This is part 3 of a 4-part series about the wars of Julius Caesar. Previously, we wrapped up his nine-year conquest of Gaul and began his civil war against his former ally Pompey! This week, we’ll wrap up the civil war.

As before, my focus is on moments when individual people impacted the outcomes of battles and of entire campaigns. The standard advice for doing giant battles at the table is to give your PCs a special task that has a big impact on the fight: assassinate an enemy general, take a particular tower that can be used as a signal post, scout out enemy snipers, etc. Caesar’s wars are full of these moments.

When Pompey fled across the Adriatic in 49 B.C., Caesar lacked the ships he needed to pursue him. So instead, Caesar opted to deal with Pompey’s allies. While they were scattered across the Mediterranean, they were vulnerable. If permitted to flock to Pompey’s side, they’d be formidable. Caesar himself marched to Spain to deal with the enemy legions there. But the city of Massila (modern Marseille) had declared for Pompey, so Caesar dispatched two of his commanders to deal with the situation: Trebonius and Decimus.

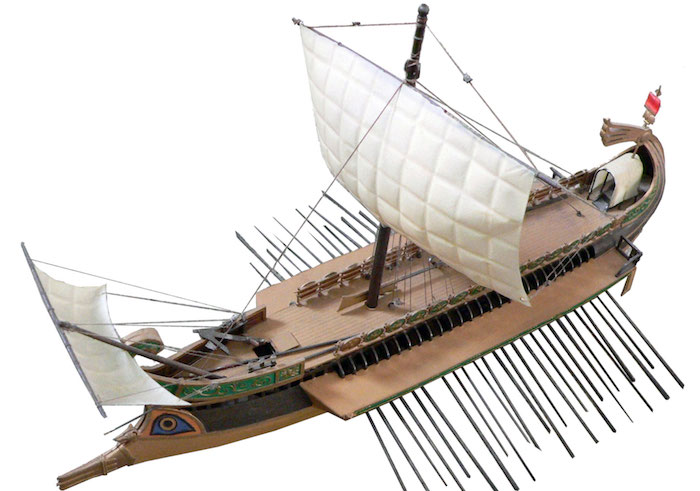

While Trebonius besieged the city by land, Decimus raised a fleet and blockaded it by sea. Massila’s remarkable defenses made Decimus’ fleet the more pressing threat to the city. The Massilans fought two separate naval engagements to try to drive him off.

In the second engagement, the Massilans targeted Decimus’ ship specifically. His flagship flew a red or purple flag. When two Massilan triremes spotted it, they made right for him. Triremes are ships with a large ram and three banks of oars. They tried to ram Decimus’ ship simultaneously, one from each side. But Decimus’ crew were too skilled to be taken like that. With their own oars, they shot forward at the last moment. The two Massilan ships crashed into each other! Both were badly damaged. One had its ram torn off and began to founder. Nearby ships from Decimus’ fleet attacked the two triremes and sank them both.

Decimus carried the day, and Massila soon surrendered. Had he been killed, the outcome of the siege may have been very different.

At your table, if your PCs are the crew aboard a ship inspired by Decimus’, this is obviously an opportunity for a high-stakes helm/piloting roll that can save the day. But regardless of the outcome of the roll, it’s only setting the stage for the boarding action to come! Are the PCs boarding the enemy ships to finish them off, or to escape their own struck and sinking vessel? Both are really fun combats made possible by the success or failure of that initial roll! And both may have a major impact on the overall battle.

Image credit: Rama. Released under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 France license.

The next year, Caesar took his army to northern Greece, where Pompey was waiting. The two would-be emperors moved and counter-moved, forever repositioning their forces so that when battle eventually came, their side would have the upper hand.

150 miles away, forces loyal to Pompey and Caesar were doing the same. Scipio, Pompey’s father-in-law and the commander of two legions, appeared to be marching against Domitius, a Caesarean commander who also had two legions. But it was a ruse! Scipio changed his course and marched on a different Caesarean commander, Cassius, who had one legion of raw recruits and nothing more. Messages detailing this advance reached Cassius, who withdrew as fast as he could, fleeing certain destruction.

To expedite his march, Scipio left behind his army’s baggage and heavy equipment, guarded by 0.8 legions’ worth of soldiers commanded by his subordinate, Favionus. Seeing an opportunity, Domitius marched on Favionus, who sent urgent messages to Scipio. Scipio got the messages, turned around, and reached Favonius just before Domitius did. Ultimately, no serious battle occurred. The real heroes of this engagement were the messengers.

If your party is fast-moving (perhaps mounted, winged, or flying a fast spaceship), carrying messages and intercepting messengers could be a great battlefield task for them. The troop movements in northern Greece are a perfect template for a battle where the PCs perform this role. Scipio will defeat Cassius, and Domitius will defeat Favionus. The victor is not in doubt. What’s at issue is whether each battle happens at all – and that hinges on whether the message gets through.

When the PCs are carrying messages, throw obstacles in their way: wandering monsters to fight, enemy pickets to sneak past, and enemy spies to deceive. When they’re hunting messengers, make it a cat-and-mouse game where the messengers hide their tracks, ride through encampments friendly to them, and sow misinformation amid the bystanders who see them go past. Every obstacle the party overcomes shortens the messengers’ lead.

While Pompey and Caesar chased each other all over northern Greece – a sequence of marches, counter-marches, and battles both consequential and inconclusive – the civil war dragged on elsewhere in the Mediterranean. One of Pompey’s admirals (named Cassius, but not the same guy we talked about above; it’s a common name) sailed against Caesarian-occupied southern Italy. Caesar had two fleets there. Cassius caught one by surprise on the beach and burned it. The second put up a stiffer resistance.

The second fleet was also beached, but defended by a small garrison. These were veteran soldiers too sick to fight, reassigned from units elsewhere to recover on light duty in Italy. Cassius loaded cargo ships with dry wood, pitch, and oakum, set them aflame, and launched them against the beached fleet. A stiff wind carried the flames from ship to ship, and a Pompeian victory seemed certain.

Then the garrison sprang into action. These sick and wounded soldiers pushed through the flames to two beached ships that hadn’t yet caught fire. On their own initiative, they launched the two ships and attacked Cassius’ fleet. They sunk two Pompeian triremes, and captured two large, heavy quinqueremes. One of the quinqueremes was the flagship of Cassius himself, who had to escape in a rowboat.

Then something happened that turned this small victory by a single Caesarian garrison into a large, strategic event. Word reached both sides that in northern Greece, Caesar had just crushed Pompey in the decisive Battle of Pharsalus. Most of Pompey’s army was slain or captured. Pompey himself escaped with only the clothes on his back. When Cassius heard this, he abandoned his campaign against southern Italy. Pompey would need him elsewhere. The sick Caesarian soldiers’ little poke in Cassius’ eye was magnified by distant events into a decisive victory that defended all of southern Italy.

At your table, you can absolutely model an encounter on the sick soldiers’ defiant act. Pushing through the flames to grab a ship and take the fight to the enemy admiral is badass and would make a great RPG combat. But even more importantly, Pharsalus’ impact on this skirmish provides an awesome template for how you can use distant events to magnify the impact of your PCs’ actions. Their small-scale, local heroics can have a big effect if combined with the right news from elsewhere.

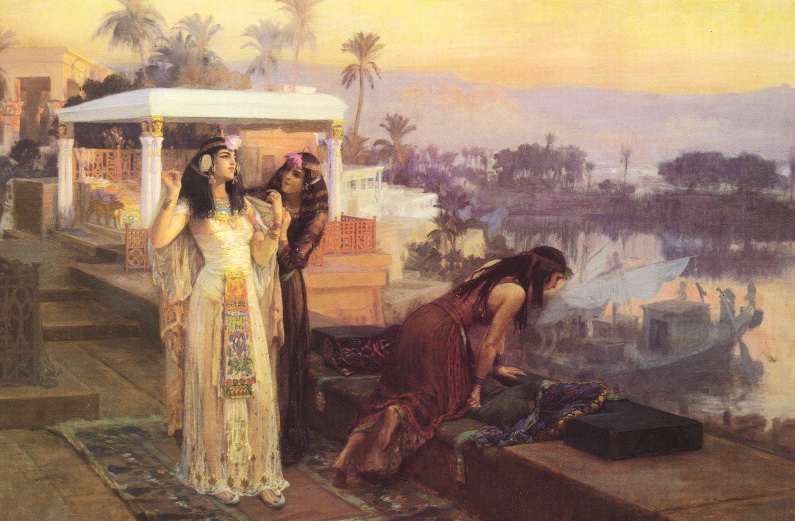

Image credit: Maciej Szczepańczyk. Released under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

After Pharsalus, Pompey fled to Egypt. At the time, Egypt was ruled not by Egyptians or Romans, but by Greeks: the descendants of the army of Alexander the Great. Their boy king, Ptolemy XIII, was an ally of Pompey’s. But when Pompey arrived in Egypt, Ptolemy and his regent betrayed and executed the Roman leader.

Caesar pursued Pompey to Egypt. There, he learned of Pompey’s death through a gift from King Ptolemy: Pompey’s severed head.

Having arrived in Egypt, Caesar found he could not leave. Seasonal, unfavorable winds kept anyone from sailing north. Soon Caesar found himself embroiled in an Egyptian civil war! The war lasted for a year. It prominently featured urban warfare, amphibious assaults, and combined arms in ways few ancient conflicts did. But alas for our purpose here, I couldn’t find any truly gameable battlefield moments! The war ended with Caesar victorious, Ptolemy drowned, and Ptolemy’s older sister on the throne of Egypt: the famous Cleopatra.

When part 4 drops next month, we’ll tell the story of Caesar chasing the remnants of Pompey’s forces all over the Mediterranean! In the interim, we’ll have more normal, standalone posts!

–

Source: The Landmark Julius Caesar, a collection of works written by Caesar and his contemporaries, edited by Kurt A. Raaflaub and Robert B. Strassler (2019)