Societies have handled the enforcement of laws a lot of different ways in different places and times; the ubiquity of police in the 21st century can make it hard to imagine what other systems might even look like. The way the authorities tracked down suspects in Edo-era Japan (1603-1867) is particularly interesting. The system was a good fit for its time and place, yet it had obvious loopholes known about and exploited at the time. Using a system based on this one in your fictional campaign setting can lead to memorable adventures!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

The Edo period (1603-1867) was the time when Japan was ruled as a unified, fairly centralized state by the Tokugawa family of warrior-aristocrats. The shogun, a sort of military dictator, governed Japan ostensibly in the name of the emperor. In practice, the imperial court was entirely ceremonial, and the Tokugawa shogun actually ran things. It was a period of peace and stability. With little fighting to do, the hereditary warrior class (the samurai) became civil servants that everyone pretended were still ferocious archers and swordsmen. The shogunate kept a close watch on Japan’s local lords, levied them frequently for manpower and supplies, and kept them too weak to rebel.

The country’s shrines and temples were also pressed into service for the nation. Buddhist temples were obliged to maintain census rolls of all the families in nearby villages. Births, deaths, and moves had to be registered with the temple. Every year, the temple worked with local officials to produce an official roster of who lived where and to whom they were related. Temples testified to the roll’s accuracy with a special seal. While it was often illegal for farmers to move between prefectures, those rules were often flouted – but your family still had to keep your original temple up to date on where you were living. Copies of all these census rolls were kept in the capital at Edo (modern Tokyo).

So when authorities wanted to find someone suspected of a crime, they turned to the suspect’s family. They looked the suspect up in the rolls, then issued a warrant to the headman of the village he was registered in or – in the case of residents of cities – the block captain of his registered neighborhood. The authorities would also issue a warrant to the suspect’s registered family. The family had thirty days to find, capture, and bring in their wayward relative. If they couldn’t do it in thirty days, they had to report the state of the search to the relevant officials, who would re-issue the warrant for another thirty days. After six such failures, the family was fined or reprimanded.

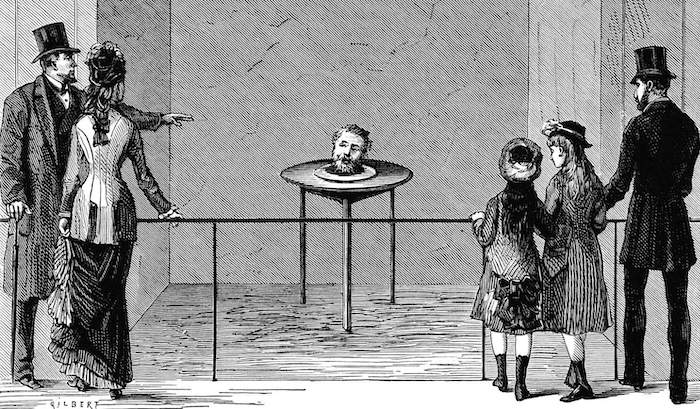

Sometimes particularly heinous crimes would trigger a nationwide manhunt, especially if the family reported the suspect had fled the district, passing beyond the possible reach of a single family of farmers. In this case, shogunal authorities might circulate a description of the suspect across Japan. Theoretically, if the suspect were apprehended by some responsible citizen, the government would then circulate a memorandum announcing the previous warrant and description were closed – though in practice, this requirement might have been less than perfectly observed.

OK, but what about people who didn’t appear in the census rolls? This was not only pretty common, it was even state-sanctioned, which is remarkable considering how important the rolls were for catching criminals. Families could petition the temple to remove relatives from the rolls. They weren’t lying and claiming a family member had died. They were saying their relative might be about to commit a crime, and they didn’t want to be liable. Also, if you fled the village or city block you were registered in, part of the administrative followup was removing you from the rolls. And the punishment for some crimes was exile, which also entailed (you guessed it!) removing you from the census rolls.

Thus, Edo-period Japan had a decent population of people who did not officially exist, including folks who had been officially de-existed by the government itself. These so-called ‘unregistered persons’ were thus free of the primary method the state used to track down suspects. They had no official family, so no relatives could be forced to track them down and turn them in. Some unregistered persons were unregistered because they were career criminals. Some were just unregistered because they’d fallen between the cracks of society. Of course, being unregistered often went hand-in-hand with poverty. Maybe you fled your home village because you had neither land nor work. Maybe you’d been erased as part of a sentence of exile passed for a crime of desperation. The unregistered, then, often became career criminals as a result of their poverty, even if they didn’t start out that way – and it was those same career criminals that the state was (presumably) most often interested in catching. The system was thus deeply impractical, but it was at least philosophically consistent.

So if the people likeliest to be sought as suspects were also the people that the family-detective system was least likely to work on, how did local officials find the suspects they were looking for? The answer is surprisingly modern: confidential informants. People brought in for other crimes would often agree to rat on other people in exchange for a lighter sentence. An informant whose tips were good could get on the payroll of the local magistrate. Of course, for his tips to stay good, these undercover agents had to continue hanging out with criminals, which meant that many – perhaps most – were still committing crimes even as they were ratting out their comrades.

I should mention that there’s a whole world here I’m not touching. There were state-sponsored guilds of unregistered persons. There’s was an entire genre of detective novels and plays produced in the Edo period. This world is very much A Cultural Thing, but I really just wanted to write about the government using families and temples as its first-line tool to arrest suspects.

Beyond intentionally de-registering your potentially troublesome relatives, there were other avenues families could take to avoid having to play detective. For one, they could just refuse. The punishment for failing six consecutive warrants was a reprimand or a fine. If you expected to receive a simple reprimand and felt your family reputation could endure it, you might just not track down your wayward relative. Heck, you might even know where they were and just decline to turn them in. If you expected to receive a fine instead, that only mattered if your family finances couldn’t take the hit. If you were well-off, who cares? An infraction being punishable by fine means it’s legal for the rich.

Setup: A gambler was killed over dice in an alley last night. Their last words – shouted so all the world could hear – were “Tiffany Farra, you stabbed me!” Tiffany Farra is, of course, a notorious troublemaker. People who know her all agree she probably would stab someone to death over a dice game. There are sufficient witnesses to convict Tiffany for murder – but the presumed killer is nowhere to be found! Naturally, she’s an unregistered person, so her family can’t be pressed into service. If the PCs would find her instead, the mayor would be very grateful. Why don’t they start by traveling to Tiffany’s home village in Lucky Valley to see if the temple there has an older copy of the census rolls that still lists Tiffany’s family? The family can’t be pressed into service, but it’s still a good place to start.

Situation: Tiffany Farra is hiding out at the Farra estate in Lucky Valley. Tiffany’s two parents came from very different worlds. One, Tybalt Farra, was from the richest family in the valley. The other, Guarnier Stamfell, was from a dirt-poor homesteading family. Tybalt and Guarnier moved to the big city, but kept Tiffany in touch with both sides of her family. Both parents are dead.

The wealthy Farra family is fond of Tiffany. They’re rich enough that they can pretend not to notice that jewelry goes missing when Tiffany visits. They share Tiffany’s love of tennis and orchids. Tiffany arrived in Lucky Valley a few days before the PCs get there, and the Farras immediately agreed to hide her. They rebuilt the shed by the tennis court – where they used to keep spare nets – so that Tiffany could stay there out of sight. They even put in flower boxes below the windows and filled them with orchids. The Farras are hiding another secret too: they worship one of your setting’s gods of evil. The god has now and then asked nasty favors of them, and in return has blessed them with wealth.

The Stamfell family of Tiffany’s poorer parent can’t stand the woman. Last time she had to lay low, she asked if she could stay with them, since their homestead is remote and doesn’t get many visitors. They hid her. But when Tiffany left, she reported the family’s unregistered (and untaxed) moonshine still to the authorities for a reward. She betrayed the Stamfells, and they’ll never help her again.

Image credit: renfield kuroda, released under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

When the PCs get to Lucky Valley, they’ll find the temple has an older copy of the census rolls that lists Tiffany as belonging to the Farra family (address: “The Farra estate”) and to the Stamfell family (address: “Way back up Reedy Creek”).

If the party travels to the Farra estate, the Farras will invite them in and show them great hospitality in the public-facing side of their mansion. The bulk of the estate is private, though, and is concealed behind hedges and locked doors. That’s where the tennis courts and Tiffany are. The Farras’ hospitality lasts until a PC mentions that they’re looking for Tiffany. Then it’s all cold shoulders and urging the PCs out the door. Relevant Farras include Tiffany’s grandfather Antonio (hard of hearing), his daughter Portia (snooty and quick to laugh), and Portia’s wife the orchid scientist Luisa (always thinking about orchids and not the matter at hand).

Even if the PCs don’t approach the Farras, the temple will still notify the estate that the party pulled their information from the census rolls. The Farras will try to shoo the party out of Lucky Valley. First they’ll hire some local toughs to rough up the PCs. Then they’ll get the temple to investigate the party for heresy. Then they’ll call in a favor with their god to summon some demons to attack the PCs.

If the party travels to the Stamwell homestead, they’ll notice that the creek they have to follow to get there (Reedy Creek) seems to be running dry. At the homestead, they’ll meet Tiffany’s aunt, Dig Stamwell (no-nonsense and suspicious of outsiders), and Dig’s two boys, Root and Branch (incorrigible ten-year-old hellions). Once Dig is confident the PCs are alright to talk to, she’ll tell them she can’t stand Tiffany and would be happy to help the party catch her. But given that the party is looking for her to do them a favor, could they do her one first? Some sort of rock monster resembling a granite glyptodont has moved into the spring that feeds Reedy Creek and stoppered it. Could the PCs kill the rock monster and start the spring flowing again?

If the party gets Dig Stamwell talking, she’ll tell them the whole story about her sibling running off to the big city with some rich Farra, and about how Tiffany hid out here once and burned Dig with the tax collector. She’ll also mention that the only things Tiffany loved more than getting in trouble were tennis and orchids. Dig’s a hard woman. She may also point out that if Tiffany mysteriously disappeared instead of being brought to justice, it might save a lot of people a lot of headache.

Image credit: H. Zell, released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

At some point in visiting the Farras or the Stamwells, the PCs are very likely to conclude that the Farras know where Tiffany is. It would be reasonable for the PCs to conclude (correctly) that the Farras are hiding her.

PCs can sneak onto the private part of the Farra estate and notice that the shed next to the tennis court has been very recently expanded. The clean-up from the construction isn’t done yet. Not only is it way bigger than it needs to be, it’s also really nice. Like, there are flowerboxes on the windows containing orchids. PCs might want to break into the shed and grab Tiffany before the Farras’ hired guards get wind of it. Depending on how your players handle the situation and what you think is dramatically appropriate, Tiffany might or might not be in the ex-shed when the PCs pop in. She might be out walking the grounds after dark or emptying her chamber pot.

In the ex-shed, the PCs can find a long letter documenting the Farra family’s evil deeds on behalf of their secret god. It even contains proof: the names of witnesses that could be called and the locations of (quite literally) where the bodies are buried. The letter is addressed to the head priest at the local temple. It closes with a request for a reward in exchange for these revelations. Tiffany was going to betray the Farras like she betrayed the Stamwells! What the PCs do with this letter is a fun cap to the adventure.

This adventure is, of course, a skeleton. The real fun in using an adventure someone else wrote lies in customizing it to your group. For example, in the above version of the adventure, Dig Stamwell operated an unregistered still. But if a PC (or player for that matter) had a fondness for a different kind of mildly-illegal moneymaking operation, use that instead of the still! It really gets your players excited and kicks things up a notch. Other things you can swap out for something better suited for your party include:

– The glyptodont-like rock monster

– Orchids

– Tennis

– What secret the Farras are keeping

– The source of the Farras’ wealth

– How the Farras try to drive off the PCs

– The religion of the local temple

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Facebook, I’m Molten Sulfur Press. On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp.

Source: Lust, Commerce, and Corruption: An Account of What I Have Seen and Heard by a retired gentleman of Edo (1816). I’m mostly pulling from the commentary in the 2014 edition edited by Mark Teeuwen and Kate Wildman Nakai. The actual text of the work is mostly just an old man complaining about kids these days in vague generalities. An Account of my Unfocused Whining might be a better title. But the introductory material and footnotes are really good!