This is part 1 of an 4-part series about the wars of Julius Caesar. We’ll start with his nine-year conquest of Gaul, then move into the civil war against his former ally Pompey, his involvement in an Egyptian civil war that placed Cleopatra on the throne, and his defeat of Pompeian rump states in Spain and North Africa.

Because this is an RPG blog, my focus is on moments where individual people impacted the outcomes of battles and entire campaigns. The standard advice for doing giant battles at the table is to give your PCs a special task that has a big impact on the fight: assassinate an enemy general, take a particular tower that can be used as a signal post, scout out enemy snipers, etc.

Otherwise, you have to use mass combat rules (which take the focus off the PCs) or play an entire battle on an individual scale (which gets boring fast) or just gloss over the battle (which is anti-climactic). Better instead to play out a scene or two where your PCs attempt something awesome, and their success or failure determines the outcome of the entire battle.

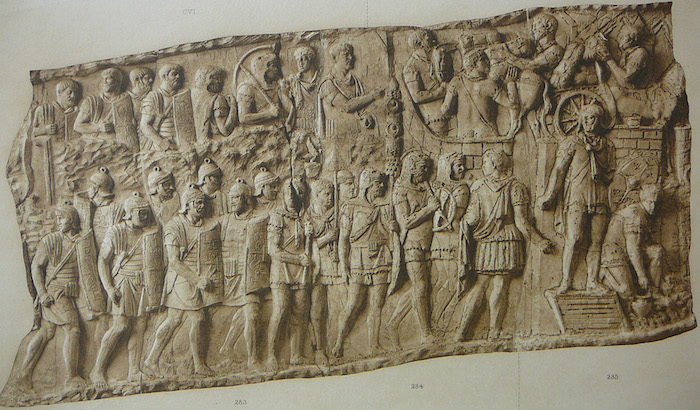

In 59 B.C., 41-year-old Julius Caesar was appointed to the position of governor of Transalpine Gaul – a stretch of southern France, just on the other side of the Alps from Italy. Caesar was already an experienced military commander, politician, and governor of distant lands. The rest of Gaul (roughly modern-day France) was a collection of dozens of independent chiefdoms. The Gauls were a Celtic people with a well-developed warrior aristocracy, a religious order (the druids), and a huge underclass of serfs.

Caesar intended to conquer all of Gaul. Booty from the war would pay his debts, and victories would further his political ambitions. Unfortunately for those ambitions, Caesar had no legal authority to carry out his war. As provincial governor, he had an army, but could only use it in self-defense, unless otherwise instructed by his superiors in Rome. So he exploited a series of crises. Whenever Gauls beyond the border of the province did anything remotely threatening, Caesar invaded. When he couldn’t find crises to exploit, he manufactured them. He would have his conquest, legal restrictions be damned!

One of Caesar’s early excuses to conquer came when some Gallic tribes allied with Rome asked for help dealing with a Germanic king named Ariovistus. The man had carved out a little kingdom for himself in eastern Gaul. If Ariovistus was a threat to Roman allies, he must be treated as a threat to Rome (or so Caesar reasoned). When word came that Ariovistus was moving to take the Gallic town of Vesontio, Caesar quickly moved to get there first.

In Vesontio, the army stopped to resupply. Here, Caesar’s soldiers had a chance to talk to the local Gauls. They heard terrible stories about the Germanic warriors they’d soon face: they were enormously tall, terribly brave, and so fearful to behold the Gauls couldn’t even bear to look at them.

The officers were the first to panic. In the Roman army, officers were political appointees. Junior officers were young noblemen doing a stint in the army before entering politics. They rarely had any military experience. Even senior officers were mostly career politicians who returned to the army for a few years for the prestige. Caesar claims that these men hid in their tents and mourned their fate, certain they would die when they met the Germans.

The panic was infectious. The common soldiers were so frightened their centurions feared they might not march when ordered to. The centurions themselves, all grizzled veterans with decades of service across multiple wars, hid their own fears by claiming they were worried about the impact the dark German forests would have on the army’s logistics. The whole army was on the edge of deserting.

Caesar had to deal swiftly with the panic in the ranks. He called his troops together to address them, and made the arguments paraphrased below.

– Within living memory, a Roman army under Gaius Marius beat back a Germanic army that threatened Italy. Marius’ army was no better than you, so what do you have to fear?

– The Roman army recently defeated Spartacus’ slave rebellion, and Spartacus’ rebels had the benefit of Roman discipline, which the Germans lack.

– The Germans often lose battles agains the Helvetian Gauls, whom you have just defeated. Who should fear such an army?

– Yes, Ariovistus has won a lot of battles too, but only because of his cunning, not his bravery. Those tactics won’t work on us.

– Our logistical position is strong.

– Whenever an army doesn’t obey its commander, it’s because of a major setback or the discovery of criminal behavior on the part of the general. We’ve suffered no such setback, and I am blameless, so I know you’ll fall in when I give the order.

And when the order came to march, all the soldiers did so. With a little quick thinking and some clever rhetorical flourishes, Caesar put an end to the panic.

At your table, your fictional commander might not be around to deal with a sudden, unanticipated panic in the ranks. She might be ill. She might be temporarily recalled to the capital. She might be out on maneuvers elsewhere. Indeed, in your campaign, her very absence may be the thing that triggers the panic! This gives your PCs the opportunity to calm the panic using roleplay, just like Caesar did.

Caesar went on to defeat Ariovistus, but the next year he learned that the Gallic chiefdoms in modern Belgium were organizing to oppose him. That was enough provocation for him, so he marched north. He defeated their combined army, and began conquering the chiefdoms one by one. One of them, the fierce Nervii, gave Caesar particular trouble.

The Nervii used spies to suss out the Romans’ weaknesses. They learned that each of Caesar’s legions had its own baggage train. All eight legions marched one behind another, so each legion’s baggage train separated it from the legion behind. Furthermore, Roman scouts had staked out a site for a future camp at a location advantageous to the Nervii.

The Nervii planned to wait for the first legion to arrive at the site. When the Gauls saw the first baggage train arrive, they’d attack. The first legion would be overwhelmed by superior numbers. The Nervii would slaughter them quickly, plunder the first baggage train, and disappear into the woods before any of the other legions were able to reach the battle.

But Caesar changed his marching order. Because he was passing through hostile territory, he consolidated all the legions’ baggage trains. He put six legions in the front, ahead of the train. The remaining two legions would serve as rearguard. When the Nervii soldiers saw the baggage train arrive and sprang their trap, they faced not one legion but six!

For all Caesar’s cleverness, he still made a fundamental error: he forgot to designate guards when the legions arrived at camp. Normally, while most of Caesar’s soldiers built the fortifications for the night’s camp, a few units would remain armed and ready. In case of attack, they could hold the line long enough for everyone else to gear up and assemble a proper formation. Instead, no one was on guard when the Nervii attacked. So while the Nervii faced a much larger force than they expected, it was also one that was completely unprepared.

It was chaos. Caesar had to get everyone ready for battle, but there was no time to do any of that. There were signal flags to raise, signal trumpets to blow, troops to summon, foragers to recall, a battle line to deploy, and troops to encourage. But Caesar could only do a handful of these things before the Gauls were upon them!

The battle was a very close affair. The Nervii came perilously close to victory. As it was, Caesar still won the day by a combination of tactical flexibility, his subordinates’ initiative, and his soldiers’ extraordinary training. Had any of the three been lacking, Caesar and his eight legions would have perished to a man in grim, distant Belgium.

At your table, if your PCs are close to the general, they may be able to undertake some of the tasks the commander had to omit. Unless your party’s army is as battle-hardened and well-trained as Caesar’s, your PCs had better get those orders out and fast. Lay out as many tasks as there are PCs. Ask who’s doing what. Then throw an obstacle at each PC individually: a surprise attack by a lone enemy scout, a deserting coward spreading fear, a centurion inexplicably gone missing, etc.

The third year of the war saw Caesar split up his forces to wage separate campaigns all across Gaul. In the fourth year, Caesar turned his eyes his farther afield. On a similar justification to his campaign against Ariovistus, Caesar built a bridge across the Rhine and launched a punitive expedition against the Germans. It didn’t accomplish much, but it certainly impressed everyone.

Caesar also planned a expedition against Britain. The British were Celts, like the Gauls, and Caesar claimed they’d provided support to the Gauls that resisted Roman occupation. They had to be punished! Of course, launching the first truly overseas Roman conquest would also be a boon to his prestige and political ambitions.

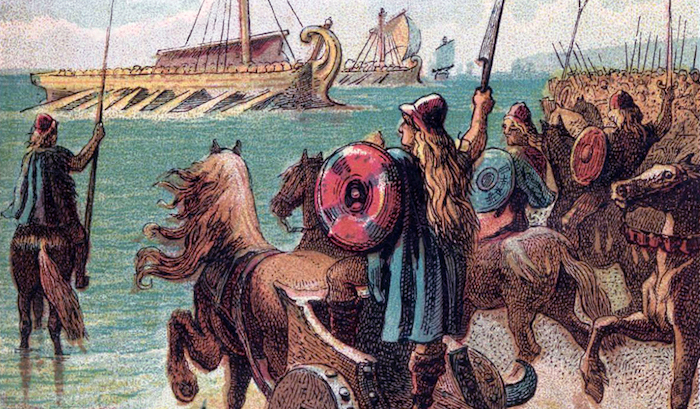

Landing in Britain proved challenging. Romans were poor sailors. Unable to fight the winds and currents, Caesar had to land at a beach where the British were waiting for him. His ships could not beach themselves. Instead, his troops had to jump into the chest-deep water and struggle against the current to reach the shore. All the while, the native Britons fired upon the Roman soldiers and rode horses into the surf to engage them.

Then the standard-bearer of the 10th Legion called out, “Leap, fellow soldiers, unless you wish to betray your standard to the enemy. I, for my part, will perform my duty to the state and my general.” And so saying, he threw himself from his ship into the sea and charged up the beach towards the Britons. The standard was a symbol for the entire legion. It falling into enemy hands would be the greatest dishonor. So the Romans charged up the beach behind their standard-bearer and forced the Britons to withdraw.

At your table, you may want to give a PC a standard as a reward for bravery. Make her earn it. This will make the player value it too. Once a PC becomes a standard bearer, you can start doing vignettes like this one. Present a scene where the standard bearer realizes that the battle may be won or lost in this moment – and ask her what she does. If she bravely uses the moral authority of her standard to save the day, roll the dice to see if she survives. Whether she lives or dies, make it clear that the battle is won because of her.

You can also make the players care more about the standard by having it reflect their accomplishments. For example, in a later update, we’ll talk Caesar’s troops defeating elephants in Tunisia. The legion that requested the privilege of facing down the enemy pachyderms earned the honor of adding the image of an elephant to their standards from then on.

–

When part 2 drops next month, we’ll finish the story of the Gallic Wars with more moments where individual people changed the course of battles and campaigns! In the interim, we’ll have more normal, standalone posts!

–

Source: The Landmark Julius Caesar, a collection of works written by Caesar and his contemporaries, edited by Kurt A. Raaflaub and Robert B. Strassler (2019)