The role of the herald in Medieval western Europe was multifaceted: messenger, diplomat, announcer, and an expert in the system of personal and family insignia called “heraldry”. Starting in 1530 in England and Wales, royal heralds were sent out to verify that everyone using a coat of arms was approved to be doing so and to check the genealogies of everyone involved. It’s a weird, ceremonial role with surprisingly big implications, and it makes great inspiration for an RPG adventure!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

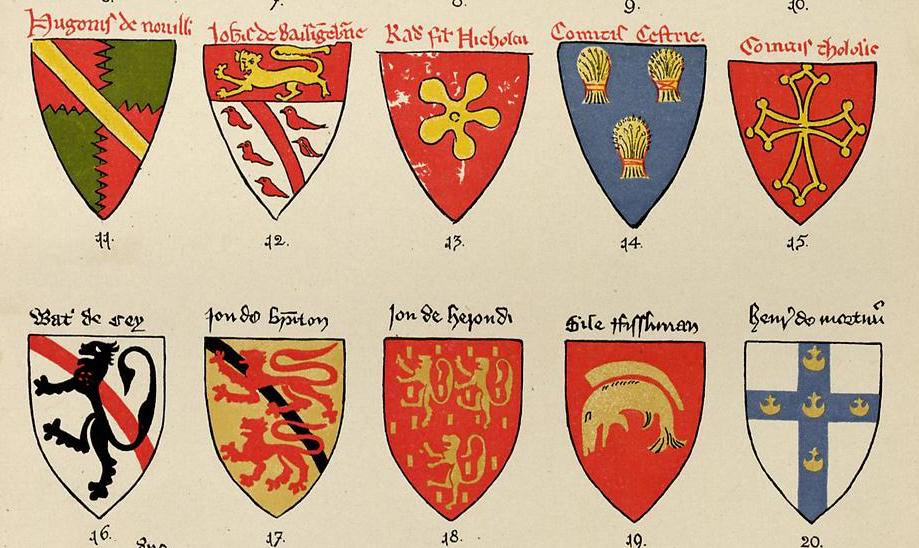

In the early 1100s, nobles began using consistent hereditary devices on seals and banners in England, northern France, the Rhineland, Spain, and Tyrol. By 1200, the tradition of heraldry was firmly established, and its grammar—what colors and sorts of symbols were used, how they might be arranged, and the terminology—was nailed down by 1250. The tradition grew out of tournament culture. Nobles (warrior-aristocrats) and knights (armored heavy cavalry with pretensions of respectability) liked to go to tournaments to show off and be recognized. The heraldic devices that helped them do that then spread to the battlefield. The heralds who announced and ran messages for their highborn employers became the experts in everyone’s insignias. By the 1300s, heralds saw themselves as an international brotherhood, Le Noble Office d’Armes. At the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, both side’s heralds stood together to help one another keep track of which fancy lads were killed. Heralds maintained rolls, some illustrated and some purely descriptive, of which families used which devices and how the individual members of the family put twists on their family arms to create their own personal arms.

Almost as soon as heraldry had rules, some people wanted to break them. One roll of arms from around 1253 lists three different petty nobles using the same arms: Argent a chief gules (white with a red bar on top). At the 1300 siege of Caerlaverock in Scotland, two English knights showed up bearing the same heraldic arms and squabbled over whether one of them should change. As early as the 1400s—and possibly earlier—the kings of England extended their control over the heraldry of their subordinates. This was partly to reduce confusion and partly to have another carrot and stick to influence their vassals. Fail to pay your taxes and maybe the king will take away your family’s right to their ancestral coat of arms. If some knight of no prominence does good work for the king, maybe the king grants his family their first ever patent of arms. In England and Wales, the College of Heralds was formally part of the royal household, reporting to the Earl Marshal, a hereditary court position responsible for matters of ceremony.

In 1530, King Henry VIII of England launched a system of audits to make sure that everyone in England and Wales who was using a coat of arms had a right to it. Henry suspected plenty of petty knights were claiming false pedigrees or just inventing coats of arms wholesale for the prestige that came with them. This was also a period where Europe’s social and military character was changing. Male aristocrats were no longer automatically warriors, and knights didn’t quite dominate the battlefield as they once did. In the midst of this changing landscape, Henry wanted to make sure that some traditions were still being followed.

So Henry sent his heralds into the countryside to check up on things, a system called the Visitations. The system, once started, persisted for centuries. Heralds conducting Visitations carried a patent calling on “all manner [of] noble estates as well spiritual as temporal … all mayors, sheriffs, bailiffs, constables, and all other of our officers, ministers, and subjects” to help the herald “visit among [one an]other your arms and cognizances and to reform the same if it be necessary and requisite and to reform all false armory and arms devised without authority.”

A herald named Sir William Dugdale (operating 1680) would arrive at an inn, then summon everyone above a certain social rank within six or seven miles to meet him there, though he still made house calls for the really fancy people

Heralds on Visitations found all sorts of issues.

A herald named Hawley found graves and church windows bearing unauthorized sigils and arranged to have them defaced (or restored, depending on your perspective).

Sir Edward Dering (dead 1644) was caught inventing an ancient Saxon pedigree. To back it up, he had added fictional ancestors to old manuscripts in his collection and installed faux-old bronzes in a local church.

John Lord Lumley (dead 1609) legitimately had an ancient blueblood pedigree, but burnished it by dragging three funeral effigies of unrelated knights from other churches to install in his church, then added eleven new ones. James I of England/James VI of Scotland (he wore dual crowns) quipped once of Lumley’s ancestors, “I did na ken Adam’s name was Lumley.”

Sir Richard Houghton locked up his wife (by whose inheritance he possessed the castle whose arms he bore) and lived openly with a concubine and their children together. The herald Thomas Tonge reported indignantly that Sir Richard didn’t even bribe him to look the other way.

Going on Visitation could be profitable! As envoys of the king, heralds could expect gifts from the people they met. In 1680, the herald Sir Henry St. George donated his profits from a Visitation of six counties to the College of Heralds to complete the construction of a new hall for the college.

At your table, sending the PCs to investigate the report of an unregistered coat of arms could be a great kickoff to an adventure. They might find the heraldry is definitely several generations old: the graves and windows in the church bear the sigil and are not forgeries. But there’s no evidence that any member of this family, living or dead, was ever actually approved to use this coat of arms. Nonetheless, the family using it is locally powerful. They’ve forged records to complicate the issue. And they have many bondsmen and sworn swords (or bounty hunters or whatever’s right for your fictional setting) to stop the party’s investigations.

Such an adventure works particularly well as a campaign-starter. It gives the PCs the opportunity to organically build relationships with NPCs: scions of the suspect family, bounty hunters, and the questgiver. Then those NPCs can pop up again and again in the campaign.

–

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Check out Shanty Hunters, my award-winning TTRPG about collecting magical sea shanties in the year 1880, then singing them at the table with your friends. The lyrics of the shanties come to life and cause problems for you and for the crew of the ship you sail aboard. It’s up to you to find clues in the song and put things right!

Source: Heralds and Ancestors by Sir Anthony Wagner, K.C.V.O., D. Litt, F.S.A. Garter Principal King of Arms. (1978)