The palace intrigue between Suleyman, the King of Mali, and his senior wife Kassi is a brilliant little historical anecdote. Involving the PCs in a life-or-death game of power and legitimacy between two NPCs based on Suleyman and Kassi would be an amazing adventure. As a bonus, the story is bound up in some major historical themes that only make the whole thing better. Let’s take a look!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

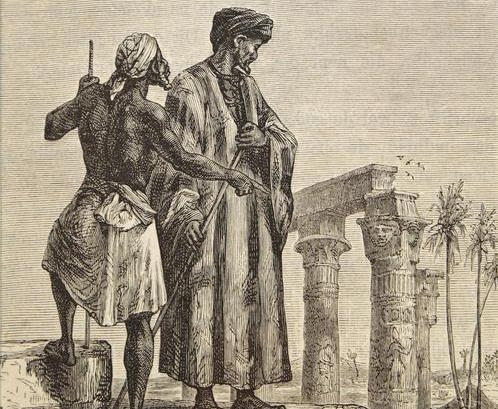

I’ve written before about the 14th-century Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta, whose memoirs recount his journeys across the Muslim world – as far west as Spain, and as far east as China. In 1352-53, his travels took him south, into the kingdom of Mali, where he spent a few months at the court of the mansa, or king. There he witnessed an absolutely fascinating piece of palace intrigue.

The mansa of Mali was a man named Suleyman. He was the uncle of the previous mansa, and brother of the king before that, the famous Mansa Musa. Suleyman’s senior wife, Kassi, was a co-equal ruler, consistent with then-traditional Malian practices. Also consistent with tradition, Suleyman and Kassi were cousins: their fathers were brothers.

While Ibn Battuta was in the capital, Suleyman had Kassi imprisoned in the home of one of his military commanders. The Mansa appointed one of his lesser wives to her place: a commoner named Banju. Ibn Battuta doesn’t tell us why Suleyman did this. Did he have stronger feelings for the (almost certainly younger) Banju? Had he tired of sharing the throne with a co-equal ruler, and wanted a queen he could control? Either way, Kassi wasn’t going to take this lying down.

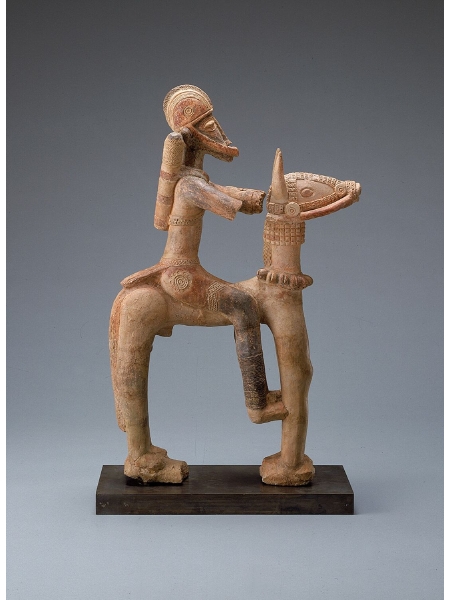

Image credit: Albert Herring, released under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Suleyman had the loyalty of the army, but Kassi had the loyalty of her family – who were also Suleyman’s family and comprised the royal court. Kassi’s sisters visited Banju to congratulate her on her queenship, but declined to perform the ritual obeisance of dusting their heads. When Suleyman released Kassi, her sisters dusted their heads when they visited her, even though she was no longer the Queen (according to Suleyman, anyway). Suleyman grew angry and Kassi’s cousins took sanctuary in a mosque. Suleyman had no choice but to pardon them. What was he going to do, punish his own cousins?

Then Kassi made a long show of her legitimacy. Every day, she traveled to the palace, riding at the head of a long procession of slaves with dusted heads. The court was all atwitter with rumors and gossip. Suleyman was still ‘winning’ this fight with his wife, but he looked like an idiot.

So the mansa investigated Kassi. He seized one of her slaves and, one can infer, tortured her. The slave reported that she had passed messages between Kassi and the queen’s brother, Jatal. Sueyman had tried to arrest Jatal for unspecified crimes, but Jatal fled the country. Kassi invited her brother to return to Mali and seize the throne from Suleyman. The army clamored for Suleyman to execute Kassi. She took sanctuary in the home of her imam, temporarily safe from her husband.

And then the story just… ends. Ibn Battuta picked this moment to leave the capital, so we have no way to know who won the squabble. The succession of the next few musas doesn’t shine much of a light either, as it skips around without revealing which branch of the family became the ‘main’ one. So much that was once known has been lost! Even in a highly literate society society like Mali’s, little has been translated, and of that even less is available. Ibn Battuta offers us this narrow window onto a fascinating story, then slams the window shut before we know the ending.

Image credit: Weetjesman. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

You should always pause before ascribing narrative themes to history. This is doubly true when dealing with a single, solitary event. And triply true when your best source is three pages written by a tourist and mediocre scholar who didn’t even speak the local language! But this bit of palace intrigue is redolent with powerful historical forces that are easy to distill into comprehensible narratives! You can then use those narratives to enrich a fictionalized version of this feud in your campaign.

The first is the tension between, on the one hand, the hard power of armies, soldiers, and prisons, and on the other hand, the soft power of family, tradition, influence, and legitimacy. It’s very clear Mansa Suleyman controls the army, but Kassi has the loyalty of most of their family and the support of tradition. Suleyman can’t do anything permanent against Kassi until he uncovers (or fabricates) evidence of treason. His attempts to operate outside traditional bounds make him look ridiculous and may embolden his rivals, like his cousin Jatal.

If you want to use the Suleyman vs. Kassi palace intrigue as a template for a political drama at your table and you want to play up the hard power vs. soft power theme, give your NPCs influence and aesthetic that play up their power. Your fictional Suleyman-analogue might be a military dictator, a barbarian warchief, or a reaver warrior-queen. Give them lots of guards and soldiers, a uniform covered in medals, and songs about their great victories. Your Kassi-analogue could be a beloved religious figure, a politician democratically elected in a landslide, or a tribal elder. Give them the power to sway people’s opinions, and surround them with cheering crowds!

Image credit: The Smithsonian Institute.

Another theme you can read into this story is one of religion and gender. Many West African societies historically practiced matrilineal inheritance of power. While rulers were still usually men, the next king wouldn’t be the son of the old king, but rather the son of his sister or other female relative. It’s possible (albeit unprovable) that the kingdom of Mali practiced something similar. But the mansas of Mali were good Muslims, and Islam mandates at least partial patrilineal inheritance: privileging sons over daughters. Mali had adopted Islam only in the past 100-300 years. It’s entirely possible that Suleyman and Kassi’s intrigue was a part of a larger culture war between outside cultural influence carried by Islam (including by Suleyman’s grasp for power) and pre-Islamic Malian tradition (including Kassi’s struggle to retain her influence).

In fictionalizing this event, if you want to lean into the outside culture vs. traditional culture theme, have the two NPCs strongly embody their respective cultures. Make your fictional Suleyman-analogue all about the new, outside culture: he dresses like a foreigner, prefers to speak the foreign tongue, surrounds himself with foreign-born courtiers, and privileges foreign gods. By contrast, you can make your Kassi-analogue a hyper-traditionalist. She wears fashions that would have been current centuries ago, speaks with an old-timey grammar, disdains modern technologies (at least those introduced by foreigners), and is punctilious about native religious practice.

Or you could disregard historical themes entirely! Play this one as driven solely by individual human concerns: the pettiness, jealousy, and self-interest of all the players in this little drama. Who has time for grand historical forces when you’re a king in love with a commoner, a spurned wife, or a power-hungry rival to the throne? If you want to lean into this theme, dispense with as much of the aesthetics of power as possible. Don’t fill the stage with guards, servants, and hangers-on. This isn’t Gibbons’ Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire anymore, it’s Shakespeare. The players may be kings, queens, and nobles, but play them as normal people driven by fundamentally human passions – without an ostentatious backdrop that could distract from that.