The Luddites were a British labor movement active roughly between 1811 and 1817. They opposed the growing mechanization of the British textile industry by smashing machines, burning buildings, and threatening – and sometimes killing – business leaders and magistrates. They had a secret, probably fictional, leader. And they’re more relevant now than ever. Let’s look at what drove these machine-breakers and how we can turn them into an adventure you can drop into your ongoing RPG campaign!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Robert Nichols. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Robert, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

The Luddites took their name from their ostensible leader, Ned Ludd, also called General Ludd, Captain Ludd, and even King Ludd. He probably never existed, but he was a useful rhetorical device. Threatening letters could be signed ‘Ned Ludd’. A little Ned Ludd mythology even sprung up, where he held court in Sherwood Forest like Robin Hood and had a ready army of thousands of sworn fighters. This shared mythology temporarily reframed machine-breaking – an established form of protest in Britain – into an anti-government, anti-industry movement that seemed to be (but probably wasn’t) nationally united. In their most active period, Luddite actions occurred nightly in some parts of the country, sometimes by groups as large as 300 people. The government took Luddism seriously and devoted considerable manpower to crushing it, even against the backdrop of the pressing needs of the Napoleonic Wars.

In truth, the Luddites seem to have been disaggregated and might not have had any sort of centralized organization – certainly not one controlling thousands of secret and sworn fighters. Most Luddites were professional textile workers. Before mechanization, they enjoyed decent wages and the respect of their peers. But new machines were changing all that.

– In the Midlands, Luddites opposed the use of the stocking frame: a kind of machine that makes knit fabrics quickly and inexpensively, but at lower quality. Thus, skilled Midlands hand-knitters were not only being put out of work by these machines, their own reputations as knitters were damaged by the inferior knit products being sold in stores.

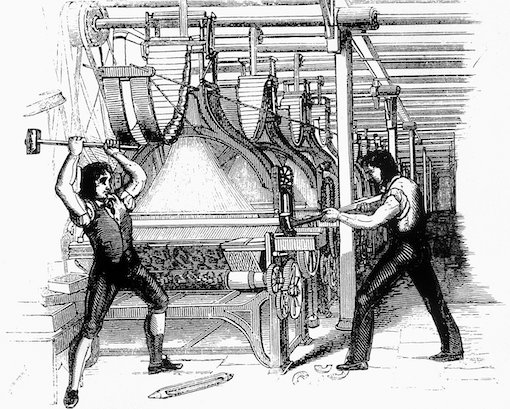

– In the northwest of England, around Manchester, Luddites objected to steam looms (also called power looms) that wove cotton cloth. Weaving on a steam loom required less skill than hand-weaving, so workers were easier to replace and could be paid lower wages in worse conditions.

– In the West Riding of Yorkshire, Luddites opposed shearing frames (which sheared the fuzz off woven wool more quickly but more poorly than could be done by hand) and gig mills (which teased the fuzz away from the surface of the cloth so it could be sheared more easily).

Image credit: Clem Rutter, Rochester, Kent. (www.clemrutter.net). Released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

The primary means Luddites used to fight the rise of these machines was to smash them with hammers. At least in Yorkshire, such hammers were often affectionally named ‘Enoch’. Luddites also burned mills and shops where machines were used, and burned the homes of mill and shop owners. But one of their most familiar methods was the anonymous threatening letter. Because Ned Ludd wasn’t real (or if he was, he was just some dude, not the all-powerful King Ludd), anyone could pen a letter and sign it ‘General Ludd’. Like the endless anonymous death threats American members of congress receive today, most of these threats were vacuous. But some weren’t, and that made it hard to decide how to react to any individual letter. What follows is my favorite letter, which was posted publicly in Nottingham in November, 1811. I’ve modernized the proclamation to improve readability.

Declaration: Extraordinary

Justice

Death or Revenge

To our well-beloved brother and Captain-in-Chief, Edward Ludd.

Whereas it hath been represented to us, the general agitators for the northern counties, assembled to redress the grievances of the operative mechanics, that:

– Charles Lacy of Nottingham, the lace manufacturer, has been guilty of diverse fraudulent and oppressive acts.

– He has reduced to poverty and misery 700 of our beloved brethren.

– By making fraudulent cotton-point net of one-thread stuff, he has made £15,000 and ruined both the cotton-lace trade and our worthy and well-beloved brethren, whose support and comfort depended on the continuance of that manufacture.

It appeareth to us that Charles Lacy had the most diabolical motives: to get rich by the misery of his fellow creatures. To make an example of him, we therefore do adjudge his £15,000 to be forfeit. And we do hereby authorize, empower, and enjoin you to command Charles Lacy to disburse the sum within ten days to the workmen who made cotton net in the year 1807.

If he doesn’t, we do command you to inflict the punishment of Death on Charles Lacy, and we do authorize the payment of £50 to anyone employed for that purpose. We enjoin you to present this order to Charles Lacy without delay.

The Luddites were mostly able to get away with their direct action because they were popular. In some cases, authorities couldn’t find anyone who didn’t support Luddite actions – even the owners of the buildings in which the machines were housed were Luddite sympathizers. That’s partially because the same forces that were hurting textile workers were also hurting just about everyone else. Most farmers earned at least some money spinning thread; it was work you could do at night or in the long winter. The spread of a machine called the spinning jenny took that income away. Furthermore, increased demand for wool made the raising of sheep more profitable, which drove up rents on small farms. Many tenant farmers were priced out, and the great British landlords replaced them with sheep. This trend was most dramatic in the Highland Clearances of 1750-1860. Displaced people poured into the cities, where they found insufficient jobs, insufficient wages, and ever-growing slums. Suffice to say that few ordinary Britons were particularly sympathetic to the textile factories that William Blake so memorably termed “dark, Satanic mills”.

Things never got better for the Luddites. Their machine-smashing, arson, occasional assassinations, and mill-burning failed to stop the mechanization of textile work. Decades later, jobs arose to replace the good jobs that were lost, but not in the lifetimes of the people hurt by industrialization. They never got back anything resembling the pay and respect they enjoyed in their old jobs. All the rest of the British public got in exchange was cheaper clothing made of worse fabric and more competition for jobs. In the 20th century, automation and industrialization generally created new, better jobs as fast as it destroyed older, backbreaking jobs. We’ve come to take this process for granted – of course automation makes everyone’s lives better. But the benefits brought by automation aren’t a universal, guaranteed phenomenon. The Luddites showed us that.

I’ve long been terrified about machines replacing cashiers, shelf-stockers, and fast food workers – jobs often done by vulnerable people who don’t have many other options for employment. What will happen to them when those jobs are largely gone? The example of the Luddites suggests that – unless we make some surprising policy changes – many will squeeze more and more roommates into ever-smaller shared apartments and die decades before their time. Now with AI art, the Luddites’ warning has arrived in the RPG space, bringing worse but cheaper art, just as the stocking frames delivered worse but cheaper knit fabrics. The stocking frames proved unstoppable. I suspect AI art may be as well.

Image Credit: Clem Rutter, Rochester, Kent. (www.clemrutter.net). Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Anyway, this is supposed to be a history blog with RPG content, not a despair blog full of confusion. So how about an adventure idea?

If you’re going to use a fictional movement inspired by the Luddites in your ongoing RPG campaign, your first task is to decide what they’re reacting to. In science fiction, this is easy. A task that was long thought un-automatable has suddenly become automated on one particular planet. Make sure the task is tied to something iconic in your campaign setting. In Star Wars, maybe it’s harvesting Khyber crystals for lightsabers. In Star Trek, it’s making the miniature black holes that power Romulan vessels. In a modern-ish setting, use an impending technology people are already anxious about and will replace a lot of workers: self-driving semi-trucks, burger-flipping machines, or grocery store shelf restocking robots. In fantasy, this is a little harder. In pre-modern settings where people do the work of machines, Luddite anxieties are anti-immigrant anxieties, and that’s a whole different thing. But if there’s a little magi-tech in your setting, you can have hired farmhands being put out of work in this region by the cheap, shoddy automatons being built by that artificer in the tower over there.

When the PCs land at the spaceport or stroll into town, they see a flier posted in the style of the ‘Declaration: Extraordinary’ proclamation. Just copy-paste that, change a few details, print it out, and pass it out as a handout at the table. Particularly murder-hobo-y parties may see the £50 bounty and proceed straight to that dude’s house to kill him. But I like to think that most parties will read the proclamation and say, “Hm. That’s troubling.”

Then the party is approached by the local authorities. The mayor explains that all the trouble is the fault of this ‘Ned Ludd’ character (obviously change the name – and the name of the movement). There were never any problems before Ned Ludd showed up. Could they find and arrest Ned Ludd for her? The mayor’s not lying. She doesn’t know there is no Ned Ludd, and she’s unable to recognize that Ned Ludd and the unrest are both symptoms of changing labor conditions. The party is decently likely to seek out Ned Ludd, whether to arrest him for the mayor, join him in the struggle, or just get some answers.

Then let the setting respond to however the party goes about finding Ned Ludd. If they give the impression they’re trying to bring him in, the Luddites get wind of this. A gang of Luddites with hammers named ‘Enoch’ shows up on the PCs’ doorstep to ‘talk’. In their pockets are multiple letters and pieces of propaganda signed ‘Ned Ludd’, all in different handwriting. If the PCs give the impression they’re looking to join the Luddites, the cops show up to try to take the PCs in for ‘questioning’, and the mayor is livid. You want the adventure to feel unique and special, though – particular to your group and your setting – so devise in advance some other ways your setting might respond to your particular PCs poking their noses where they don’t belong. Then keep playing these reactions until the players realize that there really is no Ned Ludd, no organized Luddite militia, and no secret conspiracy. There’s just a bunch of pissed-off workers who see only a bad future ahead of them.

This realization gives the PCs a really fun trigger to roleplay to. There’s no money to be earned. There’s not even a win condition. There’s no way to decapitate the Luddite movement. And even if you can convince the mayor to outlaw the technology that gave rise to the movement (unlikely), that machine is still going to spread to other areas. Eventually it’ll circle back here too; it’s just a matter of time. So when presented with a no-win situation, how do the PCs respond?

Finally – and this is very important – immediately give the PCs something easy they can accomplish. Maybe a Luddite they’ve befriended was kidnapped by goblins (totally unrelated to the Luddite thing), so the PCs can go beat up some goblins to get her back. Maybe the mayor found a treasure vault under her mansion, but it’s guarded by a puzzle lock. Solving this easy task won’t solve the Luddite conundrum, but it does mean the PCs get to end with a win. No-win situations in games rub a lot of players the wrong way. For folks who game to escape the grinding string of no-win situations that make up their daily lives, a GM intentionally throwing a no-win situation at them in-game is a serious bummer – almost a betrayal. Make sure you don’t time this adventure such that the players go home immediately after realizing there’s nothing they can do. Give them the opportunity to do some meaningful roleplay, then give them an easy win so they’re smiling on their drive home. They got to eat the rich, bitter roasted Brussels sprouts of roleplayed disappointment and they still got a slice of sweet, empty cake for dessert.

Check out my book Making History: Three One-Session RPGs! It’s three awesome historical one-shots with pregenerated characters and a very simple rules system designed specifically for that story. Norse Ivory is a game about heritage and faith in the Viking Age. A Killing in Cahokia is a murder mystery in the Native American temple-city of Cahokia. And Darken Ship is a horror-adventure starring junior sailors on a U.S. Navy warship who wake up one morning to discover they’re alone on a ship that should carry three thousand.

Source: Writings of the Luddites, edited by Kevin Binfield (2004)