In 1814, a band of the Sauk Indian nation led an attack on three U.S. Army keelboats on the Mississippi River. The resulting Battle of Rock Island Rapids is an excellent template for a combat encounter at your table. It’s got an interesting geopolitical context (the three-way tug-of-war between America, Britain, and the Sauk), interesting consequences, and all the action takes place at the human scale at which most RPGs thrive, not the battalion-level action that can often fall apart at the table.

This is part eight in a continuing series about PCs on the Battlefield where I look at human-scale engagements where individual PCs can turn the tide.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Joel Dalenberg. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Joel, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

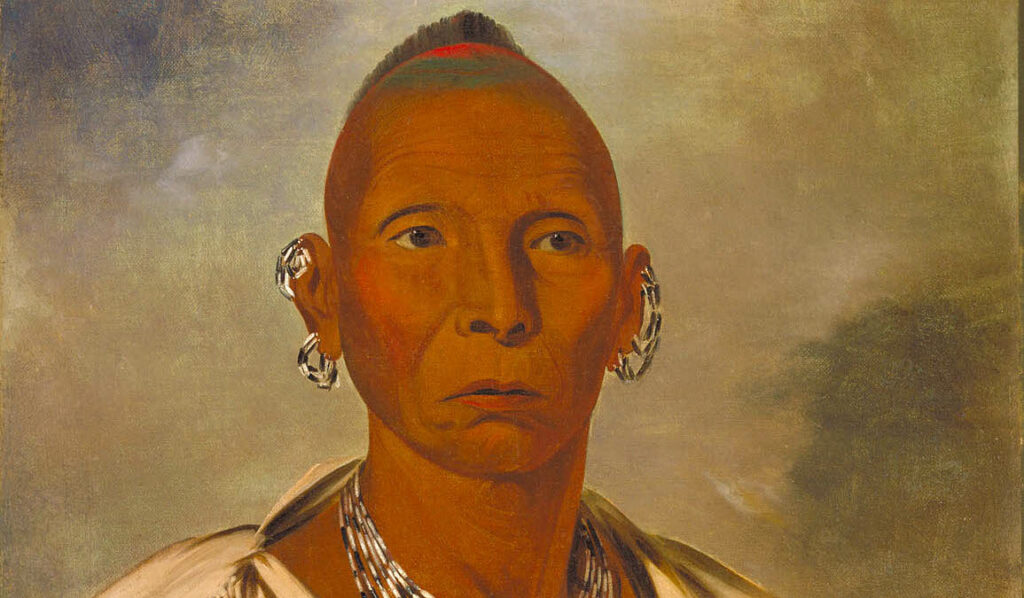

Besides U.S. military reports, our eyewitness source for this engagement is Black Hawk, an influential war leader from the Sauk nation of western Illinois. In the 1830s, he dictated an account of his life, through an interpreter, to a newspaper editor who published it as an autobiography. It became a bestseller. For years, The Life of Black Hawk was one of very few accounts available to the American reading public that presented a Native perspective. The Black Hawk you meet reading his book was deeply principled with how he handled his personal affairs, but more flexible with his politics. He was a skilled fighter and a capable leader, but a poor strategist. The impression you get reading his Life is that of a very scary man with a lot of integrity, but who’s usually in over his head.

In 1812, it was growing clear America and Britain would soon go to war. Both governments began courting the Indian nations in what is today Illinois, hoping to enlist them as allies. Black Hawk faced an interesting choice. He liked the British. They’d always dealt squarely with the Sauk. They kept their promises and, recognizing that the Sauk also kept theirs, let them buy on credit at British trading posts. So Black Hawk’s natural inclination was to lead his band to fight for Britain. But several Sauk chiefs had traveled to Washington where they were told that American traders would start letting the Sauk buy on credit too, as long as the Sauk stayed neutral in the war. Equal privileges without having to fight was too good an offer to turn down. But when Black Hawk’s band visited an American fort, they found the government hadn’t actually transmitted the order to let the Sauk buy on credit. So Black Hawk and his band reported to the British to fight against the untrustworthy Americans.

Black Hawk took 200 Sauk fighters to Green Bay to link up with the British Army. There they encountered an intriguing piece of British propaganda: that America wanted to take the Sauk’s country from them, but that Britain was here to drive the Americans back into their country. From 1812 to 1813, Black Hawk and his men fought for Britain as auxiliaries, helping in a string of failed attempts to take American forts. Black Hawk didn’t care much for this style of fighting, the paucity of plunder, or Britain’s embarrassing defeats, so he led his men home before the war was over.

As the war progressed, it became clear that some of Britain’s propaganda was true: the American government really did intend to drive Indians out of Illinois. The Sauk were split on the appropriate response. One band sought to avoid confrontation by moving west into Missouri and Iowa. Another, led by Black Hawk, chose to stay. They understood America’s intentions, but were skeptical America would be willing and able to go through with them. Consequently, Black Hawk’s band did not involve themselves much in the ongoing war. Black Hawk was sympathetic to Britain, but he’d need a good reason to stick his neck out for his ally. So it was that American boats could sail past Black Hawk’s village unmolested, and even use it as a friendly port.

Specialized boats called ‘keelboats’ were a critical piece of British and American equipment. They were medium-sized (~50 feet long) and powered by sails and oars. They carried troops, supplies, and cannons all over Illinois along the region’s many rivers. Black Hawk’s village of Saukenuk lay at the confluence of the Mississippi and Rock rivers and saw keelboats often. Many were shuttling up and down the Mississippi between the American city of St. Louis and the fort at Prairie du Chien.

In July of 1814, three American keelboats stopped in Saukenuk. They carried 98 soldiers to reinforce the fort at Prairie du Chien. Black Hawk’s band had no quarrel with these particular soldiers and let them come ashore to stretch their legs and chat. The band’s leaders met with the commander of the little flotilla, one Lieutenant John Campbell. The soldiers shared their whiskey with the village. Towards the end of the day, the keelboats continued up the Mississippi and all was well.

That night, Black Hawk received interesting news from a party of Sauk and Iowa fighters coming down the Rock River: the British had taken Prairie du Chien and were requesting help. It was in Black Hawk’s best interest for Prairie du Chien to remain British; the fewer American soldiers near Saukenuk the better. But the keelboats that had left a few hours ago spelled trouble. So Black Hawk rejoined the war. He gathered his fighters and set off overland to catch up with the boats.

Black Hawk caught up with the keelboats at some rapids at what is today called Campbell’s Island. The Americans were sailing upriver with a strong wind. Campbell’s boat was poorly handled. The wind forced the boat ever closer to shore until she ran hard aground. The soldiers aboard her lowered the sail and some hopped out onto the bank to see about pushing her off, but the wind kept her stuck fast. Meanwhile, the other boats sailed past her and left her behind.

Black Hawk and his fighters crept up on the stuck keelboat and opened fire on the soldiers on the shore. Those that survived the initial barrage climbed back aboard the boat. Some aboard her fired through the windows to no effect: they couldn’t see the Sauk in the underbrush. Black Hawk’s fighters now fired on the boat, punching right through the planks and striking the soldiers within. Black Hawk switched from his gun to his bow and prepared a few fire arrows. After two or three attempts, he succeeded in catching the flammable sail, which lay draped across the deck. The fire spread from the sail to the hull. Soon the whole boat was ablaze!

Then the two other keelboats reappeared, sailing downriver to the rescue. One was driven ashore by the wind a hundred yards downstream of Lieutenant Campbell’s boat. The other, commanded by a Lieutenant Rector, threw out an anchor and pulled up alongside Lieutenant Campbell’s blazing keelboat. Campbell and Rector worked together to evacuate the survivors to Rector’s boat. Through this process, Black Hawk’s people kept up their fire and even wounded Lieutenant Campbell while he was passing between the boats. Rector’s boat became so heavily laden the soldiers had to throw most of their supplies overboard to keep water from spilling in at the oarholes. Rector and Campbell proceeded downstream, leaving the third boat behind.

Image credit: John Workman. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Black Hawk shifted his attention to the third boat, still hard aground about a hundred yards downstream of Cambell’s abandoned and blazing keelboat. This boat had a much smaller complement than the other two, but its commander, a Lieutenant Riggs, was canny. He ordered his soldiers to refrain from shooting. This convinced Black Hawk the soldiers were cowed. He ordered his fighters to rush the boat. Then Riggs’ soldiers fired all at once, killing two Sauk – the only Sauk to die in the battle. This drove Black Hawk’s men back long enough for Riggs’ men to take advantage of a lull in the wind, jump out, push off, and retreat downstream after Rector’s boat and Campbell’s evacuees. The final death toll was sixteen dead Americans and two dead Sauk.

Black Hawk’s men boarded Campbell’s abandoned keelboat and put out the fire. They retrieved from it the bulk of the expedition’s ammunition and several barrels of whiskey. The latter of these Black Hawk stove in. The defeated American expedition retreated to St. Louis. The British kept Prairie du Chien. A later American attempt to build a fort downstream of Saukenuk was similarly repulsed.

This affair left Black Hawk’s band in a good position. When the War of 1812 ended, America had no convenient forts from which to pressure Black Hawk’s band into leaving Illinois. Sure, the American governor of St. Louis (famed explorer William Clark) tricked the band into signing a treaty ceding its lands in Illinois by lying about the contents of the document. But America was not able to enforce its deceit until 1831. The keelboat raid bought Black Hawk and his band 17 more years on their land.

At your table, this keelboat raid makes a great template for a battle in your fictional campaign setting. The whole incident takes place at a human scale, where individual decisions by the PCs (like shooting a sail with fire arrows) can have a big impact on the outcome. It might benefit from a little abstraction (treat each boat as a single NPC that can attack multiple times), but fundamentally it requires no special mass combat rules or anything. And it’s broken into separate stages, each of which is interesting: taking the first keelboat that’s run aground, interfering with the rescue by the second keelboat, and storming the third keelboat. As long as each stage moves fast, the variety will help break up a longer combat and make it feel dynamic and fun.

The Battle of Rock Island Rapids is also a great demonstration of how to fold individual engagements into a broader context that makes them meaningful. Rather than fighting for a scrap of ground or vague notions of strategic advantage, Black Hawk’s aim was simple. If the American keelboats got through, his British allies at Prairie du Chien would fall and America would have a staging ground for raids on Saukenuk. If the American keelboats didn’t get through, it would be harder for America to harass the Sauk. At your table, giving concrete consequences for the outcome of an engagement makes it more real to your players. Plus, if you do a good job, the players may even figure out a way to achieve their objectives regardless of the outcome of the battle, which is super fun when it happens!

Check out my book Making History: Three One-Session RPGs! Three awesome historical one-shots with pregenerated characters and a very simple rules system designed specifically for that story. Norse Ivory is a game about heritage and faith in the Viking Age. A Killing in Cahokia is a murder mystery in the Native American temple-city of Cahokia. And Darken Ship is a horror-adventure starring junior sailors on a U.S. Navy warship who wake up one morning to discover they’re alone on a ship that should carry three thousand.

Sources:

Life of Black Hawk or Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak, dictated by himself (2008 edition)

Upper Mississippi Sketches: the Battle of Campbell’s Island by William A. Meese (1904)