Shanty Hunters, my upcoming RPG about collecting magical sea shanties in 1880, goes live on Kickstarter in November. This week on the blog, I’d like to offer a sneak peek of the book’s first five pages and one of the historical sea shanties in the shanty songbook. To learn more about Shanty Hunters and be notified when the Kickstarter launches, follow this link!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

“There is a witchery in the sea, its songs and stories, and in the mere sight of a ship.”

– Richard Henry Dana Jr., Two Years Before the Mast (1840)

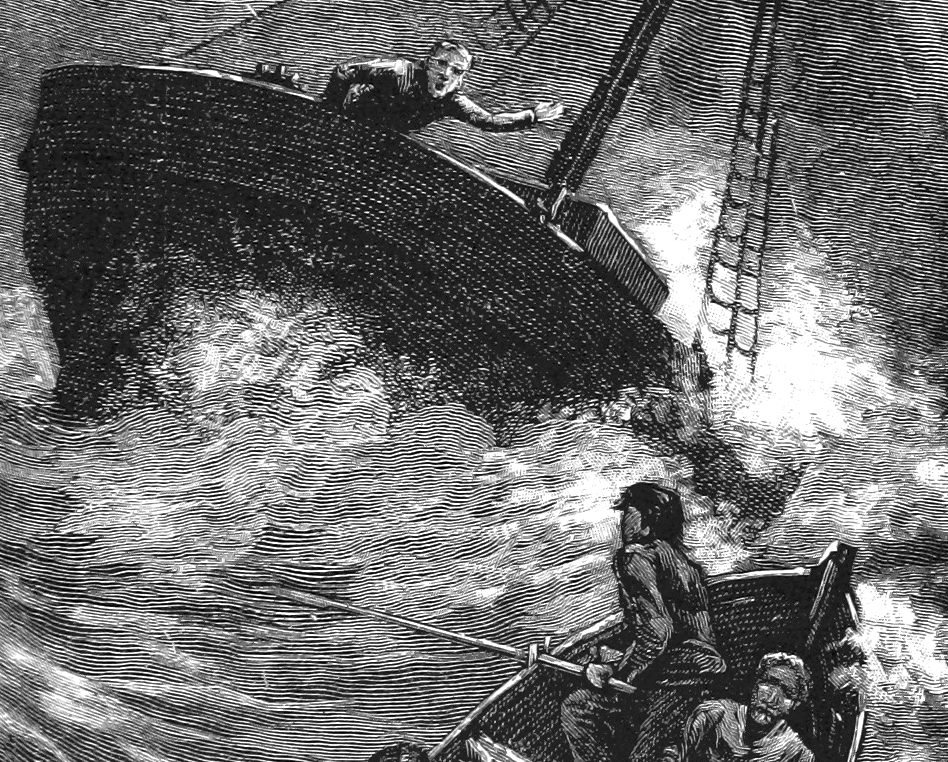

Shanty Hunters is a tabletop RPG where you play as sailors and scholars in the year 1880. The age of sail is dying, and so is the art of the sea shanty, the songs sailors sing as they work. The characters go to sea to document these shanties before they are forgotten. But in Shanty Hunters, shanties are magical. When you write them down, they recapitulate themselves. Events in the song play out in real life. Passengers and crew adopt the roles of characters in the shanty. Imagery from the song manifests itself on deck and in the sea. Only the player characters, the PCs, are unaltered. It’s up to them to survive the strange events they set in motion, to protect the ship from the song’s visions of shipwreck and doom, and to save the innocent non-player characters (NPCs) from fire or drowning or worse. Depending on how the Game Master (GM) flavors these stories, Shanty Hunters adventures can be lighthearted romps, grim horror scenarios, or vexing puzzles.

You usually begin a Shanty Hunters adventure aboard a ship or in a port about to board a ship. You may play through scenes that show the players – who need not know anything about ships or shanties – the information they will need to make informed decisions later in the story. Then the GM passes around copies of this adventure’s shanty. Ideally, you all sing the shanty together! These are rough, workman-like songs; it doesn’t matter if your singing voices are no good. But after the shanty is sung and the characters document it, the song begins to recapitulate itself. Fortunately, you have a vital clue: the lyrics you just sang! You can use the shanty’s lyrics to predict what will happen before it happens, to make sense of the strange events you experience, and to solve the conundrums you encounter.

Shanty Hunters is great for one-shots and short campaigns. Seven sessions is a perfect length. If you play a campaign, the players and the GM should design a villain! This supernatural figure is the reason the shanties recapitulate themselves when written down. He or she opposes the party’s efforts to document the shanty art form. A good villain colors the whole campaign. If you want to run Shanty Hunters as horror, design a creepy or monstrous villain. If you want to run the game as pulp, design a rollicking, swashbuckling villain. Advice and sample villains are presented later in this book.

What Were Shanties?

Shanties were the work songs of sailors. Weary and exhausted men sang these rough tunes to synchronize their efforts. Whether hoisting a sail, tramping a capstan ‘round, or sweating up a jib sheet, every man needed to haul or heave in unison with his shipmates. Timing the strain to the rhythms of a song made the task bearable. The shanty was part of a sailor’s toolkit, as essential as his knife or his marlinspike.

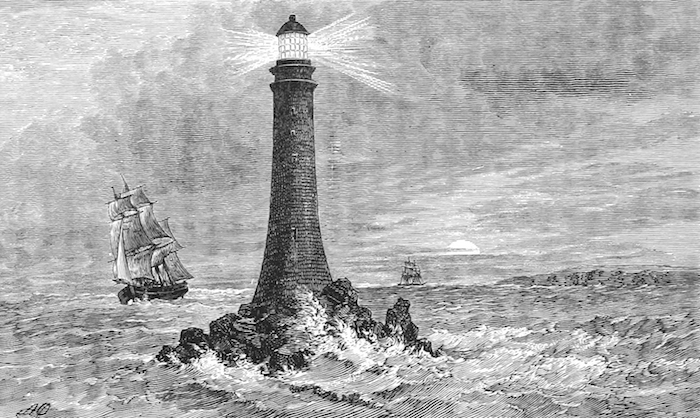

The origins of the sea shanty are lost to us. We find dim mentions of maritime work-songs in documents as far back as the 15th century. This evidence, sadly, is sketchy. While shanties have become associated in our popular consciousness with the Golden Age of Piracy (1650-1730), if buccaneers sang shanties under the hot Caribbean sun, we have no record of it. By the 1800s, efforts were well underway to document this peculiar maritime art form – and just in time! In the latter half of that century, steam began to replace sail on the sea lanes and shanties came under threat. Most shanty-work involved lines and sails, both of which were increasingly scarce aboard steamships. The age of the shanty finally ended in 1929 with the wreck of the Garthpool, the last square-rigger in the British commercial registry.

Shanties were particular to the world’s merchant services. Warships, with their far larger crews and draconian discipline, worked to the tune of a fiddle or a pipe. Merchant ships were still despotic and cruel by our modern standards, but compared to his Jack Tar brother, Merchant John was a wild and free man! It’s here that sailors gave expression to the creativity, storytelling, bawdiness, and vivid imagery that make shanties so beloved still today.

These songs usually had a call-and-response format. The call came from the ship’s ‘shanty-man’, a self-appointed position adopted by a sailor with a capacious mental songbook. The rest of the men on the line hollered back the response. Shanty-men often made the shanties their own by inventing new verses to old standards. Many shanties also included wordless whoops and hollers that gave a shanty-man the opportunity to show off his personal style. Lyrics were enormously variable. The same shanty might have a thousand versions, all equally ‘correct’. The one constant is that shanties were performed a cappella: without musical accompaniment.

Theoretically, shanties were distinct from forebitters. A forebitter was a pleasure song, one a sailor might sing or play with a few of his mates while not on watch. Forebitters were often ballads, love songs, sea songs, and popular songs of the day. Nonetheless, the line between shanties and forebitters was hazy. A forebitter might be used as a pump or capstan shanty (see pp. 131, 118); tramping the capstan ‘round doesn’t require a strong beat or a call-and-response format. And a shanty might be sung as a forebitter if some of the sailors were particularly fond of it. Maritime superstition forbade the singing of shanties outside of work, but many sailors were willing to bend the rules.

English-language shanties as they have come down to us probably owe their greatest musical debts to the folk songs of the British Isles, and to the work songs of enslaved black laborers in the American South and the Caribbean. The 18th and 19th centuries were an era of ‘checker-board crews’ aboard merchant vessels, giving these two powerful musical traditions the chance to mingle. Sailors, no sticklers for propriety, then folded in popular tunes from Latin America to Siam. The love child of these diverse influences was a unique artistic form. I hope it will bring you as much joy and fulfillment as it has brought me.

Who Are the Shanty Hunters?

In Shanty Hunters, the PCs are people who care a lot about learning and preserving sea shanties. They probably care too much. In their pursuit of shanties, they endanger themselves and everyone they sail with. They risk the lives of a shipload of innocents every time they selfishly choose to document a song. The PCs might say they are driven. We might say they’re mad.

PCs are mostly sailors and scholars. In 1880, few people can afford to disappear on long sea voyages for eight months. Sailors can, obviously. Sailor PCs are part of the crew and have responsibilities on the voyage. PCs who aren’t sailors are passengers. They may be independently wealthy, have wealthy patrons, or have some colorful profession that permits them this odd hobby.

Why 1880?

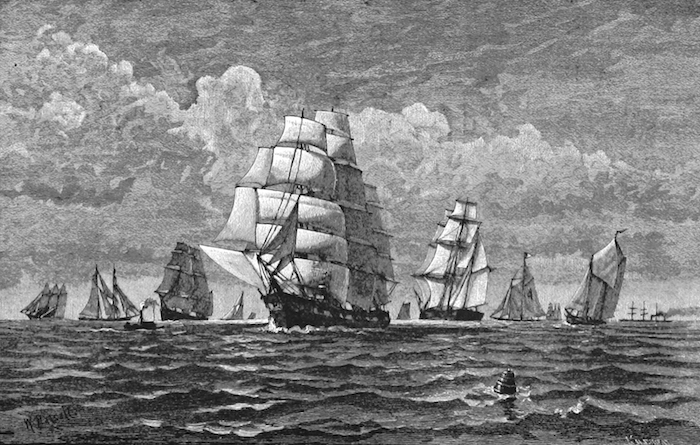

Shanty Hunters is set in 1880 because the writing is on the wall. Merchant sailing ships are still profitable and common, but steamships are more profitable. Every year, steam’s share of the industry grows. The Suez Canal opened in 1869 and has wildly outstripped expectations – but sailing ships can’t use it. Now talks are in progress to build a canal in Panama. And every year steam engines get cheaper and more reliable. The death of commercial sail is coming, and everyone can see it.

That’s not to say sail is dead. No one expects fishermen to trade sails for coal; it’s too expensive. And the docks of every major port are still a forest of masts. But the end is nigh. If you want to document sea shanties while sail is still a large industry, you’d best do it now.

Can This Art Hurt People?

Yes, if you handle it badly. Sailors in 1880 are agents of colonialism, whether they want to be or not. They are also terribly exploited and abused by the same systems they help prop up. Their shanties reflect these facts and the broader worldview of the Victorian Western world. Don’t assume that anyone playing or walking past a game of Shanty Hunters will know this context, and remember that however much your party may enjoy belting out Hanging Johnny (pp. 116-117) at a convention one-shot, there may be someone in the con hall whose father or grandfather was lynched. Know your audience. Be empathetic.

I know that once this game passes from my hands to yours, it ceases to be mine, but I beg of you not to use my baby to hurt other people.

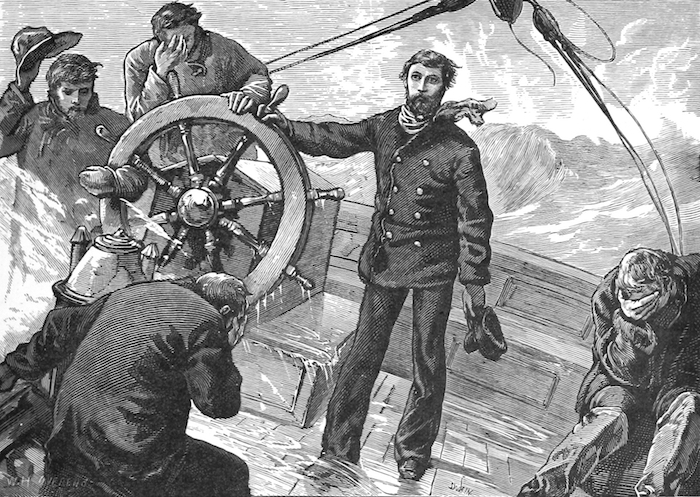

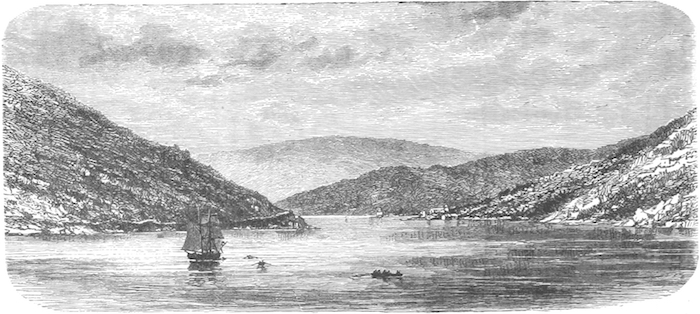

Finally, I’d like to apologize for the the near-total lack of non-white representation in the art in this book. Shanty Hunters is illustrated with public domain art from the era. Period illustrations of non-white sailors exist, but they tend to be horrible caricatures. I chose not to include them. Thus, the illustrations in Shanty Hunters reflect neither the diversity of real sailors in 1880 nor real gamers in the 21st century.

Hanging Johnny

Suggested cover: Hanging Johnny by Stan Hugill, Louis Killen, and the X-Seaman’s Institute on the album Sea Songs Seattle (1979). Stan Hugill was the shanty-man aboard the Garthpool, the last square-rigger in the British merchant registry. He’s also the author of the exceptional book Shanties from the Seven Seas (1961).

They call me Hanging Johnny

Response: Away, boys, away!

They say I hangs for money

Response: So hang, boys, hang!

They say I hangs for money

Response

But hanging is so funny

Response

At first I hanged me daddy

And then I hanged me mammy

Oh yes, I hanged me mother

Me sister and me brother

I hanged me sister Sally

I hanged me whole damn family

And then I hanged me granny

I hanged her up quite canny

I’d hang a ruddy copper

I’d give him the long dropper

I’d hang the bloody bos’n(1)

I’d give him the long dropper

I’d hang the mate and skipper(2)

I’d hang them by their flippers(3)

I’d hang a rotten liar

I’d hang a bloomin’ friar

I’d hang to make things jolly

I’d hang Jill and Jane and Polly

A rope, a beam, a ladder

I’d hang you all together

We’ll hang and haul together

We’ll hang for better weather

1: The bos’n is responsible for the ship’s ropes, anchor, rigging, boats, and deck crew. The term comes from warships. It is still understood in merchant vessels, few of which have a designated bos’n.

2: Captain

3: Hands

To learn more about Shanty Hunters and be notified when the Kickstarter launches, follow this link!