back into war. The Spanish Charles VII had to build up an independent Neapolitan identity for himself and for his brand-new court – and he had to do it fast.

Charles decided a great way to do that would be to surround himself with symbols of Naples’ long and remarkable history. Coincidentally, folks only a few miles outside Naples were digging up statues and other works of art from where the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum had once stood, before they were buried under meters of ash in 79 A.D. Charles’ own wife had inherited the finest of these recently-unearthed statues. The art from these sites was valuable, it was Neapolitan, and Charles wanted it. The most promising site was the former town of Herculaneum.

Pompeii and Herculaneum are often portrayed as grand rediscoveries. As is so often the case, this wasn’t so much a novel discovery as it was publicizing what the locals had always known. Folks digging wells, canals, and aqueducts had long turned up walls and artifacts, all of which kept the memory of the towns from fading in the 1,700 years since they were buried. The stretch of farmland where Pompeii was eventually excavated had long been called ‘the City’ by the locals. An antiquarian writing 200 years earlier had even correctly associated the name of Herculaneum with its actual site. Nonetheless, it was useful to Charles to play himself up as a grand restorer of Neapolitan identity, so his propagandists pegged a recent unearthing of statues while digging a well as ‘the great rediscovery’.

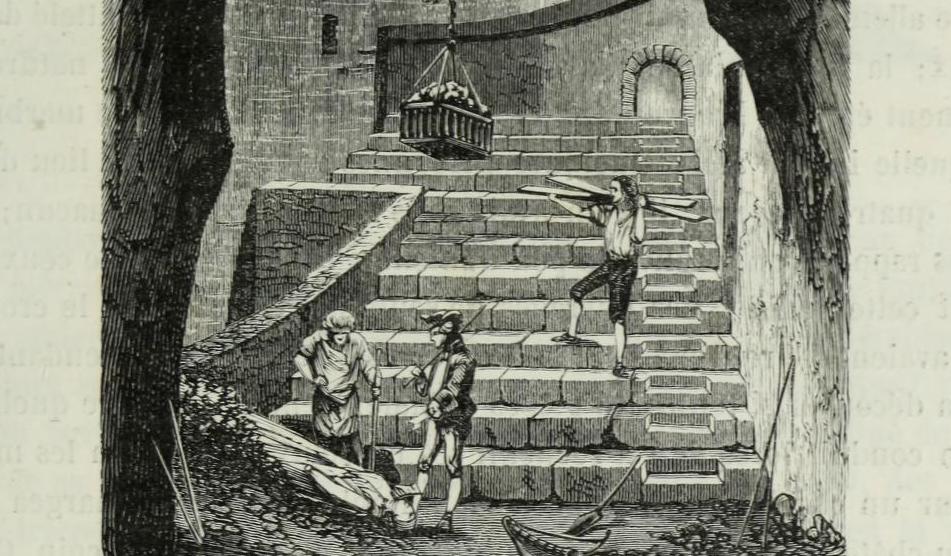

To dig up the treasures of Herculaneum, Charles appointed Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre, a military engineer and a captain in the Spanish army. Alcubierre would be the first to tell you he was no antiquarian. Though he admired the beauty of the stuff he excavated, he would later be described by contemporary Germany archaeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann as “having as little to do with antiquities as the moon does with a crayfish”. Alcubierre was a straightforward sort of soldier. He knew how to get things out of the ground: you build a mine. So he set about harvesting statues and frescoes the same way you’d harvest coal: sink a pit shaft until you hit the seam, then send tunnels out horizontally to follow the seam. The main difference was that this ‘seam’ was where the ancient surface had been 1,700 years prior, and Alcubierre’s miners were encountering the structures once built atop that ground, up to twenty meters below the modern surface.

This was no archaeological dig. Miners never saw a whole facade intact, never dug out around an object to see it in place. Their tunnels punched through ancient walls or ran along them. Larger objects had to be broken into pieces to bring them out. Cave-ins were a constant danger. Miners were killed by a mysterious gas that may have been pockets of carbon dioxide released when the miners broke through. The miners were prisoners of war; presumably Alcubierre couldn’t pay people enough to go down freely. Though their work was perilous, the miners were thorough. Their tunnels criss-crossed through entire buildings to map their edges and ensure no art was missed.

Alcubierre’s miners were not the first to ply the site. As they tunneled, the prisoners encountered other tunnels, so small the miners could barely squeeze inside. Later archaeologists dated pottery fragments in those tunnels to the 1600s, the 1500s, and the Middle Ages. Some may date all the way back to Roman antiquity. These earlier, anonymous treasure-miners seem to have mostly been after blocks of colored marble. One tunnel from the 1200s starts at the bottom of a well in the village above Herculaneum, then travels along an old Roman sidewalk. Where the tunnel went, the Medieval villagers pried up the marble pavement. Such slabs were in vogue at the time up on the surface; these guys probably made some decent money. That Herculaneum was not mined out until the 1700s suggests the villagers kept the source of their marble windfall a secret.

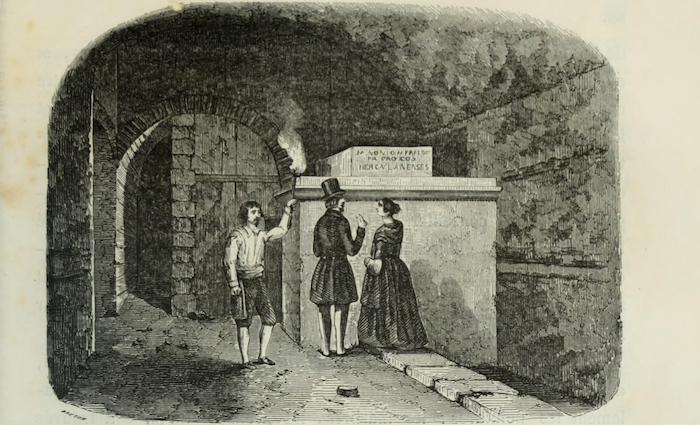

The political aims of Charles’ art mine were met for about the first ten years. For one, there was the simple fact of accumulating treasure. All these statues and frescoes and mosaics and objects d’art were valuable. Even if Charles never sold his treasures (and he didn’t), foreign courts knew he had this wealth and treated him differently. For another, there was tourism. Young, wealthy Europeans had long gone on the ‘Grand Tour’ where they traveled through Italy, marveling at her natural and cultural wonders. The work being done at Herculaneum moved the terminus of the Grand Tour to Naples. The sons of dukes and bankers visited Charles’ palace at Portici, where all the artwork was stored, and gawked at it. They descended into the tunnels to view the exposed walls. All this helped the court of Naples be perceived as its own entity, no longer seen as the mere appendage of some other, larger state.

But the Herculaneum art mine lost importance in the 1750s. First, resources and manpower shifted to Pompeii starting in 1748. While Herculaneum was buried under up to twenty meters of rock, Pompeii was under as little as four meters of softer ash and pumice. In 1750, the military engineer Alcubierre delegated the day-to-day work to his assistant, Karl Weber. Weber had long criticized the mine as unnecessarily destructive. He favored a more scientific methodology laid out by antiquarians – including John Aubrey, the Englishman who documented all those fun rumors I wrote four posts about in 2021 and early 2022. As early as 1747, Veronese antiquarian Scipione Maffei was urging the site be excavated from above, the way archaeologists usually do today. With Weber at the helm, these critics were heeded, the mine petered out, and it was eventually shut down.

This ‘Grand Tour’ business started to backfire. There wasn’t a museum; the treasures were in Charles VII’s palace. Not just anybody from out of town could be admitted to the palace. Many educated foreigners who lacked sufficient royal connections were forbidden access. They grated at this refusal. To them, the past was the shared heritage of all mankind. To Charles, the past of the Kingdom of Naples was the personal property of its present king to do with as he pleased. He even had frescoes destroyed if they couldn’t be stored in his palace, lest they wind up on the open market and make Charles’ treasures less unique. The German art historian I quoted earlier, Winckelmann, wrote an open letter excoriating the king for his bad treatment of the site and his ungentlemanly treatment of foreign guests. Controversy raged.

Charles VII could weather this bad press, but his successor couldn’t. In 1759, the King of Spain died. Charles abdicated the crown of Naples (and the crown of Sicily) and scooted off to Madrid to become King Charles III of Spain. Charles’ son Ferdinand was now king of Naples and Sicily, but he was only eight years old. (He’d grow up to be useless anyway; I wrote a post involving him in 2021.) Winckelmann first visited the site in 1758, while Charles was still king, but published his angry account in 1762, under the boy king Ferdinand. This new, weak court stopped excavation at Herculaneum to focus on the more productive, more scientific dig at Pompeii.

Setup: Queen Carlotta was in a bind. She needed money (or at least folks to believe she had money), and she needed her people to see her as a legitimate heir to the area’s ten thousand years of history so they’d stop describing her much-needed reforms as ‘betraying our heritage’. So she ordered an art mine be dug at a newly-discovered (sort of) site a few miles outside the capital. She’s had some pushback from other countries about how she’s handling it, but so far it’s nothing she can’t brush off. Then miners started disappearing. The remaining miners soon ran off, and nobody else will go down in the mine. Queen Carlotta asks the PCs to venture into her art mine, figure out what’s going on, and deal with the problem. This dungeon crawl will be an investigation first and foremost – dungeon-as-puzzle, my favorite kind – and the resolution may involve international diplomacy.

Situation: This site is old, and there have been small-scale art mining expeditions all through its history. Each successive empire to occupy the site has left its mark on the buried ruins. The Lemurians who built the original city were wiped out by a volcanic eruption – though the current empire claims descent from them. Then there were antediluvian snake-people who sought Lemurian art and bones to use in awful rituals. Then there were the wild men who first populated the area after the great flood, and sent enslaved dwarves to dig for treasure in the ruins. Then there were the elves who flourished after them and dug on the site too. Or, y’know, whatever succession of aesthetically-distinct cultures works for your campaign setting.

Many people have died in the buried town. Obviously, there’s a lot of Lemurian dead, both from the volcanic eruption and from natural causes in the decades before. There are dead snake-people who released a pocket of bad air and asphyxiated. There are dead enslaved dwarves who were worked to death by their beast-man masters. And there are dead elven second sons who knew more about books than tunneling and triggered cave-ins.

The paid laborers working in Queen Carlotta’s mine bumped into the tunnels these earlier miners left behind. They didn’t understand what they discovered, left no map of the tunnels (theirs or those that predate them), and cannot be found to guide the PCs.

A few days ago, the miners reached the Lemurian graveyard. They woke up one of Lemuria’s greatest sculptors, Rhan, who rose in a state of undeath. Rhan is livid that these miners are callously and thoughtlessly stripping his city of all its art – some of it his! He has woken other Lemurian artists from their graves to help him kidnap and devour miners. Some of those artists have started waking up the snake-people, dwarf, and elf dead in their own tunnels. Many of those are touchy about having been ‘buried’ (left to rot) in Lemurian ground, rather than laid to rest according to their own customs. Some are so angry they’ll lash out at anyone they encounter. Others are willing to talk, and just want to return to their eternal rest.

This situation gives us a random encounter table. While down in the mine, roll 2d20 every time the PCs pass down a tunnel between two points of interest:

Random encounters (2d20):

2-6: Snake-person ghost, inscrutable and alien

7-8: Snake-person ghost, angry

9: Dwarf ghost, angry

10-11: Dwarf ghost, bitter and fatalistic

12: Elf ghost, apathetic

13-14: Elf ghost, curious

15: Elf ghost, angry

16: Lemurian artist ghost, confused

17: Lemurian artist ghost, angry

18-21: Ghost appropriate for the tunnel you’re in (see below). Roll 1d6 for its emotional state. Lower is angrier, higher is friendlier.

22+: No encounter

Rather than doing a formal map, I would recommend generating this dungeon randomly as you go. It’s supposed to be confusing down here. When the treadmill crane lowers the PCs to the bottom of the pit shaft, they find one tunnel leading into the mine. That takes them to a well-excavated interior of a home with a barrel-vaulted roof, as depicted much earlier in this post, in that 1870 illustration with the tourists. In this room, the PCs find the remains of two tourists and a local guide, all torn to shreds. There is evidence of frostbite on the exposed wounds. Something cold must have done this. (Obviously, it was angry ghosts.)

Every room or point of interest, including this first one, has 1d6 tunnels branching out from it. There are four types of tunnels: modern, elven, dwarven/beastmen, and snake-people. All four types of tunnels look different. The modern ones look recent; there’s still rock dust on them. The elven ones are polished but poorly-supported. The dwarven ones are rough around the edges but structurally excellent. And the snake-people tunnels are so small the PCs just barely fit. Most tunnels coming out of a point of interest will be the same type as the kind of tunnel that the PCs went through to arrive here. So, for example, most of the tunnels in that first room are modern. But each tunnel has a one-in-three chance of being of a different type. That type is randomly determined. In other words, there are four different tunnel networks down here, but lots of places where the PCs can transfer between them. This method of dungeon generation doesn’t account for how some of these tunnels must necessarily cross at other points, but since this dungeon isn’t a mapping exercise, that’s a level of abstraction I’m comfortable with.

Each tunnel connects two points of interest. When you travel down a tunnel, roll 1d10 on the list below to see what point of interest you reach. Each point of interest might repeat or not, at your discretion. The focus of this dungeon is not on the rooms. The rooms just provide enough information so when the PCs encounter a ghost that isn’t angry in one of the tunnels, they can ask it useful questions. Those ghosts can provide more information, so the PCs can eventually figure out what happened. The purpose of this dungeon isn’t to clear it. It’s to determine what’s actually going on down here so that the PCs can get the Lemurian artist Rhan to put this undead situation to rest.

Rooms (1d10):

1: A pit shaft of the same type as the tunnel that the PCs took to get here. It’s mostly collapsed, or even intentionally filled in.

2: The tunnel runs along an ancient sidewalk. All the pavement has been pried up, leaving only chips of marble to hint at what was once here.

3: Half a statue. The top half has been removed with a cutting implement appropriate for the type of tunnel network it’s in. Modern: crudely broken with a pickaxe. Elf: Expertly severed with a chisel. Dwarf/beastman: hastily broken with a hammer. Snake-people: dribbled with acid.

4. An exposed wall. Much of its outside surface has been removed, implying there was once a fresco here.

5. An exposed floor. It’s rough and covered in chisel marks. There was once a mosaic here, and it’s been removed.

6: A beautiful mosaic of a mask (the first image in this post). If touched, it yells in Lemurian. That’s why no one’s removed it. The mosaic claims to have been created by Rhan, the greatest artist of the Lemurians, and it’s proud of that fact. It holds Rhan in high esteem and can tell the PCs all about him. It doesn’t know anything that happened after the city was buried.

7: A beautiful mosaic of a skull (see image above). The skull was a magical trap once. It sucked into it the first miner who touched it. The miner was appropriate to the network this point of interest is in (dwarf, elf, etc.) This used up the trap’s enchantment, so the mosaic is now safe to touch. The miner is still trapped inside the mosaic. They can see, hear, and speak. They’ve seen some of what’s happened down here and can infer more, but the isolation has driven them quite mad.

8: A domestic altar (see image above). The art objects in the altar are obviously valuable. A corpse of a modern miner lies on the floor before the altar, torn to pieces and partially frostbitten. If the PCs try to steal from the altar – or even look like they might do so – the ghost of the Lemurian artist who made the altar appears. She shouts in Lemurian, “How many times do I have to teach you future people the same lesson?” Then she attacks.

Image credit: L-BBE. Released under a CC BY 3.0 license.

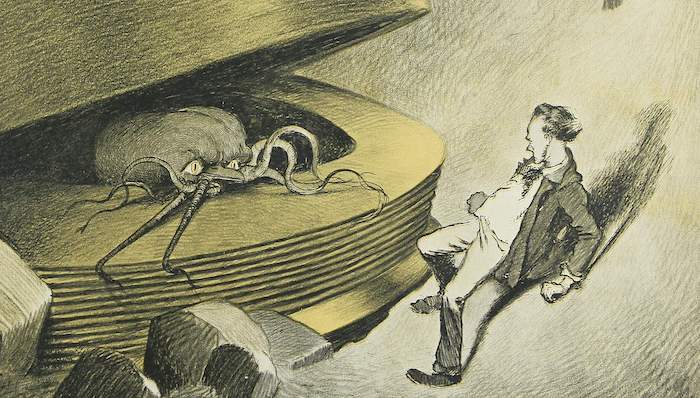

Before we get to room 9, a digression. Pompeii, Herculaneum’s sister city, is famous for the plaster casts of its corpses. During the volcanic eruption, people suffocating in the toxic gases laid down, passed out, and never got up. Their bodies were covered in feet of ash. Over months, their flesh decayed, leaving hollow voids in the ash where the body used to be – voids with skeletons inside them! Later excavators filled the voids with wet plaster which, when hardened, could be dug up to recreate the corpses where they lay. Some of these plaster molds even have teeth in the right place, which is eerie as hell. Herculaneum doesn’t have these corpse-voids. It was closer to the volcano and affected differently. There, people’s bodies were almost instantaneously superheated, vaporizing their flesh. People’s brains boiled in their heads and ruptured their skulls. Some charred skeletons survive in weird, gross poses. In the fantasy adventure, though, there are voids with skeletons inside them down in and around the art mine. The ghosts have woken up some of the skeletons, and the body-voids around the skeletons have also awoken. The skeletons now swim through the volcanic rock, suspended within moving body-voids. When one emerges from the tunnel wall, you see a skeletal hand reaching out of the stone – and around the arm bones is a gap, a tunnel in miniature, where the flesh once was!

9: The tunnel widens here. There are several partially-excavated body voids in the floor. You can see skeletons lying in them. If you walk up to the skeletons, a Lemurian ghost appears, wakes up the void-skeletons, and then disappears. The skeletons attack the PCs!

10: The tunnel widens and passes through the Lemurian graveyard. The ghost of Rhan, the greatest Lemurian artist and the cause of all this trouble, holds court here. He is attended by lots of void-skeletons. Some are standing near him, indistinguishable from regular skeletons. Others are half inside the rock wall. If the PCs don’t attack at first sight, Rhan is happy to talk. He’s upset about the art mine. He sees it as an insult to Lemuria and as outright grave-robbing. But he doesn’t want revenge. He’s not looking to press the attack on the surface world. He just wants the mining to stop.

While the PCs can stumble on room 10 ‘early’, don’t keep them from discovering it until it’s frustratingly late. If the PCs have figured out what’s going on down here, the next time you roll to see what room they encounter, fudge the roll. They encounter room 10 instead.

Outcome: Once the PCs have figured out the cause of this undead infestation, it’s up to them to do something about it. Killing Rhan will do it; the other ghosts and skeletons will gradually go back to sleep. But that’s a tough fight, and many groups won’t find it a satisfying ending.

Some groups may prefer to find a solution using diplomacy and compromise. Queen Carlotta will not give up her art collection. She needs the treasure, and she needs the historical legitimacy it gives her to pursue her reforms. Neither is she willing to tolerate an undead infestation only a few miles from her court. Her ideal solution is just to kill all the ghosts and skeletons again, then send in some priests to make sure they stay dead. But Queen Carlotta’s art mine has begun to attract complaints from foreign dignitaries who feel she’s handling the site badly. Clever PCs might be able to leverage that foreign pressure to extract concessions from Queen Carlotta: transition from exploitative, destructive mining to careful, scientific, and respectful archaeology. It’s not a concept the artist Rhan is familiar with, but when explained to him, he’ll find it an acceptable compromise.

Customization: The above is a skeletal (heh) framework. You’ll want to make it your own by customizing it to better fit your group. Reskin the Lemurians, snake-people, dwarves, beast-men, and elven second sons as groups relevant to your PCs. Got a tiefling in the group? Replace the snake-people with an empire of demon-worshippers, ideally the ones from whom the first tieflings sprang. Every time you introduce a new element of what’s going on in the art mine, you want at least one person at the table to say “Ooh, my character’s really interested in that.” Ditto the foreign pressure. If you’ve got an elf in the group, say that the foreigners complaining about Queen Carlotta’s handling of the site are an elf scholarly society that some of that character’s relatives are active in. And make Queen Carlotta relevant to your PCs’ interests too. Something about her personality, interests, or upbringing should reflect or clash with at least one member of the party.

Finally, don’t forget to customize the meat of this adventure to reflect the sorts of activities your players find fun. Are they really into combat? Revamp the random encounter table to add some encounters with void-skeletons. Don’t forget to make the void-skeletons different. Some were wizards in life and still have spells in death. Some were bruisers, or religious, etc, etc. You can even incorporate void-skeletons of animals like dogs and swine. Is your group more into roleplay? Add an enclave of miners down there who found a shrine that keeps the undead away and are sticking near it. Convincing them to come out (or just talking with them) can satisfy those players. And if your group is really into problem-solving, play up the politics. Maybe the different types of ghosts down in the mine are somehow connected to political factions on the surface. Make the diplomatic Gordian knot more complicated so your players feel cleverer when they solve it.

I put out a post based in real history or folklore every Tuesday! Make sure you don’t miss one by bookmarking MoltenSulfur.com or subscribing to get a no-frills email every week notifying you of the new post.

Sources:

Herculaneum: Past and Futureby Andrew Wallace-Hadrill (2011)

The Antiquarian Culture of Eighteenth-Century Naples as a Laboratory of New Ideas by Alain Schnapp (2013)

Pompeii versus Herculaneum by Eugene J. Dwyer (2013)