In or around 1030 AD, two women, three babies, and two dogs asphyxiated to death in a farmhouse in a thriving community at the bottom of a canyon in New Mexico. Was this event a tragic accident or was it murder? Modern archaeologists have investigated the site thoroughly and lean towards accident – but it’s still a mighty suspicious case. This true-crime-adjacent story from the vibrant world of the Ancestral Puebloans of the Medieval American Southwest makes a really interesting mystery to drop into your existing fictional campaign and have your players investigate.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Robert Nichols. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Robert, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

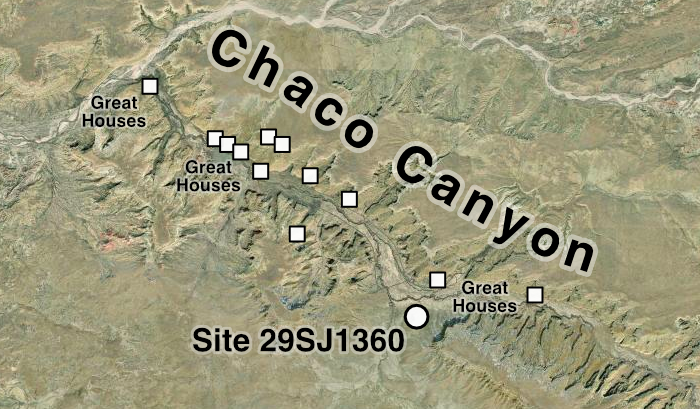

In the year 1030, Chaco Canyon (in what is today New Mexico) was a major center of the Ancestral Puebloan civilization. The canyon had long been home to three ‘great houses’: a sort of massive stone apartment building with important ceremonial spaces and storehouses. But things were changing in exciting ways! The canyon was undergoing a flurry of new construction as the existing great houses were expanded and new ones put up. Outside the canyon, new great houses were being built across the Ancestral Puebloan world, and new farms were springing up in areas that had never before seen cultivation. For while the great houses may have been the focal points of Ancestral Puebloan civilization, the bulk of the people were farmers living on the innumerable small homesteads that filled the landscape.

You might know the Ancestral Puebloans by another name: the Anasazi. That name has largely fallen out of fashion. It’s a Diné (Navajo) word meaning ‘ancestors of our enemies’. Those enemies are the modern Pueblo peoples (Taos, Zuni, Hopi, etc.), who are descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans. Thus, the ‘Anasazi’ name falls into a common pattern in English-language names for Indian nations: white folks showed up somewhere, asked the locals “what’s the name for those guys over there”, and got the response “Oh, those people we’re at war with? We call ‘em the ugly gross stupid bastards.” White folks then dutifully wrote down “ugly gross stupid bastards” and the name stuck. In the interests of better cross-cultural relations, modern archaeologists have decided that the term ‘Anasazi’ is probably not great, and are currently using ‘Ancestral Puebloan’. We’ll see if the name sticks in the long term; some catchier ones have been proposed.

Image credit: Brendakochevar. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Our Chaco Canyon homestead, known by the unwieldy name ‘site 29SJ1360’, was located on a ridge emerging from the north side of Fajada Butte. That put the farmhouse up above the flood plain, but close to the fields in flat lands in the bottom of the canyon. The butte is usually photographed from the north, which gives the erronious sense that it’s in an open plain. It’s not; it’s in a break in the south wall of the canyon, where the Fajada Wash flows into the Chaco Wash. Both streams have water only part of the year, but there’s water down in the soil year-round, which was enough to support the fields.

The homestead was 180 years old by the time of the tragedy in 1030. It consisted of two stone buildings connected by a porch. The smaller building had six rooms; the larger, ten surface rooms and two pit rooms dug six feet into the earth. One pit room was a kiva: a ceremonial space. The other was a winter residence, warmer and easier to heat than the surface rooms. You entered it by ladder through a hole in the timbered roof. A separate dug-out ventilation shaft entered the winter residence through a side wall. A fire made in the hearth thus generated air circulation: smoke escaped out the ladder-hole, which created low pressure in the pit-room, which drew fresh air in through the ventilation shaft. This system will be very relevant later in the post.

The farmers that lived at site 29SJ1360 were typical Ancestral Puebloan peasants. Lines in their teeth tell us they suffered and went without during the great droughts of the 980s and 990s. Half their children died before they left infancy. People who made it to adulthood died around their fortieth birthday. They ate worse, died sooner, and lost more of their children than the rich folks in the great houses that were expanding and multiplying throughout Chaco Canyon. Still, this family made do. They raised dogs to trade for extra food, tools, and pottery. They made their own shale beads, probably for the same purpose. They scraped by, as did so many of their kin, friends, and neighbors. Then tragedy struck.

One night, in the winter of 1030 or thereabouts, two women, three children, a puppy and a dog were sleeping in the pit room when the ventilation shaft stopped working. One, a woman in her late 30s wearing a necklace of four thousand shale beads, seems to have suffocated without waking. She died in her sleep. So did the puppy at her feet and the baby on a yucca mat beside her. Another woman, this one in her early 40s, woke up, but too late. She grabbed a two-year-old child and held it up to the ventilation shaft. But she couldn’t get enough air and collapsed, pinning the child beneath her, and they both suffocated. So did an adult dog nearby and a baby tucked away in a corner.

How could this have happened? Sometimes, if conditions are just so, a thermal inversion can form that traps hot, carbon-monoxide-rich air inside and keeps fresh air from flowing in. It’s awful, but it still happens today, usually in poorly-vented trailers. It’s also possible a branch might have fallen on the ventilation hole and fresh snow have covered it, plugging the shaft.

It’s also possible this was murder. The woman who died in her sleep died with the tips of two stone arrowheads still lodged in her body. She also had a hole in her right ulna (a forearm bone) – maybe a defensive wound? But the arm wound was weeks old; the bone had already begun to heal. Clearly someone had already hurt her, maybe tried to kill her. And there was no shortage of sandstone slabs at the site that could have been dragged over the ventilation hole. Still, if this was murder, why didn’t the dogs bark and wake the sleepers? Dragging a sandstone slab is noisy; it’s not like the dogs wouldn’t have noticed. Consequently, archaeologists chalk this up to an accident.

After the accident, the farmhouse was burned, then abandoned. The burning roof timbers collapsed inwards, preserving the site for future excavation. It’s easy to attribute this to grief. One can picture the rest of the family returning home from a hunting trip or from labor or ritual at a great house, discovering the disaster inside, and setting fire to the house to ensure no one could ever again live in a place where so terrible a thing had happened.

I will point out, though, that there’s an alternate explanation for the deaths that is also consistent with the facts: domestic violence. The wounds on the sleeping woman are unusual for spousal abuse (or something in the same universe), but jealousy, anger, and resentment take many bizarre forms. And if this were a murder and the killer were a family member, the dogs might have woken when they heard the ventilation shaft being blocked, but recognizing the killer, they might have gone right back to sleep without barking. It’s “the dog that didn’t bark” from the Sherlock Holmes short story Silver Blaze. The fire, then, would be not an expression of grief but an act of spite – or an attempt to conceal the murder.

Image credit: Thomson M, released under a CC BY 3.0 license.

At your table, you can have your PCs come across a burned homestead inspired by site 29SJ1360, complete with a pit house winter residence. The question the party has to answer is whether this was tragedy or murder – or, depending on your setting, perhaps a curse or a monster. You have to give the PCs reasons to care. Some parties stumbling upon a smoking ruin might not even check for survivors. Those of a more heroic bent are still unlikely to investigate further if there’s no immediate evidence of foul play. Instead, consider having the overworked and understaffed authorities ask the PCs to investigate the farmstead. Old Man McGucket showed up in town claiming he found his wife, sister-in-law, and three grandkids dead. He gave up, burnt the farmstead, and slumped into town a defeated man. That raised some red flags for the authorities, and they’d like the PCs to dig into it.

If you take this route, you want to add some smoking-gun evidence. Remember the three-clue rule. If you want the PCs to arrive at a particular conclusion, you’ve got to have three ways they can reach it. The players will miss the first one and misinterpret the second, but they’ll get the third. So that said, here are the ways the clues the PCs find should differ from the real, historical clues at site 29SJ1360:

For a tragedy:

– The charred remains of a branch over the ventilation shaft. A dead tree stands beside the shaft, and the positioning of the branch is consistent with it having fallen naturally.

– Burrowing rodents like marmots or prairie dogs have cleared the fresh snow out of the entrances of their burrows.

– There’s lots of unburned wood in the hearth at the center of the pit house. The fire was snuffed out due to lack of oxygen long before it ran out of fuel – though after carbon monoxide had killed everyone in the pit house.

– Most of the fresh snow was melted by the heat of the fire, obscuring Old Man McGucket’s footprints, but there’s nothing suspicious in what remains.

– None of the bodies show any signs of violence besides asphyxiation.

For a murder:

– None of the victims died in their sleep. They all collapsed while standing.

– Scratches on the top of the ventilation shaft suggest a slab of rock was dragged over it, then dragged off it. There are similar scratches on the underside of a nearby piece of rock.

– While there is snow, it’s a few days old and it’s patchy. On the one hand, that means it doesn’t yield useful footprints. On the other, it means it’s the snow fell a few days before everyone asphyxiated, which doesn’t line up with it plugging the shaft.

– A broken arrow is jammed into one of the collapsed roof timbers. Maybe someone was shooting at the ladder-hole in the roof to keep people from escaping.

– One of the slain women has a fresh arrow wound in her shoulder.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on Facebook, Twitter, or Mastodon to increase visibility for the Molten Sulfur Blog!

Source: Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place by David E. Stuart (2014)