In 1888, the Swahili coast of what is today Tanzania rose up in revolt against the Sultanate of Zanzibar, triggered by the arrogance of the sultan’s new German ‘friends’. The revolt was particularly memorable at the trading town of Pangani. But while German shortsightedness may have provided the instigating incident, Pangani had been moving towards revolt for a long time. The town was conflict heaped atop conflict, just waiting to explode – and then some dummy set it off. The Pangani revolt is a really interesting story in its own right, and it’s a great illustration of how to build an RPG scenario as a powder keg with matches scattered all around.

This week, we’re going to talk about Pangani, its history before the revolt, how the revolt went down, and all the factions at one another’s throats. Next week we’re going to look at six interesting political power-players active during the revolt.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

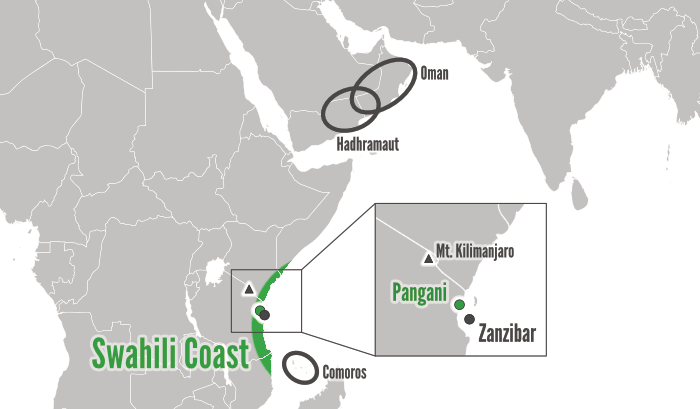

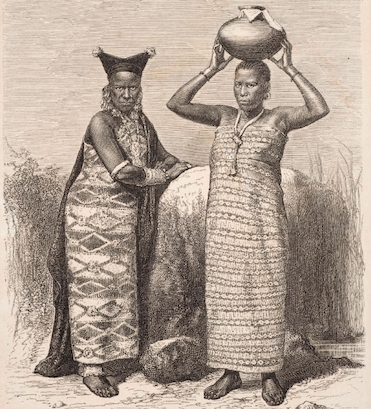

The Swahili coast stretches from southern Somalia to northern Mozambique. For centuries it was an important part of the Indian Ocean trading network, supplying merchants from as far afield as Arabia, India, and Indonesia. The coastal trading towns were governed by Swahili-speaking African Muslims who claimed descent from fictitious Middle Eastern ancestors. These aristocrats are called ‘Shirazis’ after the Persian port of Shiraz, from which many of them claim their ancestors came. Shirazis’ biggest source of wealth was sponsoring or leading expeditions as far inland as Mt. Kilimanjaro to buy elephant ivory and enslaved prisoners of war. Back in town, they sold the ivory to Hindu merchants who sent it along to British India, and they sold the enslaved prisoners to Arab merchants who carried them to the Arabian peninsula. Shirazis were economic middlemen. They prided themselves on their urbanity and sophistication, in the style of aristocrats the world over. Their wealth let them be generous, which was essential to staying near the top of the local social order. Gift-giving let Shirazis show their piety (Islam encourages generosity) and bought the loyalty of their clients.

The bulk of the people living in towns like Pangani were not Shirazis. Some were poorer Swahilis born on the coast. Some were immigrants from abroad looking for opportunities: folks from farther inland in Africa, from the Comoros, from Hadramaut in the Arabian Peninsula, and from more places besides. Many were slaves. Swahili traditions of slavery were complicated; there were many categories of slavery, and some people moved between them. Slavery was usually hereditary, but it was not as harsh as New World chattel slavery. Some enslaved people were wealthy and led their own inland trading expeditions. Others were lowly and hard-done-by. Most of the enslaved worked to advance their social standing by becoming husbands, mothers, Muslims, entrepreneurs, businessmen, members of dance societies, holders of public titles, and other statuses that made them respectable members of society. Immigrants and the coastal-born poor pursued the same advancements. This upward mobility was at least partially funded by Shirazi largesse, even for the enslaved.

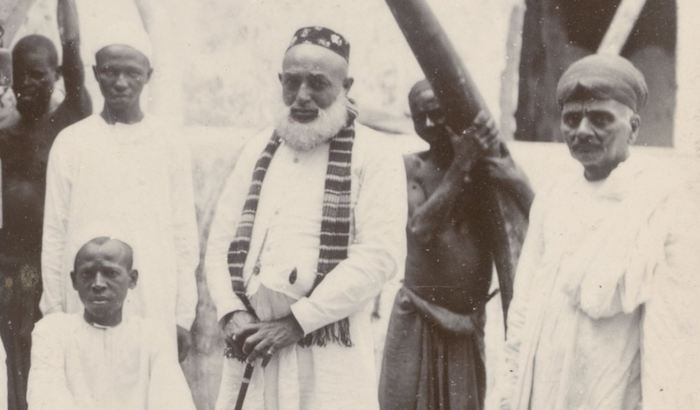

Atop this mass of townsfolk sat the representatives of the Sultanate of Zanzibar. In the 1830s, the rulers of Oman, in the southeast of the Arabian Peninsula, moved their court to the island of Zanzibar, off the Swahili coast. The Busaid royal family had wealth and religious authority. They controlled the Zanzibari ports, which were among the most convenient for trading with India, Arabia, and Europe. The Omanis appointed governors over the Swahili towns, who tended to give more than they took. Shirazis who got in good with the Busaids received gifts, fancy titles, and assistance arranging foreign trade. Business boomed under Busaid management. The Shirazis got richer, and they shared their new wealth. This gift-giving earned them social and political capital, kept them on top (albeit beneath the Busaids), and made life better for the poor and enslaved at the bottom of the heap.

It’s worth noting that while the Busaids lost Zanzibar in 1963, a different branch of the family rules in Oman to this day.

Indian merchants – mostly Hindu, some Muslim – had long been a staple of economic life in Pangani. With the Busaids guaranteeing stability, these merchants were able to offer more and more credit to Shirazis launching expeditions inland to buy ivory and enslaved people. Easy access to credit proved dangerous. Each expedition was a gamble! The Shirazis of Pangani maintained good relations with the chiefs farther inland, but year by year they had to venture farther into the backcountry, where they didn’t have long-standing trade relationships. Local hunters armed with the guns and ammunition the Shirazis gave in payment extirpated elephant populations. Inland wars fueled by cheap gunpowder and selling captured prisoners made the business environment unpredictable. One contemporaneous observer estimated that for every five expeditions an Indian merchant paid for, one would be a great success, two would break even (for the merchant; the expedition’s leader probably earned nothing), and two would suffer major financial losses. The outstanding debt on the failed loans forced unlucky Shirazi traders into expedition after expedition, hoping to get lucky and pay it all off. Those who repeatedly failed to pay their debts were jailed by the Busaid governors. Busaid guarantees that debtors would be imprisoned kept credit flowing, letting Shirazis overextend themselves financially, with predictable results.

The threat of jail for nonpayment of debts drove many Shirazi traders to an even more dangerous line of credit. Busaid successes attracted wealthy settlers from the Arabian peninsula to the Swahili coast. They wanted to establish sugar plantations. The global sugar market was hot, demand was high in the African interior, and the Swahili coast had the right terrain and the ready access to enslaved labor that was needed to make sugar-growing profitable. For this, the settlers needed land on which to build their new estates. They offered Shirazi traders who were down on their luck large loans, asking that the Shirazis offer the lands they owned as collateral. This was not a mortgage; Islam forbids usury. The terms were more akin to what you’d get from a pawn shop. But these loans proved almost impossible to pay off. By the 1860s, Arab settlers were foreclosing on land in units large enough to establish sugar plantations. Unlike in the Swahili model(s) of slavery, sugar plantations needed to exploit and break people in the style of the chattel slavery practiced in the American South, the Caribbean, and Brazil. Things were changing – and not for the better for most people.

In 1873, the enslaved workers on the Pangani sugar plantations organized a mass escape. Men, women, and children from across the plantations all fled on the same night. Judging by the drop in the next year’s sugar production, over half of the enslaved sugar workers might have made it out. They regrouped 25 miles south at a place called Makorora, built a fort, and drove off the mercenary expedition the Busaids sent to re-enslave them. From Makorora, these self-emancipated slaves served as a magnet for runaways, both from the plantations and from the Shirazis. Unable to retake Makorora, the Busaid sultan Barghash bin Said manumitted the fort’s residents.

What you had, then, in 1880s Pangani was a system that no longer worked. The local elites (the Shirazis) had initially benefitted from Busaid rule, but now found themselves poorer than before. Many could no longer afford the patronage and gift-giving that retained the loyalty of their clients and slaves. As for the poor and the enslaved, the spread of Arab-owned sugar plantations meant that more people were moving down the social ladder (into chattel slavery) than up it. And the Busaids who had created this new system were too focused on change coming from a different direction to realize how fragile their position had become.

The British had long been allies of the Busaids. All that ivory and all those debt payments were flowing via Indian merchants to British-controlled India. One of Sultan Barghash’s chief advisors was the British consul, and the head of the Zanzibari army was a British lieutenant. The British didn’t want to replace the Busaids. They wanted a strong, stable Busaid government that encouraged trade that the British could tax back in India. Why do the work of governing the Swahili coast when the Busaids would do it for you for free?

But the Germans had started sniffing around. The German East Africa Company (the DOAG) was founded in 1884 by a group of young German malcontents who had visions of becoming the next Cortez. We’ll skip over their incompetent attempts to conquer the lands inland of the Swahili coast with a handful of German adventurers. The outcome for them was even worse than if they’d been beaten back: they were ignored, then shooed out, largely bloodlessly, like ejecting crying children. But they’d attracted enough interest in Berlin that when the European powers partitioned Africa in the mid 1880s, the British reluctantly permitted the lands inland of the Swahili coast to be declared a German sphere of influence. This made Sultan Barghash livid. He didn’t control those lands, but neither did he want those incompetents in the DOAG stirring up trouble in his backyard! And then he died before he could do anything about it.

In 1888, Barghash was succeeded by a new, pliable sultan named Khalifa. Khalifa quickly signed a treaty with the DOAG that he probably didn’t quite understand, and that he probably didn’t get much input on from his councilors or from the British, let alone from the Shirazis. The biggest concession in the treaty was the easiest to misunderstand: Sultan Khalifa granted the DOAG the authority to govern the Swahili coast in his name. The Busaids had long ‘farmed out’ much of their administration. Collecting customs duties is a pain. It’s much easier to hold an auction where people bid on the right to collect them in your stead. You get a lump sum up front, and they get to keep all the customs duties they collect. In Pangani in particular, Indian merchants had long paid to handle customs collection. Everyone who hadn’t read the fine print of the treaty (so everyone except the DOAG) presumably understood that Sultan Khalifa was just transferring those responsibilities from the Indian merchants to the DOAG. Except in truth, the Germans were getting all the rights and responsibilities of government, from conducting wars to enforcing justice.

In mid-August 1888, a longtime DOAG employee and incompetent weasel named Emil von Zelewski arrived in Pangani. Remember, the town was already in grave danger of some sort of uprising. The Shirazis, the local elites, were all out of money. The plantation owners and the Indian merchants held the Shirazis in their debt, and were counting on the threat of Busaid jail cells to protect their investments. But the Busaids were now led by a weak, untested new sovereign. The poor and the enslaved no longer had any reason to listen to their Shirazi superiors, as they no longer received patronage or generosity. The enslaved workers on the sugar plantations despised their masters and had a fort only 25 miles away they could flee to (though the self-emancipated citizens of Makorora sometimes ransomed runaways back to the planters). This society wasn’t working, and one way or another, it was about to reo-order itself. And because rifles were an important trade good, there were so many guns in Pangani, that reordering would probably be violent. The town was just waiting for a precipitating incident. Zelewski provided it.

In mid-August of 1888, there were two festivals back to back. The first was the local solar New Year, and the second was the religious holiday of Eid al-Adha. That meant Pangani was full of folks from the countryside and the interior here to enjoy the celebrations. There would be music, dancing, competitive feasting (where Shirazis strove to put out the best spread in town), and zikri, where Sufi mystics danced to the beat of a drum while chanting the names of God. Furthermore, it was the end of caravan season, so Pangani was full of porters just returned from the hinterlands with pockets full of money to spend. Zelewski somehow failed to notice any of this. So, unknowingly, he was about to light Pangani’s fuse in front of the largest possible audience.

First, Zelewski informed the resident Busaid governor, Abdulgawi bin Abdallah, that he was out of a job; Zelewski was the new big dog in town, and he had a letter from the sultan to prove it. Then, with a typical European focus on flags, Zelewski bullied Abdulgawi to stop flying the red flag of the sultan outside his house; only Zelewski should be allowed to fly that flag. The governor reluctantly gave in on both points, and his humiliation was witnessed by large crowds of revelers. The crowd grew angry. Remember, the people of Pangani already had reason to be upset, and this business with Zelewski was confusing and upsetting. Some folks in the crowd threatened to burn down the homes of some Indian merchants. When a German gunboat dropped anchor in the harbor that night, Zelewski signaled it for help.

On the morning of Eid al-Adha, a hundred German marines landed from the gunboat just as prayers were beginning. Zelewski went looking for Abdulgawi, whom he unthinkingly blamed for the unrest. Zelewski heard the governor was at prayer, so he took his one hundred marines and barged into the mosque, interrupting prayers on one of the holiest days of the year. To add further insult, all hundred Germans wore their shoes inside, and in the chaos one of Zelewski’s hunting dogs got into the mosque. Abdulgawi slipped out the back. Holiday prayers were cancelled. And all the revelers in the streets watched as the sultan’s governor was unable to stop someone who claimed to be the sultan’s representative from defiling the house of God. Then Zelewski opened Pangani’s jail (to show who was in charge now). The jail was mostly full of debtors and runaway slaves, so freeing them indicated that the the Busaids were now either unable to enforce property rights or were now actively opposed to them.

The gunboat and its marines left the next day. The Shirazis anticipated what was coming and left Pangani for their inland estates. Thousands of witnesses spread the news of what they’d seen. Young men streamed in from the hinterlands. Almost all of them were armed. No one was yet sure what was going to happen, but it was clearly going to be big. Zelewski sat in the biggest house he could commandeer and issued decrees that everyone ignored. In September, a ship carrying gunpowder to be traded upcountry for ivory pulled into Pangani. Zelewski didn’t like the idea of further arming people and ordered the ship to depart. Instead, the people of Pangani seized the gunpowder and divided it amongst themselves. Some of the upcountry men wanted to kill Zelewski, but a few Shirazis got to him first, locked him in his house, and posted a guard outside – more for Zelewski’s protection than to keep him imprisoned. Folks tore the sultan’s flag to shreds.

Events in Pangani were now out of anyone’s control. The sultan sent troops to evacuate the imprisoned Germans to Zanzibar. There was no hope of holding Pangani. The revolt spread to other Swahili cities. The Germans were kicked out just about everywhere, and the sultan was powerless to stop it.

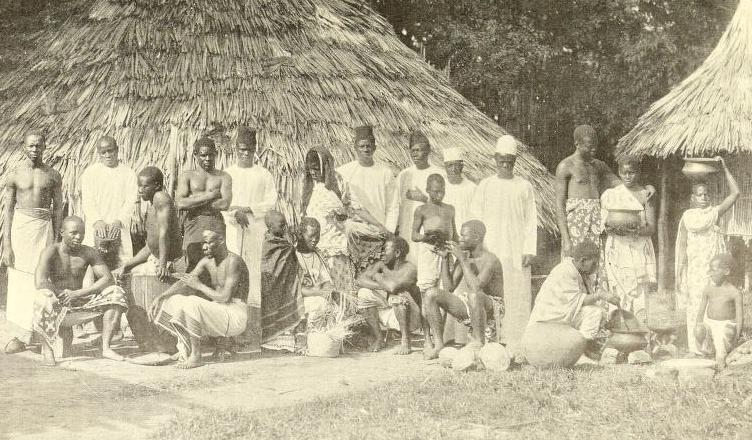

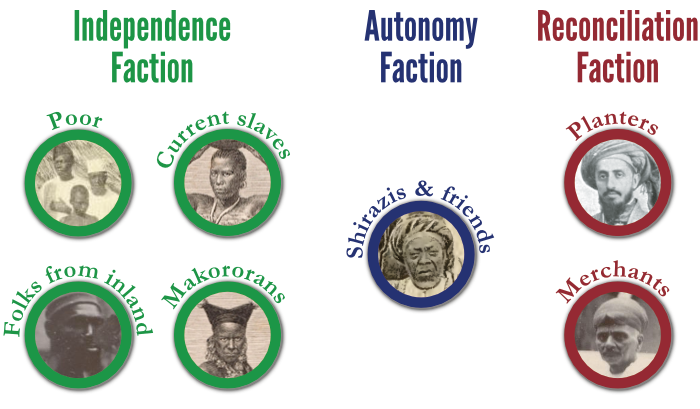

In the days before the revolt in Pangani, we can identify roughly eight groups: Arab planters, Indian merchants, Shirazis, poor Swahilis, immigrants, slaves, self-emancipated ex-slaves in Makorora, and upcountry non-Swahilis just passing through. In post-revolt Pangani, these eight groups coalesced into three factions.

First was a group that sought total independence from Zanzibar. These were people who had never benefitted from Busaid leadership. Most of their ranks were drawn from the enslaved, the poor, the Makororans, and the folks from farther inland. They were far and away the largest faction, but had the least social capital, which made it hard for them to negotiate with outsiders. We don’t know the names of many of their leaders, but we know they were organized and disciplined; they dug fortifications around Pangani and kept them manned 24/7. Remember, everyone was armed.

Next was a group that sought greater autonomy from the sultan, but not total independence. These were people who had benefitted from Busaid rule in the past, but were now paying for it. Most Shirazis fell into this group, as did those who were still loyal to them: many poor Swahilis, many slaves who’d maintained good relations with their owners, and many immigrants. There were also a few elite Arabs in this group. The autonomy faction sought the restoration of Shirazi pre-eminence and the patterns of patron and client that used to keep everything humming. The autonomy faction had the strongest cultural authority.

The third group was the self-described ‘peace party’ that wanted reconciliation and a return to the status quo. These were the Arab planters and Indian merchants. They had the most money and the most religious authority, but the fewest members. Their money also wasn’t terribly useful. A few times they tried importing mercenaries, but the mercenaries usually joined the other two factions pretty quickly.

All three factions were furiously politicking with one another. The independence faction, though far and away the strongest, couldn’t do away with the other two factions, as they needed them to negotiate with the sultan and the DOAG – and to keep business flowing, without which this whole revolt was for nothing. As for the other two factions, their ability to influence events was limited to what the independents were willing to tolerate. For example, the independents blocked the Indian merchants from fleeing Pangani, as Indian credit was the lubricant that kept the wheels of business turning.

The autonomy faction was the first to cave. Their most prominent leader, Bushiri bin Salim (more on him next week) was frustrated by his inability to get the independents to compromise. So he took his loyalists and left Pangani to besiege the Germans elsewhere. Then in the spring, the thousands of upcountry fighters who so strengthened the independents left on trading expeditions inland. This gave the reconciliation faction more leeway than they’d had before. Relations between the reconciliators and the independents were hardly warm, though. Remember that many independents had been worked almost to death on the plantations of the reconciliators. But the independents needed the reconciliators to keep business flowing, so they permitted (and sometimes demanded) the reconciliation faction stay in Pangani and let them speak for the town in negotiations with Zanzibar.

As with most uprisings, it all came to naught. Next year, the Germans returned in force. Berlin hadn’t really wanted any colonies in East Africa, but this revolt had wounded German national pride. The German Army and Navy were dispatched to crush the revolt, which they did mostly by bringing in African mercenaries from elsewhere on the continent, who had no opinions about the merits of the three factions. The British also helped put down the revolt to protect their interests in the Indian merchants. The autonomy and independence parties were both massacred, as was much of the reconciliation faction. The DOAG became German East Africa, the role of the Sultanate of Zanzibar was reduced, and the whole thing was very depressing.

OK, so that was really long. How do we use it at the table?

What we’ve got here is eight groups that, when the chips are down, organized themselves into three factions. You can mostly tell which faction someone will be in based on their group, but not entirely – people are individuals, and the autonomy faction in particular seemed to draw people from across all eight groups. Importantly, the factions aren’t symmetrical. They have different strengths and weaknesses, and one of them is clearly stronger than the other two – yet can’t just kick the other two out, because it still needs them. And all three groups want something easy to understand, yet mutually exclusive with the other two. This is a really cool model for building factions at your table. It makes every faction feel unique and special, yet make sense with the other two.

What’s also really important is that this revolt was probably going to happen one way or another. If the DOAG hadn’t come in and screwed everything up, there would probably have been a different precipitating incident within the next decade. I’m reminded of Green Ronin’s Song of Ice and Fire Roleplaying Game which is set a year before Game of Thrones begins. The setting book’s central argument is that the game world is rotten to the core, no one has any reason to like or trust anyone else, and if your players’ actions cause things to go differently than happened in the books/show, that’s fine because some other event will start the war anyway – probably events your players caused! And that’s what’s going on in Pangani.

When filing the serial numbers off the Pangani revolt to use in your fictional setting (or just picking a few choice details to insert into your campaign), you can have your Zelewski-analogue roll in and make the worst choices. And maybe the party stops him from being so dumb. That’s fine. Have something they did (someone they angered or offended) kick off the revolt instead. Like I said – if it wasn’t this thing, it’d be something else. Depending on how the revolt starts, the groups might align themselves differently from the factions they formed in real life. Then, once the revolt is going, you’ve got endless drama. Everything the PCs want to do has someone they’ll need to overcome to do it, and every action they take necessarily makes them both friends and enemies. It’ll be complicated, messy, and unpredictable – the best kind of gaming!

All this is surprisingly easy to insert into your fictional setting. All you really need is a weak central government – or a government that’s weak in the relevant region – that auctions off much of its administration. Someone new just won the auction, and they’re coming in with absolutely no idea how complicated and messy your fictional town is. You’ve got local elites who are heavily in debt and despise the central government and the bankers it supports. You’ve got lots of different kinds of folks from the margins of society to take the roles of the slaves, freedmen, immigrants, upcountry fighters, and the poor in Pangani. And you’ve got folks who are closely affiliated with the central government but exploiting everyone else – they can take on the role of the planters.

Come back next week when we’ll talk about six political power players from the revolt: two from each of the three factions! Did you notice that I was a little light on the names of actual people in this post? That’s because I’m diving into them next week. So come on back then!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Source: Feasts and Riots: Revelry, Rebellion, and Popular Consciousness on the Swahili Coast, 1856-1888 by Jonathon Glassman (1995)