I’ve done two or three posts before about how historical visions of Hell can be turned into encounters that fit well into dungeons and extraplanar adventures. This time, let’s look at facets from four different visions of Hell, not just one!

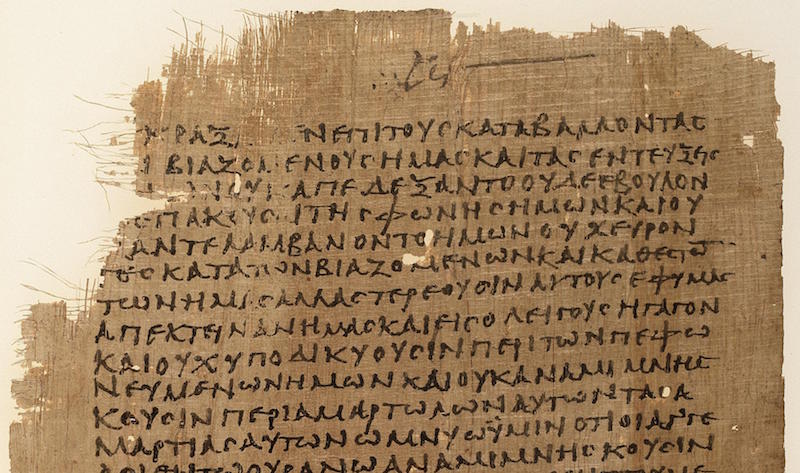

To start with, we’ve got First Enoch, a non-canonical Jewish text. First Enoch 18:12-16 records a Hell for stars that don’t rise at the right time. “Beyond that abyss I saw a place which had no firmament of the heaven above and no firmly founded place beneath it. There was no water on it and no birds; it was a horrible wasteland. There I saw seven stars like great burning mountains, and when I asked about them the angel told me: “This place is the end of Heaven and earth. It has become a prison for the stars and the host of Heaven.” And the stars which roll over the fire have transgressed the Lord’s commandments in the beginning of their rising, for they did not appear at their appointed times. And God was angry with them and bound them for ten thousand years until their guilt was appeased.”

You use this place as a room in a dungeon. Having neither floor nor ceiling (and seven burning stars hanging in the air), crossing it may be a fun challenge.

There was a long-standing Christian idea that part of the joy of being in heaven was being able to witness and contemplate the torments of the damned in Hell. The idea (called ‘the abominable fancy’) is more or less extinct now, but it was really popular for a while. If your PCs visit some sort of hell dimension, they might encounter tourists from a paradise dimension having a good time sightseeing. Roleplay these folks as snooty, holier-than-thou, and maybe just a little emotionally gross, since they seem to enjoy watching their less saintly brethren get tortured. The PCs might even be mistaken for these abominable fanciers. This could be a good deal for a while, since these extraplanar tourists are off-limits to demons. What’s the point of sightseeing in Hell if you can actually be affected by the torments there? Still, if the damned discover that this batch of supposed tourists can be harmed, it might not go well for your party.

–

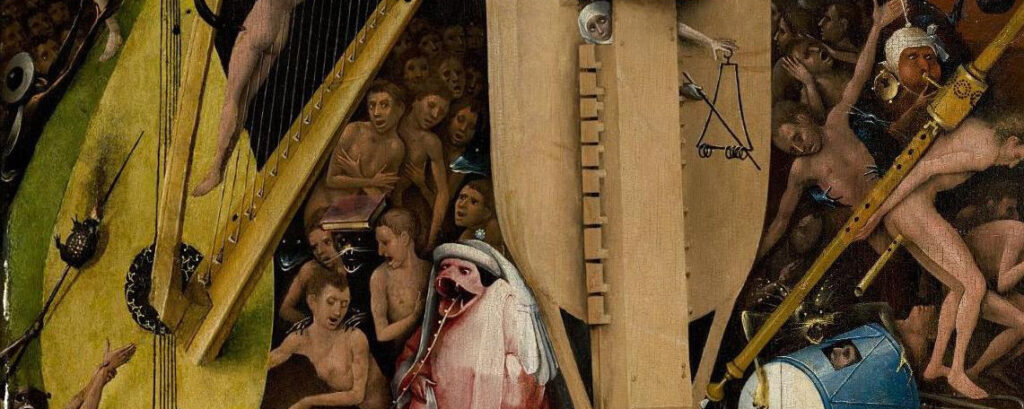

In the Baroque period, the Jesuits (a scholarly/evangelizing order of the Catholic Church) reimagined the torments of Hell in a way that spoke to Europe’s urbanizing character. Their version of Hell was less about skinning knives and branding irons, and more about overcrowding. In this new portrayal, Hell was so tightly packed with sinners that no one inside it could even move. Rich and poor, nobleman and beggar man, all were crammed into a sea of naked unwashed bodies, where every inch of everyone’s skin was pressed up against someone else’s sweating, pustulant flesh, and everyone was wading in everyone else’s excrement. This Hell was claustrophobic and disgusting.

There’s a great portrayal of this style of Hell in James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. In it, a Jesuit preacher delivers a sermon on Hell that sums up this line of thinking pretty well.“In earthly prisons the poor captive has at least some liberty of movement, were it only within the four walls of his cell or in the gloomy yard of his prison. Not so in Hell. There, by reason of the great number of the damned, the prisoners are heaped together in their awful prison… It is a never ending storm of darkness, dark flames and dark smoke of burning brimstone, amid which the bodies are heaped one upon another without even a glimpse of air. … The damned howl and scream at one another, their torture and rage intensified by the presence of beings tortured and raging like themselves. All sense of humanity is forgotten.”

Not unlike the star prison in First Enoch, dropping a Jesuit Hell room in a dungeon could be a fun puzzle. With such a press of bodies in the room, all howling and tearing at one another, how do the PCs get from one side of the room to the other, and continue on with their adventure? The obvious answer (“We cut our way through!”) doesn’t work on the damned. They’re already dead, and their wounds necessarily heal immediately. Otherwise, once they tore each other apart, they’d stay like that and their agony would be over. Eternal torment requires eternal healing.

Finally, we have an odd vision from Plutarch, who ascribes it to a man named Thespesius. Thespesius saw the souls of the recently dead rising from below in fiery bubbles. The bubbles pop, and the souls come forth in forms resembling their earthly appearance, but swifter and nimbler. Some of the souls leap upwards, ascending skyward in a straight line. Others spin round and round, their splayed limbs like the spokes of a wheel. The spinning souls stick around for a while. Some ultimately ascend, but the rest eventually descend into the depths.

NPCs emerging from fiery bubbles to spin around for a bit could be a lot of fun to roleplay with. They probably won’t have any local knowledge of the dungeon or plane in which they find themselves, but their experiences might give the PCs valuable clues to figure out how this adventure site works. As soon as the conversation seems to be reaching an end (or when you want to introduce a dramatic interruption), the NPC announces “Oh! I think it’s happening!” and rockets off either to Heaven or to Hell.