In 1815, Mount Tambora in modern-day Indonesia erupted catastrophically. The ash and gasses it released reduced temperatures in some distant parts of the world so much that 1816 has come to be called ‘The Year Without a Summer’. It was an agricultural disaster, and the follow-on effects of the famines had a non-trivial impact on the course of history. The Year Without a Summer is a fantastic template for an ‘epic-tier’ threat in RPGs – something that high-level fantasy, superhero, or science fiction characters can reckon with and try to combat.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

In 1812, Mt. Tambora on the island of Sumbawa, in the Indonesian archipelago (at the time the Dutch East Indies) started smoking. This came as a surprise to the good people of Sumbawa, who did not know Mt. Tambora was a volcano. On April 5th, 1815, it began erupting properly. The ash cloud was carried upward on its own heat like smoke up a chimney, and shot straight into the stratosphere. On April 10th, the mountain erupted again. This time, ash, poison gas, and great blocks of pumice exploded outwards, destroying all towns within 20 kilometers. The former Dutch governor of Java recorded eyewitness accounts of people lighting candles at midday and of confusing the far-off explosions for cannon fire and mustering the militia. Those closer to the eruption did not live to describe it. Tens of thousands were killed immediately by whirlwinds of hot dust and ash. Tens of thousands more died of famine and disease in the months that followed. The island’s population of 180,000 was cut in half. The Mt. Tambora eruptions of 1815 remain the deadliest volcanic event in human history.

This was a colossal eruption. Measured by the amount of thermal energy released, it was 100 times larger than the eruption of Mt. St. Helens. Besides the ash, the event released millions of tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. There, it formed aerosolized sulfuric acid, which coagulated into a sort of dust. The dust was so high up, it sat above the weather and did not precipitate out as acid rain. Instead, it stuck around. While the heavier ash rained down around the world, the sulfuric acid dust formed a veil over the planet that reflected sunlight back into space. The whole planet simply received less heat. This altered global weather systems. Because of the vagaries of these systems, most of the world saw no change. But Europe, New England, and eastern Canada suffered unseasonably cold conditions. Averaged across the world, 1816 was probably only half a degree Celsius colder, but in the affected regions that was more like three or four degrees. That was enough to devastate harvests.

It couldn’t have come at a worse time. This was a Europe already reeling from the Napoleonic Wars. The Battle of Waterloo was in 1815 – after the eruption of Mt. Tambora, but before the weather effects were felt. By 1816, there was no work to be had. The munitions factories were shuttered, and hadn’t been converted to produce household goods. International trade was only beginning to restart. It was a bad time for the weather to turn.

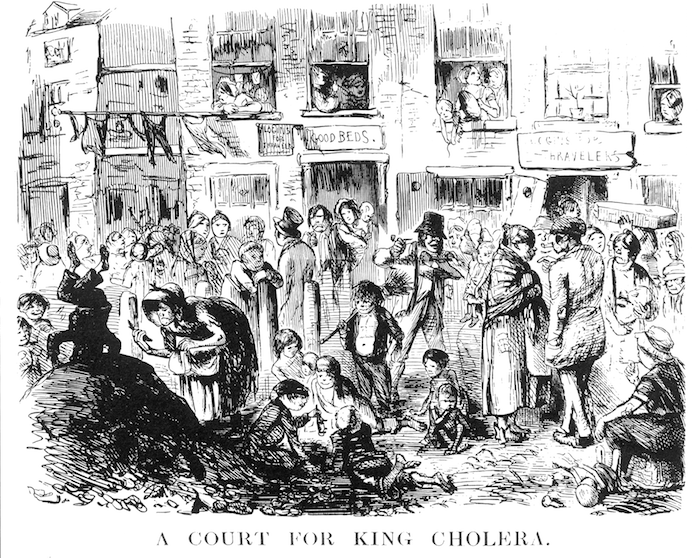

The spring of 1816 was cold and rainy. Frosts struck in June, July, and August. Orange and brown snow fell in central Europe in June. Thunderstorms wracked the continent, flooding fields and cities. Black clouds blotted out the sun. Harvests failed. Poor yields continued through 1817 and 1818. Areas that could imported grain from the American Midwest (which was spared). In areas that couldn’t, people starved. A prophecy by a Bolognese astronomer predicted the end of the world. There were bread riots across Europe – not just in the cities, but also in the countryside. Political radicalism began to spread. In Britain, calls grew for universal male suffrage. The government pushed back violently, most famously at the Peterloo Massacre. And as always during famine and chaos, epidemics sprang up all over the affected areas.

Paradoxically, it’s harder for scientists to connect the Tambora eruption to disasters in Asia. The peculiarities of global weather systems make it unclear whether odd weather in Asia at the time can be causally linked to Tambora. Nonetheless, two events occured that raise suspicions. First, cold weather devastated harvests in Yunan Province, China, three years in a row. The Imperial government had a sophisticated system for reallocating food surpluses elsewhere in the country to mitigate famine, but the severity of the situation in Yunan overwhelmed the system. When good weather eventually returned, the cash-strapped survivors planted not rice but opium. In India, epidemics permitted cholera to evolve into a dangerous new strain that was able to leave the subcontinent for the first time. Cholera pandemics over the next century would kill millions.

On Sumbawa, there were lingering effects. Many survivors emigrated to other islands. Some had to sell their children as slaves to afford food. The Sultan of the island imported other slaves to replace his lost peasants, but agriculture was only possible in the highlands. Every year, rains washed ash down into the lowlands, creating mudflows and destroying anything built down there. The island’s demography still shows the signs of all this resettlement.

In the West, the Year Without a Summer drove a heightened period of emigration from Europe to the United States – and of westward travel within the United States, since the Midwest (which was then the frontier) wasn’t affected. These population movements led directly to the concentration of religious idealists and utopianists in western New York state and eastern Ohio. This region later came to be called ‘the burned-over district’ for the series of religious revivals that blazed across it. It became the heartland of the abolitionist movement and the women’s suffrage movement in the 19th century and the origin site of the Mormon Church.

The Year Without a Summer also had a brief but noticeable effect on Western artists. Landscapes painted that year were noticeably redder, from the ash that still colored the sky. Mary Shelly was trapped indoors by unseasonable weather and consequently wrote Frankenstein. Her traveling companion, Lord Byron, was inspired to write the poem Darkness (“The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars/Did wander darkling in the eternal space”).

You can drop The Year Without a Summer into any fictional RPG setting that has volcanoes. In a science fiction or superhero game, the year functions best as a threat. There’s a catastrophic eruption somewhere and volcanologists say it’s probably going to keep erupting for months. Scientists immediately raise the alarm about a repeat of 1816. The PCs have to find a way to stop the ongoing eruption. As they do that, they find evidence that all is not as it seems, that some sinister agent has triggered the eruption for her own purposes. Can the PCs stop her in time? This scenario works well as a climate change parable, because people won’t die immediately. But by the time the temperature starts to drop, it’s guaranteed millions will starve. And if the PCs don’t stop the villain soon, it’ll be billions.

In a fantasy RPG, The Year Without a Summer makes an awesome mystery. Spring fails to come, and there’s no clear reason why. This launches the PCs on a globe-trotting quest for an answer that leads them to a far-off volcano and the portal to Hell that’s been opened within it!

Regardless of your genre, the adventure likely includes at least a brief visit to your fictional Sumbawa-analogue. This can be a memorable adventure site: a large tropical island only just starting to recover, with abandoned towns beginning to erode out of the ash, mudslides destroying recent settlement, refugees building new farms in the highlands (perhaps encountering monsters and mysteries previously undisturbed), and shiploads of slaves arriving in the island’s harbors.

Image credit: Taro Taylor. Released under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Sources:

- 1816, the Year Without a Summer. Melvyn Bragg, Clive Oppenheimer, Jane Stabler, and Lawrence Goldman. BBC Radio 4 (2016)

- “The bright sun was extinguish’d”: The Bologna Prophecy and Byron’s “Darkness” by Jeffrey Vail (1997)

- Excerpts from the letters of Sir Stamford Raffles

- Climatic Aftermath of the 1815 Tambora Eruption in China by Chaochao Gao, Yujuan Gao, Qian Zhang, and Chunming Shi (2017)