Back in February of 2018, I wrote about Tarang, a remote village of farmers and traders in the Nepalese Himalayas that serves as a ‘hinge’ between its Nepali Hindu neighbors to the south and its Tibetan Buddhist neighbors to the north. Back in 1968, Tarang was undergoing many changes, one of which was the introduction of potatoes. That introduces the possibility for a nefarious mystery! Let’s take a look.

In the early 20th century, a Buddhist monk living in Tarang brought some potatoes to the village from a village to the west. It took a few years, but Tarangites eventually discovered that potatoes grow very well in the steep mountain fields of the remote village. By the time the ‘60s arrived, potatoes had changed the social dynamic in Tarang.

Potatoes have much higher crop yields than Tarang’s traditional grains, barley and chinu millet. No one eats potatoes if they can help it (grain is a higher-status food), but for poor villagers without much farmland to work, it’s still possible to grow enough potatoes to get you through the winter. Before potatoes, poor families’ grain stocks would run out halfway through the season, and they would have to beg for grain from the richer families who owned and worked more cropland. Tarangites being a neighborly bunch, the richer families were happy to share what they had in exchange for labor. In the 1960s, poorer Tarangites no longer had to go begging, and the richer ones lost an important source of winter labor.

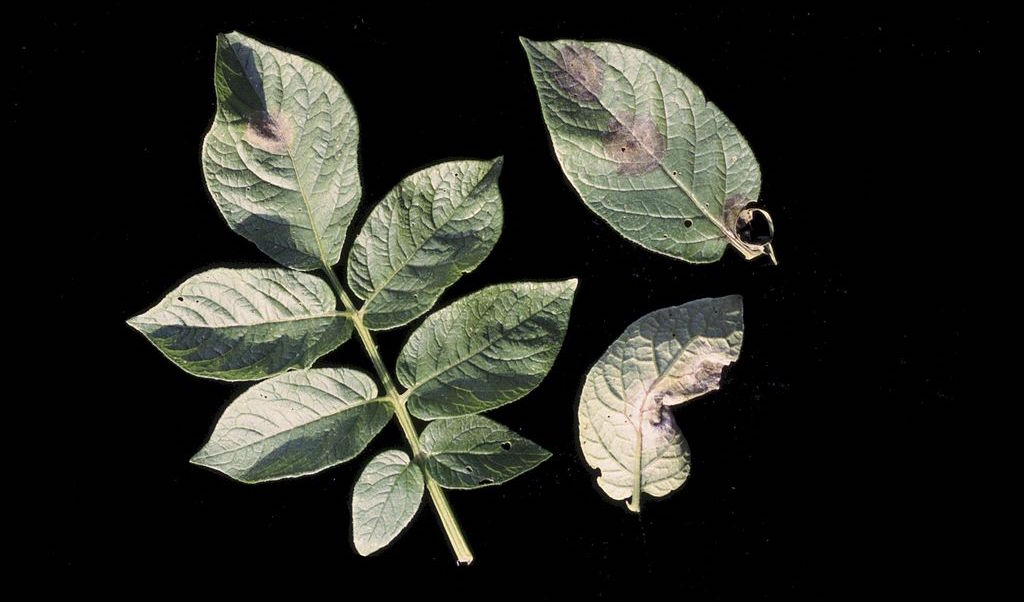

At your table, you could make a mystery based on a situation like this one. Someone rich in your Tarang-analogue (perhaps a thalu, one of the village’s charismatic dispute-settlers) may be upset that he no longer has a ready supply of labor to get his work done. So he secretly imports a potato blight.

The PCs may encounter a trader from Tarang in some other town, who, when he learns who the PCs are, beg them to return with him to his village and investigate this. Tarang is too remote for plagues, he says, and doesn’t suffer droughts. It has to be something nefarious. Tarang’s poor farmers are distraught at losing their potatoes, while the rich farmers (who enjoy a hefty surplus of barley and chinu millet) are looking forward to having so much labor available to them this winter that they can get away with paying their poor neighbors next to nothing.

If the PCs investigate, they’ll find the disease isn’t magical, but it is the same strain of potato blight that caused the 1845-49 Great Famine in Ireland. Which shouldn’t even be possible! That strain’s been effectively extinct for a hundred years! Another helpful clue may be that the thalu has been very vocal about his desire to renovate all the walls of the terraces of his many fields. Renovating even one wall is a back-breaking effort. Renovating all of them will require a lot of extra labor.

The core clue is that the thalu recently visited his son, who’s attending university on a scholarship in Kathmandu. He’s the only person to have made a major trip outside of normal trading patterns in the past year. The thalu’s son is studying plant disease genetics, and has access to samples of the Irish potato blight. He provided his father with a sample of the blight to bring home and spread on a few fields. The thalu still has the empty vial in his house. It’s the only container like it in the village, and is labeled in English, a language no one in Tarang can read.

If the PCs go to someone in authority for help, they may get two very different stories. Many of the local shamans and all of the local Buddhist monks are poor. They’re likely to see this blight as a huge problem and will help any way they can. If the PCs go to someone with political authority, they’ll wind up talking to the thalu, who will assure the PCs that this is no big deal. No one will starve, he tells them. The village has an established system of work-for-food that will get the poor through the winter. They might as well go home.

If the PCs accuse the thalu of this crime, they will find themselves opposed by his followers. ‘Thalu’ is not an appointed or inherited position. It’s a term of respect for a charismatic person with a strong track record of resolving disputes. Thalus accumulate followers who trust their judgement. PCs may be wise to get some of the village’s other thalus on their side, or at least develop a strong base of support among the village poor. Otherwise, the PCs may be forced out of Tarang.

Because Taranpurians are traders, moving goods between Nepal’s Hindu south and Buddhist north, the consequences of the PCs’ investigation may follow them. Some Tarangites even take trains from the Nepali lowlands as far away as Kolkata, India, to buy gold. So regardless of where you want to situate your Tarang-analogue in your campaign world, the PCs may come into contact with Taranpurians again. If the village is grateful for their actions, these Taranpurians may help the PCs. The village is resentful, Taranpgurians may become an unexpected thorn in their sides.

–

(As before, this post draws heavily from Trans-Himalayan Traders: Economy, Society & Culture in Northwest Nepal by James F. Fisher. He’s a super friendly guy, and asked that I include his email address in the post. It’s jfisher at carleton dot edu)

Image credit: Mary Ann Hansen, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, released under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.