In 401 B.C., Cyrus the Younger, the brother of the Persian emperor, decided to seize the throne for himself. He hired a bunch of mercenaries and marched on Babylon, hoping to catch his brother before the emperor could summon his vast armies from the far-flung corners of the empire. Among those mercenaries was a young Athenian cavalryman named Xenophon. Later in his life, Xenophon wrote a history of the mercenaries in this failed revolt: their long march with Cyrus into the heart of Persia, and—after Cyrus’ embarrassing defeat (see post)—the mercenary army’s even longer march back out through what had suddenly become hostile territory.

This is part of a long-running series about PCs on the Battlefield, showing battlefield moments you can fictionalize for your campaign, where a few PCs can make all the difference. Up to now, I haven’t touched much on adventures PCs might have while on the march with an army. Xenophon’s history, the Anabasis, is full of gameable incidents and details that you can drop right into your pre-existing campaign, turning “we march from here to there” into a compelling and meaningful part of an adventure with an army.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks, Arthur—you rock!

Cyrus the Younger was the governor of much of western Anatolia (modern Turkey), which put him on the frontier. That gave him an excuse to raise multiple armies, ostensibly for separate purposes, and he kept them far apart so no one would have cause to realize what a large force Cyrus actually had. Much of his army was regular Persian soldiers, but his heavy infantry was mostly Greek mercenaries. There were a lot of Greeks working as mercenaries in this period. The thirty-year Peloponnesian War had ended only three years prior; that meant a lot of soldiers suddenly out of work, and a lot of exiles from the losing side needing to find work abroad. Xenophon was probably too young to have fought in the Peloponnesian War, but he backed the wrong faction in post-war politics, and consequently spent most of the rest of his life away from his Athenian homeland.

When Cyrus was ready to move against his brother, he recalled his armies from the field and started marching with them east through Anatolia. He had to move fast. He couldn’t hide his actions from his brother forever, but the less advance warning the emperor got, the better Cyrus’ chances. Cyrus also had to keep his intentions secret from his own soldiers for as long as possible. Once they learned their purpose, they’d have good reason to desert. Fighting the emperor of mighty Persia at his center of power was a losing proposition, and he wasn’t likely to be merciful to his defeated enemies.

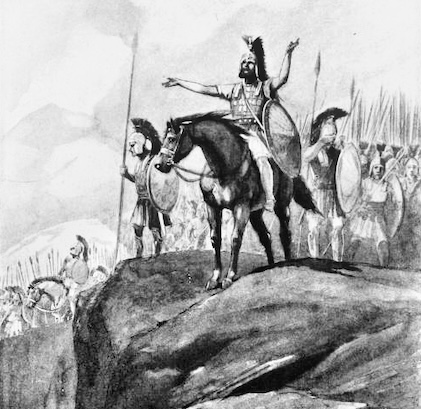

The soldiers figured out what was going on around the time their route touched the sea in southern Anatolia. The mercenaries mutinied and refused to march any farther. One commander, a Spartan named Clearchus, was the first to try to bring them back under control. He called his troops to an assembly. Classical Greeks, even non-democratic ones like Spartans, had a great love for speeches and popular assemblies. He gave a sob story of a speech, about how, as a commander, he was having to choose between loyalty to his troops and his sacred relationship with Cyrus. He made a big show about how torn he was, but how he would always side with Greeks over foreigners, and how they’d better pack up to go home.

While his men (and many others) started figuring out the logistics of going home, Clearchus sent word to Cyrus not to worry, but to give him a little more time. And there was plenty to stew over. The Greeks didn’t have ships, so they’d have to march overland through enemy territory without guides and with Cyrus’ larger Persian force at their backs. There would be no easy resupply. They’d passed through several chokepoints Cyrus could close ahead of them. So when Clearchus called a second assembly, he reminded the Greeks of the difficulties they were already mulling over, then said he’d abide by their decision. The assembly began to quarrel over the right thing to do. Several of the speakers were plants Clearchus paid to speak favorably of returning to Cyrus’ command. The assembly, thus manipulated, decided to go along with Cyrus. They were already too deep into Persia. The only way out was through.

At your table, resolving such a mutiny would be a fun challenge for the players. A fictional character based on Clearchus might ask them to sway opinions in the ranks in much the way Clearchus did with his paid stooges.

As the army marched deeper into the Persian Empire, more gameable events followed.

The army came to the Syrian-Cilician Gates, which present a marvelous obstacle. The Karsos River was the border between Cilicia (north) and Syria (south). The road here went along the seashore, at the base of tall cliffs. And a pair of walls ran along the river, one on each bank, so the road passed through a gate in the wall on the Cilician side, forded the river, then passed through a gate in the wall on the Syrian side. You couldn’t go around these walls owing to the cliffs on one side and the sea on the other, the walls continuing out into the sea. A small force on either wall, thus, could keep a great army from crossing the river. By this point, the emperor knew of Cyrus’s treachery, so Cyrus feared his brother had soldiers on the other side. He loaded some Greek heavy infantry in boats on the Cilician side and sent them around the walls to land far down the beach on the Syrian side and attack the wall from the far side. It turned out there weren’t any defenders, so it was a moot point, but what a puzzle! Put some naval mines or sea monsters in the ocean so that sailing around the walls is perilous, then have a general tell the PCs “find a way to take that opposite wall so the army can keep marching.”

When Cyrus’s army entered Mesopotamia, they found that the royal cavalry was burning the fields before them so they couldn’t harvest food as they went. One of Cyrus’s cavalry commanders offered to hunt down the royal cavalry, but secretly sent a messenger to them offering to switch sides. The messenger was presumably suspicious about this message he was asked to carry, read it, then gave it to Cyrus instead. Cyrus had the cavalry commander arrested, tried, and executed. If you have the PCs serve as the letter-carriers for a similar secret message, you put them in a fun pickle. It’s very suspicious that someone is asking them to carry a message to the enemy. But if they read the message and its contents prove appropriate (maybe negotiating the exchange of prisoners), then they could easily get in trouble. And if they do open it and uncover the treachery, which side do they take it to?

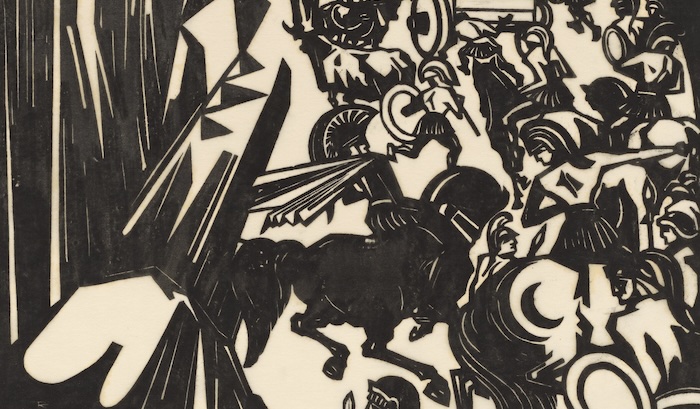

When Cyrus’s army finally met the royal army of his older brother at the Battle of Cunaxa (I wrote about this battle earlier), the usurper Cyrus was slain and his army scattered—except for the Greek mercenaries, who remained intact. The Greeks declined to surrender to the royal army, but opted instead to begin a long retreat to the sea. They couldn’t go back west the way they’d arrived, since they were out of food and all the fields in that direction were burned. So they ascended the Tigris River northwards, hoping to reach the Black Sea. Soon thereafter, a Persian leader in the former rebel army lured the Greek generals into his camp under false pretenses, then had them all poisoned. So the Greeks had to elect five new generals. Xenophon, the young cavalryman and future historian, was one of them. This reconstituted Greek army is often called the Ten Thousand.

As the Ten Thousand made their way north, they were approached by a close friend of the late Cyrus, one Mithradates. Xenophon rode out to meet him, bringing several captains as witnesses. Mithradates asked to travel with the Ten Thousand. Xenophon was initially receptive to the idea. But when Mithradates learned their goal was to march north out of Persia, he gave them a lecture the Greeks found condescending. He said there was absolutely no way to travel through Persian territory without the cooperation of Emperor Artaxerxes. Xenophon suspected then that Mithradates had been sent by Artaxerxes to sow discord among the Ten Thousand. The generals ejected Mithradates and made a resolution that they’d make the rest of the journey without treating with Persian envoys. Within days (or less) Mithradates was back with a unit of Persian slingers, archers, and horse archers to harry the Ten Thousand as they traveled. Such attacks soon became routine, and would persist until the Greeks were out of Persian territory.

At your table, the party might be dispatched to treat with a false friend while on the march. Give the PCs a reason to trust them, but also a reason to doubt them. You want to give the players two motivations to balance when deciding whether to trust this new arrival. Mithradates had been a dear friend of Cyrus, but with Cyrus dead, he had to curry favor with Artaxerxes.

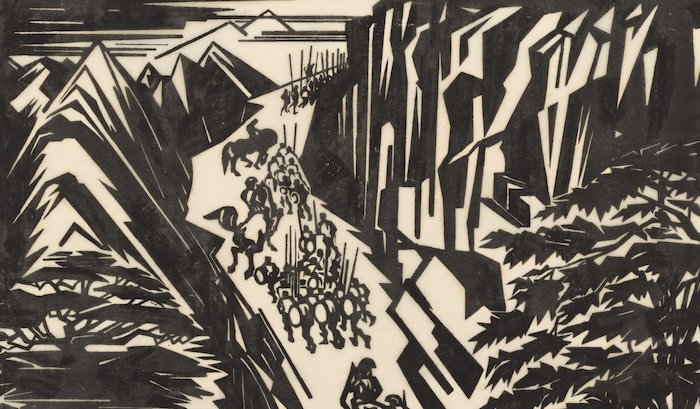

As the Ten Thousand marched through what is today northern Iraq, the Persians kept up their attacks. Two months after the Battle of Cunaxa, as the Greeks passed through the hills north of the Tigris River, one Persian force placed itself on a finger of high ground over the road the Ten Thousand would have to march along. From there, the Persians could attack the Ten Thousand with impunity, blocking the way. But Xenophon noticed a way to drive his enemies off the finger. There was a taller hill near the army that connected to the finger by a ridge. If a small Greek force could get up to the hilltop, it could advance on the Persians while going downhill, giving the terrain advantage to the Ten Thousand. So Xenophon took a few hundred light infantry and set off for the hilltop. When the Persians on the finger noticed the Greeks doing this, they too set off for the top.

It became a footrace! Whichever side reached the hilltop first would be able to easily drive off the other side, which would be attacking uphill. While Xenophon urged his troops on from horseback, one of the light infantrymen, somewhat justifiably, complained about it. “Xenophon, you’re up on that horse, and I’m down here on foot lugging this shield.” So Xenophon, like a good officer, leapt down off his horse and took the soldier’s shield from him, then continued running on foot. But Xenophon was also wearing a metal breastplate, so he tired and began to lag behind. So some of the other infantrymen mocked the complainer and threw things at him until he took his shield back. The Greeks reached the hilltop before the Persians. The Persians didn’t even bother contesting it, but departed the field. The Ten Thousand were thus able to continue marching north.

At your table, this footrace makes a great template for some sort of skill challenge or contest. It’s a battle without actual combat!

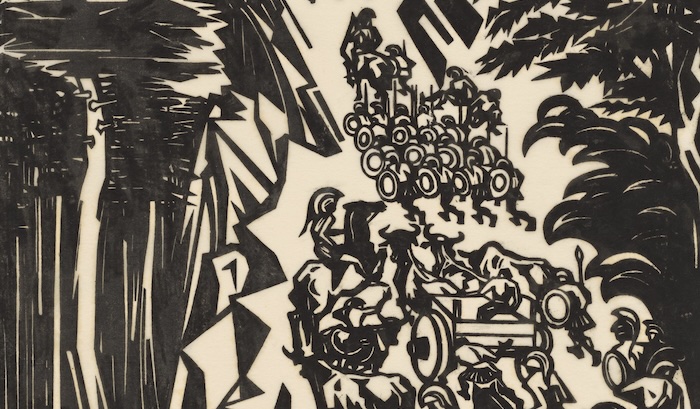

As the Ten Thousand entered the mountains of what is today southeastern Turkey, they passed out of Persian control. While Persia claimed as subjects the peoples of the lands around, the mountains were the home of the Kardouchoi, who remained free. For the Ten Thousand, the Kardouchoi would be the first of many peoples who would see this army entering their lands and see it as an invading enemy. The Ten Thousand did little to alter this perception, for lacking food, they had to pillage the stored winter grain from the villages they passed. So while neither side knew the other, they were enemies out of necessity.

After fighting their way through the narrow mountain passes, the Ten Thousand came to the valley of the Kentrites River. The Kardouchoi massed in the mountains behind them. Waiting on the other side of the river, daring the Ten Thousand to cross, was a Persian force. The river was shallow enough to ford, but deep enough for it to be hard work. The Persians would kill them all with arrows and slingstones before any Greeks reached the bank. It was a custom for Greeks on campaign to frequently perform animal sacrifices and read the omens. And despite the bad situation the Ten Thousand found themselves in, the omens were positive.

Soon, two Greeks out gathering firewood saw something useful. They watched a group of locals—an old man, an old woman, and some girls—go down to the river in a place where the crags ran right down to the water. The Greeks tried the place and found the water was not even waist high there. Furthermore, with it being so rocky, the Persians couldn’t bring their cavalry to that spot. The Ten Thousand marched on the secret ford and made additional sacrifices. Finding the omens good, they crossed. It took some fancy maneuvering and a little deception to get the whole army across safely. Indeed, mid-crossing the Kardouchoi came down from the heights to attack the retreating Greeks. But once the Ten Thousand were across, the Kardouchoi didn’t pursue and the Persians quit the field.

At your table, an opposed crossing like this one (with another enemy at your back to provide an imminent threat) is an opportunity for the party to go scout for something that might save the day, like this secret ford. They might come upon some locals and choose to either follow them in secret or ride up and sweet-talk them. Even if they get nothing directly from the locals, the party might find evidence of regular activity that reveals a local secret. And there’s also the matter of the omens. In a campaign with magic, PCs reading omens might reveal all is not lost.

On their way from Persia to the Black Sea, the Ten Thousand passed through more lands. They still had to eat out of local food stores and had no money with which to pay for that which they took. Some tribes offered food and guides as a gift to speed the Ten Thousand on their way. Others harried and fought them, to no avail. In the land of the Taochoi in what is today northeast Turkey, the Greeks found most of the villages too heavily fortified to plunder. But they found one village that they thought weak enough they might take it. Being out of food, they had no choice but to attack.

The village was atop a rock outcrop, with only one way up from the valley floor to it. If you made it up the path to the top, the village had no walls or gates to stop you from entering, and no armed defenders to bar the way. What the villagers did have were boulders they could push over the cliff to come crashing down on those ascending the path. By the time Xenophon reached the place, many Greeks had already had their legs broken by falling rocks. But the attackers noticed that only 150 feet of the path could be targeted this way, and of that 100 feet was protected by stout pines. As long as men moved swiftly from tree to tree, they were only exposed to danger for a single 50-foot stretch.

Then the day’s duty captain, Kallimachos of Parrasia (in the western Peloponnese) began a clever ruse. From behind the tree closest to the village, he’d dart out along the path. When the defenders pitched a cartload of boulders down at him, he rushed back to safety. This he did several times to exhaust the villagers’ supply of stones. Kallimachos was part of a gang of friends who often competed with one another to perform the most valorous deed on the battlefield. When his friends saw what Kallimachos was doing, they were afraid he’d be the first to enter the village and gain all the glory. So they raced up the path to overtake him. The lot of them, Kallimachos included, ran pell-mell up the 50 exposed feet and entered the village in a confused muddle, and there were no further stones thrown down. Instead, the villagers started jumping off the cliff to their deaths. This was unusual enough for Xenophon to comment on it in horror, but it wasn’t unreasonable. The Ten Thousand didn’t just take food from captured villages, they often enslaved those who resisted them, intending to sell them when they reached the Black Sea.

At your table, while your party is hopefully not interested in doing what would today be a war crime, the business with the boulders on the path is super gameable. Set up a situation for your army akin to that of the Ten Thousand: needing something (like food) accessible only in this queerly-fortified village, and with glory and advantage to the people who first reach it. Set it up so every time boulders come crashing down there are fewer of them. This makes it worthwhile to use up the defenders’ supply of stones. But at some point an NPC may chance the crossing, so the party doesn’t want to use up all the stones before they cross. It becomes a push-your-luck game! How many times do you want to make the path safer (and therefore better for your rivals too) before you hazard the crossing?

Northwest of Taochoi lands, the Ten Thousand stumbled upon an overlook that gave them their first view of the Black Sea. To reach the sea, they’d have to cross the lands of the Makrones, who indeed came out in battle array to oppose them. But the Ten Thousand had a stroke of luck. One of their light infantrymen was a freedman, who’d been a slave in Athens, dragged there from his native land. He recognized the language the Makrones were speaking: it was his native tongue! Completely by accident, he’d come home. He told the generals this and offered to translate. Thanks to this translator, the Makrones and the Ten Thousand were able to come to an agreement. The Makrones helped the Ten Thousand on their way, and sold the Greeks food, purchased with spoils looted from (and since) the Taochoi. Xenophon does not record whether the light infantryman stayed behind with his people.

At your table, one of the PCs could serve in a role akin to that of the light infantryman. If any PC knows an obscure language, a scene like this is a great way to give her some spotlight time. It doesn’t even have to be the language spoken by everybody in the territory the party’s army needs to pass through. As long as two locals can be overheard speaking the obscure language, you have the opportunity for a PC to serve as a diplomat. You could even have the NPC interlocutors be family members of the PC, who are similarly traveling a long way from home.

After seven months of hard travel, the Ten Thousand finally reached the Black Sea. Here they were at last among people whose language and culture they shared. The city-states of Greece had long foundied colonies on the Black Sea. But while the Ten Thousand were no longer on daily marches under constant attack, they weren’t home. They posted up in the culturally-Greek city of Trapezus (modern Trabzon). The Ten Thousand debated internally whether they should march overland to the Aegean Sea or charter ships to take them to Greece. It would take a while to gather enough ships, but the Ten Thousand were truly sick of walking. While this debate occurred, Xenophon quietly made arrangements for walking. He pointed out to the leaders of Trapezus (who dearly wanted the Ten Thousand gone) that the roads west out of the city were in bad shape. If the city would pay to repair them, it might speed the Ten Thousand on their way. And indeed when it proved impossible to gather enough ships, the Ten Thousand marched on those repaired roads west out of Trapezus.

At your table, pressuring city leadership to improve the roads the party’s army will later march along could be a neat scene.

It’s hard to tell where to end the story of the marching Ten Thousand. As the army made its way west along Anatolia’s Black Sea coast, it repeatedly found itself enmeshed in regional politics. Representatives of far-off Sparta, in this brief moment Greece’s most powerful state, didn’t want the mercenary army returning to Greece. Persia didn’t want the army to remain in Asia. And local rulers tried to use the Ten Thousand to advance their own interests, often successfully. Meanwhile, many troops were finding new employers, chartering individual passage back to Greece, or settling near the Black Sea. Xenophon chose to end the story abruptly when Sparta hired the Ten Thousand (now more like five thousand, with Xenophon at their head) for another war into Persian-controlled Anatolia.

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Bluesky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social. On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp.

Check out my book Making History: Three One-Session RPGs! It’s three awesome historical one-shots with pregenerated characters and a very simple rules system designed specifically for that story. Norse Ivory is a game about heritage and faith in the Viking Age. A Killing in Cahokia is a murder mystery in the Native American temple-city of Cahokia. And Darken Ship is a horror-adventure starring junior sailors on a U.S. Navy warship who wake up one morning to discover they’re alone on a ship that should carry three thousand.