From 1250 to 1266, four successive popes worked to sell the Kingdom of Sicily to any capable European warrior-aristocrat who could afford the steep asking price. The trouble was, the papacy didn’t own Sicily. In fact, Sicily already had a king who was none too pleased with the whole affair. These popes weren’t selling control of Sicily, just recognition of the title. Once you paid, you still had to conquer the kingdom yourself. It’s a weird story, and it makes a really interesting high-level adventure hook. Offer to sell to your epic-tier PCs the one thing they can’t obtain by conquest: legitimacy.

This is part one of a two-part series. This first half focuses on the adventure hook. The second half will run next week and focus on the adventure itself.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Image credit: Alphathon, released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

The Holy Roman Empire during this period looked a little different from how you may be used to thinking about it. At the time, western Europeans were still paying lip service to the idea that it was a revitalization of the old Roman Empire. Its enormous, sprawling borders encompassed just about all of modern Germany, Italy, Austria, Czechia, Slovenia, and Switzerland, and much of modern France and Poland. The emperor was supposed to be the temporal counterpart to the pope. The former handled political and military matters, while the latter handled spiritual ones. In practice, both men usually wanted both kinds of power. The emperor tried to control religious affairs within his borders, while the pope ordered crusades and played the crowned heads of Europe off one another.

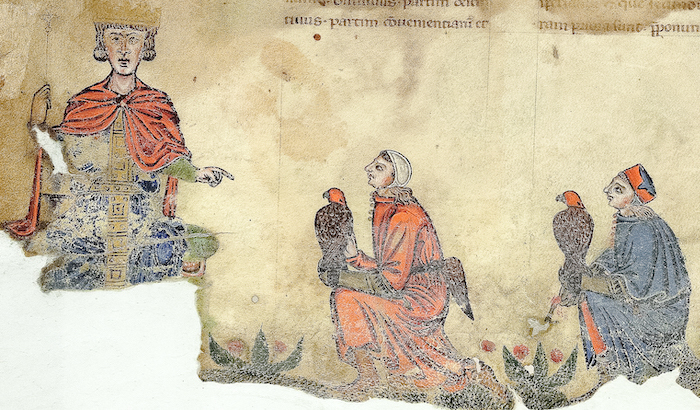

This particular round of trouble started with Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. He was a really interesting dude. He spoke six languages, composed music, commanded armies, and – my favorite – maintained a personal friendship with the sultan of Cairo. His court in Sicily was one of Europe’s great centers of culture. Frederick was also a skilled political power-player. Several of his maneuvers in Italy brought him into direct conflict with Pope Gregory IX, including conquering Italian lands that belonged to the pope. He even besieging Rome itself, the seat of the papacy. When Pope Gregory died, his successor, Pope Innocent IV, continued the feud with Frederick, even ordering a crusade against him and trying (unsuccessfully) to have him poisoned. Frederick died of natural causes in 1250, and the pope could finally take a breath.

Innocent IV was no dummy. He understood that – while Emperor Frederick had been a remarkable man – the papacy’s troubles with the Empire wouldn’t end with Frederick’s death. As long as the Holy Roman Emperor controlled both northern Italy and southern Italy (the latter called the Kingdom of Sicily), Rome and the popes would always have a dagger at their throats. Indeed, Innocent himself was ruling not from Rome, but in exile in Lyon, France. For the papacy to be secure, the Kingdom of Sicily (southern Italy and the island of Sicily) must be taken from the hands of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Image credit: Jörg Blobelt, released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

So Innocent IV put out the call. If anyone would pay off the enormous debts the papacy had accrued fighting wars with Frederick, the pope would declare that person King of Sicily. Of course, Innocent didn’t have the ability to make the Sicilians follow his command. This nominal new king would then have to conquer his theoretical kingdom. Still, the offer wasn’t nothing. Political philosophies of the era were muddy, but most powerful people agreed that God had at least something to do with who was king of what. Having God’s own representative on earth declare that you were the king of such-and-such would help make sure that people would actually treat you like a king. Otherwise, you might not even be able to raise an army to go conquer your desired kingdom. Even if you won the war, your peers might not recognize your claim. Your subjects would rebel whenever possible, your neighbors would conspire to restore the old king you kicked out, and you wouldn’t be invited to sit at the cool kings’ table in the cafeteria.

The first person Pope Innocent IV approached was Richard of Cornwall, the younger brother of the incompetent King Henry III of England. Richard could definitely afford the high price Innocent was charging. Every time King Henry screwed something up, he had to ask Richard to come fix it, and Richard would only do so if bribed. Plus, Richard would rebel every so often, then accept bribes to stop rebelling. Thanks to the bribes, some corruption, and capable stewardship of his own lands, Richard was much richer than the actual King of England. But despite his various rebellions, Richard wasn’t much of a fighter. The idea of buying a kingdom he’d then have to conquer didn’t appeal to him. He quipped that Innocent might as well have told him, “I’ll sell you the moon – just climb up there and take it down.” Richard declined the offer.

Next, Pope Innocent offered Sicily to Charles of Anjou, the younger brother of King Louis IX of France. Charles was newly returned from the Seventh Crusade, which Louis was leading and had been a total disaster. While the mess was mostly Louis’ fault (the dude was a truly awful general), it was also a little bit Pope Innocent’s fault, since his wars against Frederick consumed men and resources that really should have been going to the Seventh Crusade. So offering Sicily to Charles of Anjou was a kind of apology to Louis’ family. Plus, Charles really wanted to be King of Sicily! He’d always resented that his incompetent older brother got to be king, while he – ambitious, ruthless, and cheap – got stuck with the County of Provence, and that only by marriage.

Image credit: Cgoodwin, released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

1250 was a great time for Charles of Anjou to attack Sicily, too. The late Emperor Frederick’s legal heir, his firstborn son Conrad, was up in Germany, the poorer, less-useful part of the Holy Roman Empire. The rich part of the Empire (the Kingdom of Sicily) was under the control of Emperor Frederick’s favorite son, an eighteen-year-old possible bastard named Manfred. Conrad and Manfred were gearing up to go to war with one another for control of the Empire, so now would be the right time for Charles to swoop in and take Sicily while Frederick’s sons were distracted and exhausted from fighting one another.

But Pope Innocent’s schemes came to naught. Much as he wanted it, Charles of Anjou couldn’t take Sicily. He’d promised his brother, King Louis, that he’d stay in France while the king continued his fruitless crusade, and send Louis the supplies the king needed to keep fighting. Plus, France didn’t have the money to pay the pope – Louis had spent it all on the crusade. Charles had to regretfully decline.

The issue evolved. In 1254, Conrad of Germany (Emperor Frederick’s oldest son) died of malaria. His half-brother Manfred wasn’t able to extend rule from Sicily up into Germany, but neither was he distracted by fighting Conrad. Later that same year, Innocent IV died. His successor, Alexander IV, accepted an offer from the incompetent King Henry III of England to buy the throne of Sicily for his second son, Edmund Crouchback. Henry was sad that his eldest son, the future King Edward Longshanks, would get a whole kingdom for himself while Henry’s sweet baby boy Edmund wouldn’t. But King Henry was only able to pay part of the fee. Mistake after mistake cost Henry’s kingdom money it didn’t have. He could only pay his debts by levying taxes on his barons, who dragged their heels. By 1263, the barons were in open revolt, England was plunged into civil war, and Henry had bigger problems than buying a kingdom for Edmund Crouchback. Somewhere in here, the pope (either Alexander IV or his successor Urban IV) withdrew Edmund from consideration. He kept the money King Henry had paid the papacy, though.

By this point, Manfred was well and truly ensconced in Sicily. Funnily enough, the stated original goal of the late Pope Innocent IV had been met. Manfred was King of Sicily, but had no power in Germany. There were two different people claiming to be king of Germany, neither of whom were actually German or in Germany, and no one in Germany paid them any attention anyway. (Those two German kings were the King of Castille, in Spain, and Richard of Cornwall, because Medieval politics were nonsensical.) So there was no Holy Roman Emperor, the lands north and south of Rome were ruled by separate people, and the Holy Roman Empire was no longer a threat to the papacy. Mission accomplished, right?

Eh, not so much. Manfred, though not Emperor, was still warring with the papacy. He was probably more influential in northern Italy than the pope would like. And he let Muslims live in his kingdom and fight in his army. He and Pope Urban IV hated one another. So even though the original reasons for selling Sicily no longer applied – and the idea was on its third pope at this point – Urban kept the offer on the table. Next week we’re going to look at the warrior-aristocrat who finally took him up on it.

Image credit: Ray Oaks, released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

At your table, ‘let me sell you a kingdom I don’t own’ is a great adventure hook for high-level PCs. If you’ve been handing out treasure for the length of one of those long campaigns that Wizards of the Coast seems to believe everyone plays, your PCs probably have more money than they know what to do with. This turns that into an adventure hook. Even if they don’t have that much money, we’ll see next week how to get around that.

At the heart of this adventure hook is the idea of legitimacy. Regardless of how cynical or realpolitik we see ourselves as, we tend to recognize that practical authority and legitimate authority are two different things: whether you are in charge and whether people believe you ought to be in charge. You can absolutely have one without the other.

In RPGs, high-level PCs may be able to carve out their own little fiefdoms, whether that’s a planetary governorship, the iron-fisted control of a crime syndicate, or a castle on the marches. But just because they had the force to take it and hold it doesn’t mean people will respect their authority. Even if the party’s subjects are too cowed to say anything, the party’s peers and neighbors might not treat them right, and it can cause trouble. What Pope Innocent IV offered was legitimacy – and that’s not something you can just conquer your way into.

For this adventure hook to work, your fictional setting has to have someone (like the pope) who has broadly-recognized legitimacy but lacks the practical authority to actually give you what they sold you. Fortunately, RPG settings are rife with such institutions. The Galactic Senate in Star Wars is a great example. If the Senate passes a law saying the PCs are now in control of Tatooine, a large chunk of the setting will nod and agree that the party is the legitimate authority on the planet. Of course, there’s precious few moments in Star Wars where the Galactic Senate has enough power and reach to actually dethrone whatever crime boss is running Tatooine and put the party in charge. No, that’s gonna be up to the PCs. In a high fantasy RPG, the churches of the gods of good can serve a similar function. Most settings have something appropriate: an institution or person who is respected, even admired, but not always obeyed.

And while my focus has been on high-level PCs, for a low-level party, ‘go find me a buyer for this kingdom I don’t control’ is a swell plot hook too, especially for PCs just getting started as political animals. It gives them the opportunity to meet a bunch of powerful NPCs that you can have reappear later in the campaign.

Come back next week for the conclusion of this story – and the adventure to go with the adventure hook!

I’d like to direct your attention to a cool Kickstarter campaign that’s going on right now. Nations & Cannons is a TTRPG about the American Revolution that uses the 5th edition D&D rules set to appeal to (and thereby educate) as large an audience as possible. The design team works hard to highlight the diversity of the participants (not just “dead white guys”), and the books that have come out for Nations & Cannons so far are quite cool. This Kickstarter campaign is to put out a campaign guide, The American Crisis, which covers the war from the Siege of Boston to Valley Forge.

I have agreed to do a small amount of writing for the paperback supplement Poor Richard’s Almanac, so don’t be surprised if you see a Ben Franklin post or two on the blog in the year to come. I get paid the same regardless of whether you back the Kickstarter; I’m recommending it because Nations & Cannons is cool and I believe in it. Check it out!

Source: Four Queens: The Provençal Sisters Who Ruled Europe by Nancy Goldstone (2008)