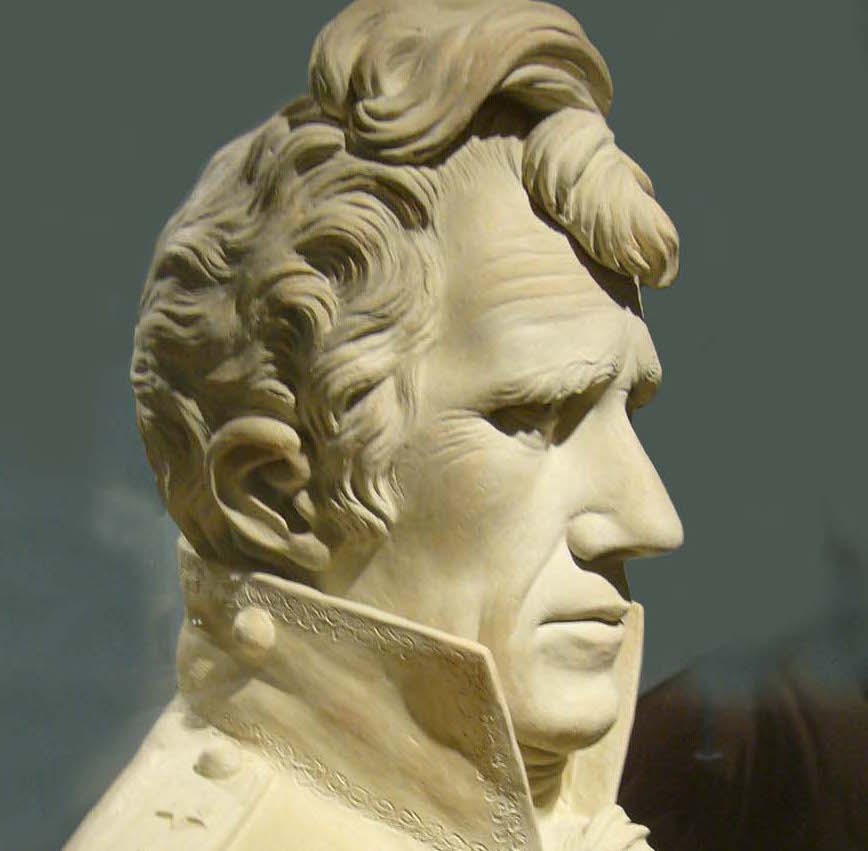

The ‘gentlemen’ of antebellum America practiced many perverse social customs. One of the more appalling ones was dueling. Let’s have a look at how to use dueling as a plot hook at the table by examining a particularly nasty spate of bloodshed featuring America’s most infamous duelist: future president Andrew Jackson!

In 1805, Nashville, Tennessee was a frontier settlement of about 500 people. Jackson was one of the town’s gentlemen of standing. Such men were expected to respond to insults or betrayals by their peers dueling. To fail to issue a challenge (or refuse to accept it) was a sign of cowardice, and could ruin a gentleman’s reputation. Over the next year, two factions of Nashville landowners would clash on the dueling field, set at odds not by ideology or money, but by personal dislike, loyalty to friends, and fueled by gossip and social expectation.

It started with a horserace. Andrew Jackson and an acquaintance named Joseph Erwin both had fine racehorses, and agreed to a race. But before the race, Erwin’s racehorse was lamed, and Erwin had to pay an $800 forfeit. The two men disagreed over how to pay the money. The dispute wasn’t a big deal to either one, but rumors soon swirled that both were complaining they’d been cheated. Then Erwin’s son-in-law, a lawyer named Charles Dickinson, was overheard joking publicly that Jackson’s beloved wife slept around. This was an unforgivable insult. The gentlemen of Nashville started to pick sides: team Jackson vs team Erwin-and-Dickinson.

Things got worse. Jokes and posturing on both sides were perceived as insults by the other side. The insults led to challenges. One man offended someone on the other side by referring him in a newspaper article as “not only honorable, but religious.” I honestly don’t get the joke, but it was enough to trigger a duel. This period of the squabble was marked by a public beating and at least three different duels.

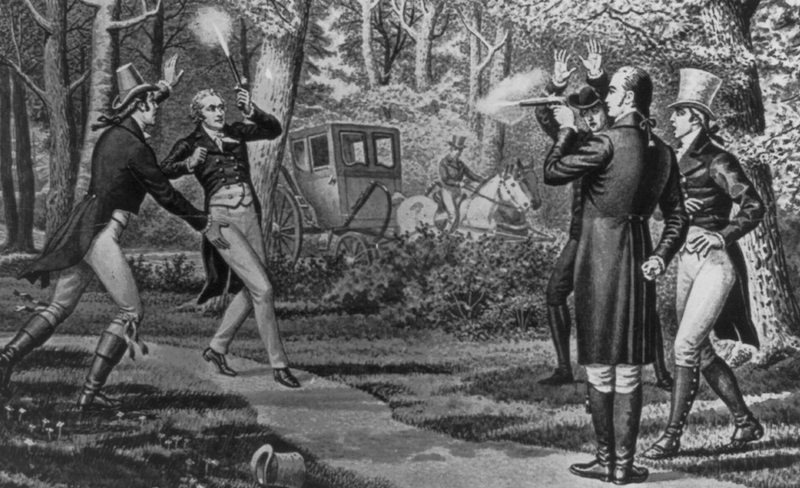

In May of 1806, the dispute came to a head when Jackson challenged Dickinson. Both sides agreed to meet forty miles from Nashville, just across the state line in Kentucky, where dueling was legal. Dickinson’s party left in excellent spirits, for their man was faster and a much better shot than Jackson. Jackson and his second devised a risky gambit to overcome Dickinson’s skill. Jackson would allow himself to get shot. Then, he’d take his time aiming and finish Dickinson off. They were gambling their victory on the hope that Dickinson’s shot wouldn’t be instantly fatal. Even then, it was possible both men might die.

The duel started like Jackson hoped. Dickinson fired, but Jackson was still standing. Dickinson cried out, “Great God! Have I missed him?” Jackson aimed carefully and fired. Dickinson collapsed, bleeding badly from a shot just under his ribs. Jackson’s party quit the field, and only then did Jackson reveal to his friends that Dickinson had shot him in the chest. Miraculously, the ball was deflected by a coat button, and the wound – while serious – was not fatal. Meanwhile, Dickinson lay dying, distraught and not understanding how he could have missed. Jackson forbade anyone from telling the man how close he’d come to victory. It was important to the future president that his enemy not only die, but die miserable.

So let’s talk about the rules of a duel in this time and place – and how you can take advantage of them at the table! While duels were supposed to be as impartial as a coin flip (but with way more blood), people could and did negotiate the rules to rig the event.

The general idea was that the challenger and the challenged would both be given identical single-shot pistols. They’d be some predefined distance apart, and would shoot at each other at the signal. If both parties missed, the duel might be over or might repeat until someone got shot. Each duelist had a representative called a ‘second’, who was permitted to shoot the other duelist if he fled the field before both parties fired.

The seconds also negotiated the rules of the duel in advance. Three important details to hash out were the duelists’ starting distance, starting facing, and whether they were permitted to advance.

– The challenged party set the distance between the combatants. In one duel in which Jackson acted as second, he knew his man was a poor shot, so he insisted the duel be carried out at a distance of only seven feet. At that range, luck and speed would matter more than skill.

– There was no consensus on whether the duelists started the duel facing each other or away from each other. If they started facing each other, they could take careful aim while the officiant counted down “3, 2, 1, fire”. If they started facing away, they had to spin on the word ‘fire’, which could throw off their aim. Duels where the combatants faced each other were probably more often deadly as a result.

– Seconds also negotiated whether the duelists had to fire from their starting points. In one of the duels in the 1805 Nashville squabble, the duelists were permitted to “advance or not, and fire when they pleased”. One duelist fired quickly and missed. The other then walked right up to him and fired into his opponent’s chest from only a foot away. The wounded man lived, but it was a near thing.

At your table, if your big-mouthed PC gets the party in trouble in high society, she could get challenged to a duel. Similarly, if the PCs make the wrong set of friends, they could get pulled into duels (or at the very least acting as seconds), just like Andrew Jackson’s friends.

A duel might be a pretty serious affair for a PC. In many RPG rules systems, the things that let a PC go up against opponents and reliably win are muted in the static, artificial environment of a duel. That advanced body armor doesn’t matter if you’re dueling in normal clothes. That feat that lets you attack three times a round doesn’t matter if you’re dueling with single-shot weapons. It’s really just a roll of the dice.

So the real fun is in rigging the rules! The party will need to figure out what advantages the challenged PC has over her NPC rival, and negotiate the rules so her advantages are maximized and her disadvantages are minimized. Getting the other side to agree to these rules could require a fun combination of lies and concessions.

You might be tempted to up the ‘wow’ factor a little by letting the players negotiate for cool weapons, multi-sided combats, more than one duelist on a side, or bringing in a little color. If you do that, all you’re doing is re-inventing gladiatorial combat. That’s fine, but it defeats the point of a duel. What makes a duel special is how artificial it is. It’s the blandest possible thing, except it ends with a very real chance of someone dying. It strips away all distractions from the main event – swift, sudden violence.