The unexpected murder of the Roman emperor Caligula in 41 A.D. is a great template for a political catastrophe the PCs can turn to their gain. In the chaos after the assassination, a small band armed with a plausible candidate, sweet tongues, and sharp swords could ram through their selection for the next emperor. It works the same for a chieftain, space admiral, or mob boss.

The madness and abuses of the emperor Caligula are legendary. He ordered the massacre of a stadium full of people asking for lower taxes. He made himself the equal of the head god Jupiter. Most famously, he tried to make his favorite horse a government official. The historian Josephus accuses him of “ten thousand mischiefs”. Now, there’s plenty of room to debate whether these abuses actually occurred, but there’s one man who’d had enough: Chaerea, one of Caligula’s bodyguards, torturers, and agents, whom Caligula teased viciously for supposedly being effeminate. Four years into Caligula’s reign, Chaerea snapped.

Chaerea was a member of the Praetorian Guard, a legion of crack troops stationed in Rome. The Guard was the only legion not posted to the borders of the empire. Their job was to protect the emperor. Over the centuries, the Praetorian Guard would develop a long reputation for assassinating emperors they didn’t like and selecting emperors they preferred, but 41 A.D. was only the first time they did so.

In January, Chaerea and a few friends hacked Caligula to death in a private corridor in the palace. They split up and got away.

This is where the adventure begins in an RPG context! It doesn’t matter whether the fictional ruler in your campaign was mad or just, and it doesn’t matter who killed her. What matters is that she’s dead, and what happens next. The chain of events following the assassination of Caligula is a good default for what happens if the PCs don’t get involved. It’s got a variety of plots, movers, and shakers, all bouncing off one another. Inject your PCs into the mix, and things might go very differently!

Image credit: Louis le Grand, released under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

This is a great place to mention that the Roman empire didn’t have an established system of succession. The medieval European system of primogeniture (everything passing to the firstborn son) did not exist. You might have been taught that Roman emperors adopted their successors, but that really only happened for emperors who didn’t have blood descendants.

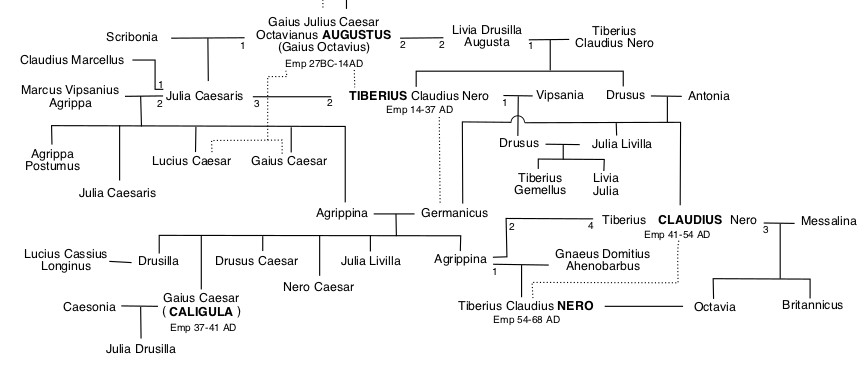

Caligula was a descendant of Augustus (Julius Caesar’s adoptive successor). His predecessors generally tried to keep succession unambiguous by adopting their most promising-looking descendants (moving them up a rung or two on the family tree) and arranging marriages between their close relatives. But these relatives and descendants had an unfortunate habit of dying young, leaving their spouses to remarry other family members and have still more children. Caligula’s family tree is an unholy, eight-dimensional mess of children who are their own grandfathers and uncles to their own half-brothers.

And then Caligula died suddenly without a son, adoptive or otherwise. Anyone with a credible claim to being closely related to him and a strong political backing could wind up emperor.

Image credit: Rursus. Released under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

The immediate result of Caligula’s murder was violence. The Praetorian Guard was Caligula’s personal bodyguard unit, but he had a second, smaller, even more personal bodyguard of German mercenaries loyal only to him. When the Germans discovered Caligula’s body, they went on a rampage through the palace. They were theoretically targeting folks who might be connected to the murder, but the result was a lot of dead senators and no dead Chaerea.

When the Roman Senate got wind of Caligula’s death, the senators met in the Temple of Jupiter. The Senate hadn’t had much real power for almost a hundred years, since Julius Caesar seized power and ended the Roman Republic. Now the senators had a shot at reclaiming their power. One senator, Gnaeus Sentius Saturninus stood up and gave a rousing speech about reclaiming liberty from tyranny. Of course, none of these men had ever seen a world without an emperor, and may not have even understood what such a world entailed – even as he spoke, Saturninus was wearing a signet ring with Caligula’s face on it.

Four regiments of the Praetorian Guard, led by Chaerea, promised their support to the Senate. Chaerea’s first order of business was sending someone to kill Caligula’s wife and infant daughter. This assassin found Caligula’s wife and daughter weeping beside his body in the palace and smeared with his blood. Caligula’s wife presented her neck boldly, and she and her daughter died beside the late emperor.

But the majority of the Praetorian Guard preferred that the empire continue. They went looking for an emperor. The Praetorians found Caligula’s uncle, a man named Claudius, hiding in an alley. Claudius thought the soldiers were going to kill him, but instead they dragged him to his feet and proclaimed him emperor. They carried him in a sedan chair to their camp and asked that, later in his rule, Claudius remember the men who had been so generous to him. Claudius, it seems, wanted no part of any of this. But surrounded by an army of armed men, he didn’t have much choice.

When the Senate heard the Praetorians had declared Claudius emperor, two senators went to Claudius to implore him to give up power and let the Senate rule the Roman Empire. They argued that the rule of one man over all was tyranny, and that only the Senate could govern justly. The speech didn’t go over well. Fearing for their lives, the two senators reversed course. They assured Claudius that as long as he didn’t want the throne, he should take it and consider it a gift from the Senate.

At this point, the King of the Jews enters the scene. No, not that King of the Jews, but Herod Agrippa, the Roman-installed client king of Judea, and the grandson of the King Herod from the Bible. King Herod Agrippa was an old friend of Claudius’. They’d grown up together in Rome. During the assassination, Agrippa was back in Rome on other business. Sources differ, but it looks like Agrippa encouraged Claudius to accept the Senate’s hasty offer – and to order the Praetorian forces arrayed for and against the Senate not to fight. Agrippa served as an intermediary, traveling between the two camps. Through his hasty intervention, further violence was averted.

Even during Agrippa’s midnight negotiations, some senators were quietly putting their own names forward as candidates to succeed Caligula as emperor. None gained support as a consensus candidate, and they fled the city.

By dawn the morning after the assassination, those Praetorians who had supported the Senate left to join Claudius’ faction. The remaining senators went one by one to Claudius to swear loyalty. Chaerea also tried to join the pro-Claudius faction. But Claudius’ advisors convinced him to order Chaerea killed, arguing that the death of Caligula was good, but perfidy by the soldiery must still be punished. Claudius also paid each member of the Praetorian Guard a huge sum as ‘thanks’ for their ‘loyalty’ to him.

In an adventure based on Claudius’ ascent to the throne, there are lots of places for the PCs to insert themselves (though obviously you’ll need to change the details to fit your fictional setting):

– Stopping the rampaging Germans, and thereby gaining credibility with the people and the Senate

– Breaking up the meeting of the Senate at the temple of Jupiter

– Finding another member of Caligula’s family to proclaim as emperor (for instance, Marcus Vinicius, Caligula’s brother-in-law)

– Saving Caligula’s family and declaring themselves regents for his baby daughter, the new empress

– Finding Claudius before the Praetorians, and hiding him or proclaiming him emperor before they can

– Replacing the Senate’s envoy to Claudius and giving a better speech

– Smuggling Claudius out of the Praetorians’ camp so the Guard has to rally around the party’s candidate

– Influencing King Herod Agrippa’s counsel to Claudius

– Burning the treasury so Claudius can’t buy the long-term loyalty of the Praetorians

Obviously, this is an adventure that will require a lot of improvisation. But if you stat up the relevant parties ahead of time and keep track of what the Praetorians, the Senate, the Germans, and King Herod Agrippa are doing while the PCs are elsewhere, this could be a lot of fun. If the PCs can pull off placing their own candidate upon the throne, they’ll likely find the deeply grateful emperor willing to do whatever they want.

There’s one neat coda to this story relevant to the PCs: Caligula’s legacy. Most of the sources we have for Caligula’s madness and abuses date to well after his reign. It’s certainly possible Claudius did his best to spread rumors sullying the memory of his predecessor. After all, Claudius’ legitimacy rested in no small part on the idea that Caligula’s death was justified. A few stories here and there about a massacre or a horse would certainly help. Whoever winds up on the throne in your campaign, your PCs might want to spread a little slander about your version of Caligula themselves.

–

Sources:

SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome by Mary Beard

Antiquities of the Jews by Titus Flavius Josephus