This week we return to another intriguing moment in the autobiography of Babur (1483-1530). He would go on to found the Mughal Empire in India, but at this point in his story he was mid-career: king of Kabul with his eyes on the stars. This post is going to be about a manhunt! It’s got some really interesting political context, but at its heart, it’s Babur chasing a mirror-universe version of himself through the hills of Punjab! It’s a really cool template for an RPG adventure.

This is the fourth post in this monthly Babur series.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

When last we left Babur, he was king of Kabul with no chance of returning to his homeland in Uzbekistan. Powerful nations lay north and west of him, and a desert lay to the south. He spent the next 16 years campaigning continuously: raiding the Delhi Sultanate to the east, putting down rebellions in Afghanistan, and riding into the hills to build pyramids of heads when the mountain tribes acted up. His actions didn’t amount to much. But in 1523, when Babur was 40, all that would change.

The Delhi Sultanate was 300 years old. At its height, it controlled almost all of what is today India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. By Babur’s day, the sultanate was a cultural and economic backwater governing a stretch of northern India and northern Pakistan. The ruling Lodi dynasty was falling apart. The emperor, Ibrahim Lodi, was arrogant, greedy, and paranoid. His nobles didn’t trust him, and the summary executions he used to bring them into line didn’t do much to engender devotion or loyalty. One noble in particular was certain he was slated for execution: Daulat Khan Lodi, the governor of Lahore. Daulat Khan’s territory (the Punjab) wasn’t far from Babur’s kingdom. So Daulat Khan invited Babur to bring his army to Lahore and the Punjab.

Babur had taken his army into the Delhi Sultanate before, but this time was different. His earlier expeditions were large-scale raids: opportunities for his soldiers to steal sheep, earn status, and have a reasons to stay loyal to Babur. This time, he’d be supported by the governor and his troops. Babur would have no reason to withdraw when the fighting season was done. This time, Babur could stay.

Babur won Daulat Khan’s war for him. An army from Delhi – not knowing Babur was on his way – had marched on Lahore to subdue the rebellious governor. Babur smashed it. He let his troops sack Lahore, then took several other cities in the Punjab, killing everyone inside one of them.

This is a different Babur from the one we met in previous posts. Remember when a teenage Babur opted to punish his soldiers when they’d robbed the people under their protection, even though he desperately needed those soldiers’ support? Remember how those soldiers turned on him and cost him his kingship? This is a much older Babur, and he’s not going to make the same mistake again. If doing evil is what it takes to win, this Babur will do it. In his personal affairs, he still demonstrates remarkable qualities of mercy, curiosity, and humor. But in his dealings with soldiers and commoners, he’s brutal.

We also can’t overlook the religious aspect. In Central Asia, Babur was fighting other Muslims. Many Punjabis in the 1500s were Muslims, especially among the ruling class. But a lot of ordinary Punjabis were Hindus and early Sikhs. That mattered to Babur. I’m not endorsing the narrative about him that’s popular in India’s ruling Hindu nationalist BJP party. To the BJP, Babur was a fanatic and self-appointed scourge of the unbelievers: a convenient boogeyman to justify anti-Muslim rhetoric. That’s just not so. But we can’t deny that Babur’s own words show him to be much more willing to commit atrocities against those who didn’t share his religion.

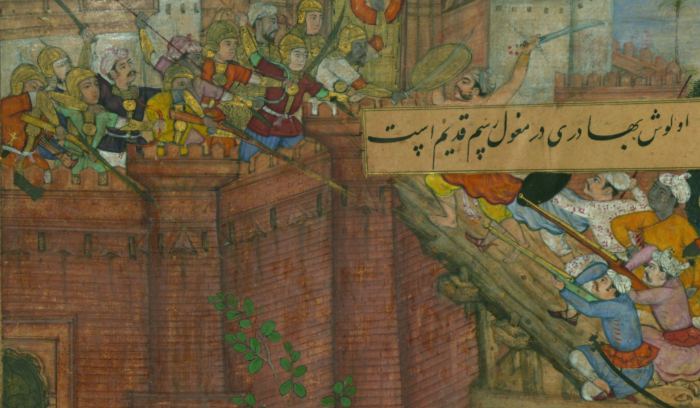

Things didn’t work out as Daulat Khan had planned. Babur integrated the Punjab into his kingdom. He placed garrisons in the cities and assigned governorships to loyal followers. Daulat Khan thought he’d be assigned Lahore, his former seat and the finest city of the lot. Instead, Daulat Khan got a less-important city. Babur returned to Kabul and Daulat Khan raised an army to take the Punjab for himself. So Babur came back. He trapped Daulat Khan in a fortress. After a siege, Daulat Khan surrendered.

This is where we introduce the real subject of this post: Daulat Khan’s son Ghazi Khan Lodi. Daulat Khan was an old man. He’d actually die of old age just weeks after this incident. His son Ghazi Khan was the intended beneficiary of all these rebellions. He’d be the one to inherit Lahore. (Daulat Khan had another son, but he’d betrayed his father and brother and joined Babur, so that guy was probably out of the will.) Ghazi Khan was in the fortress with his father when the siege started. It was very important that Babur capture Ghazi Khan, as a rogue princeling with claims to legitimacy can cause no end of trouble. Babur knew this better than most since that was his own origin story. Remember Shaybani, the Uzbek king who drove Babur stateless through the mountains to the court of a more-powerful relative? Now Babur was Shaybani, chasing a younger version of himself.

First, Babur sent people to search the fort. Ghazi Khan’s father told Babur that Ghazi had fled into the hills. But some others (Babur does not record who) reported seeing Ghazi Khan inside the fortress after he’d supposedly fled. So Babur posted guards at the gate to keep the young man from leaving – and to curtail the quiet departure of Daulat Khan’s gold and jewels. Soldiers checking the fortress didn’t find Ghazi Khan, but they did find his library. It was a mixed bag. There were many notable books on learned topics, but few were valuable. Babur might have hoped to find books with bejeweled covers and gorgeous calligraphy that he could distribute as precious gifts. Instead, he found mostly workmanlike copies intended to be read rather than admired. All this searching did turn up Ghazi Khan’s family, but not the man himself. He must truly have fled.

So Babur sent two officers and a troop of soldiers into the hills. This force found no definite news of Ghazi Khan but did scout out some forts. One, named Kutila, had been strengthened by Ghazi Khan personally in the years preceding and was well-garrisoned. It seemed the likeliest place he might be. Kutila was built on a fin of rock jutting out over a precipice. The vertical drop on three sides was 70 or 80 yards. Entering the fort required crossing a drawbridge. The original language is ambiguous as to the particulars, but it might be that where the fin connected to the ‘mainland’, it had been dug out to a depth of 7 or 8 yards to create an island in the sky.

Babur’s Ghazi-Khan-chasing detachment assaulted Kutila all day. They had almost taken it when night fell and they withdrew. That night, the fort’s garrison escaped. Presumably they lowered themselves on ropes down the backside of the the fort. If so, the bottom of the precipice was probably unguarded. Getting down there could have taken the attackers hours, and all hands were probably needed during the day to assault the fort. In the morning, the detachment chased after the fort’s garrison, presumably still ignorant of whether Ghazi Khan was actually among them.

At this point, Ghazi Khan disappears from Babur’s autobiography. We can get a little more from the Indo-Persian historian Firishta, who tells us that Ghazi Khan was overtaken, defeated, got away, and was pursued very closely all the way to Delhi. There he joined up with Emperor Ibrahim Lodi. Then Ghazi Khan vanishes from Firishta too. We might wonder whether Emperor Ibrahim pardoned Ghazi. It seems out of character for the emperor, but if he’d had the rebellious princeling executed, wouldn’t Firishta have mentioned it? If Ghazi was lucky enough to get a pardon, he probably fought in Ibrahim’s army when the emperor fought Babur later that year. If so, it probably didn’t go well for him. Babur’s much smaller army, armed with matchlocks and mortars, decisively defeated Emperor Ibrahim, who died in the battle, Babur took Delhi, and the Delhi Sultanate was absorbed into Babur’s Kabul-based state – which we now call the Mughal Empire.

At your table, you might have your party roll up on a city or fortress just after another nation seizes it. The real soldiers are busy with soldier business, so the party gets hired to chase down a princeling or government official who should have been in the city but hasn’t been found. Some people say they saw him fleeing for the hills (or the asteroid belt or whatever), while others swear they saw him in the government complex today. Searching the government complex turns up three clues as to his whereabouts. The first is his spouse, who can be convinced to reveal that he fled to his private fortress. The second is a reliable witness who saw him leave. In science-fiction, maybe it’s a law robot. In modern-day it’s someone with cell phone footage. In fantasy, it’s an honorable knight. The third clue is a map and blueprint in his private library.

I know it’s cliché, but it really is a good idea to have three clues to something you don’t want your players to miss. They’ll overlook the first and misinterpret the second, but the third will definitely get them. Also, don’t sleep on the private library. It’s a great way to help your players get to know the guy they’re chasing. His choice of books, which ones seem heavily read, what notes he made in the margins – all this stuff is useful. If you want to lean into the idea that the fugitive is a sort of mirror-universe twin of the PCs’ employer, this is where you reveal it.

So the party chases this guy into the hills, where they find the fortress he personally overhauled. Makes sense that he’s in there, right? Particularly suspicious PCs might have to find a way to verify his presence. Forward-thinking PCs will want to look for secret exits. Assaulting the fort can probably be skimmed over with a few lines of narration. If you’re trying to make this an adventure about pursuit and investigation, a big battle in the middle is just a distraction. In any case, the fugitive tries to make an escape. Maybe he succeeds, maybe he doesn’t.

The party can still try to catch him while he’s on the run to your Delhi-analogue. If the PCs fail then too, they can still enter Delhi and try to convince whoever Ghazi Khan has fled to that he shouldn’t pardon Ghazi, but should instead hand him back over. But be careful: the real Ibrahim Lodi sometimes imprisoned messengers from his enemies. And of course when the party is transporting the fugitive back to their employer, he’ll try to convince them to change sides. This is the payoff for them getting to know him back in his library – now they get to talk to him.

The serial nature of this style of adventure design presents a fun mathematical opportunity. You can make each of these challenges difficult – much harder than feels fair. Because if the PCs don’t catch this guy at the first opportunity, no worries. They’ll get more chances to catch him. Let’s say you present four opportunities for the PCs to grab this guy: in the fort, while escaping the fort, on the road to Delhi, and in Delhi. If you give them only a 33% chance of success each time, the odds that they’ll succeed on at least one of them are actually 80%! Or you can make it likelier that the party will get to play through all four obstacles by giving the first one a 20% chance of success, the second and third 30% chances, and the fourth a 50% chance of success. It still comes out to 80% odds that they’ll get the guy! This is something we as RPG gamers understand intuitively. If you roll a lot of dice, at least one of them will produce an unusual result, right? This structure of adventure takes advantage of that fact to produce situations that feel really challenging (even unfair), but will still likely be won by the players.

Check out Shanty Hunters, my award-winning TTRPG about collecting magical sea shanties in the year 1880, then singing them at the table with your friends. The lyrics of the shanties come to life and cause problems for you and for the crew of the ship you sail aboard. It’s up to you to find clues in the song and put things right!