In July, 1861, the U.S. merchant sailing vessel S.J. Waring was seized by Confederate pirates. William Tillman, a black man and the ship’s cook and steward, learned the pirates intended to seize him too and sell him into slavery in the Confederacy. Tillman was not going to let that happen. He spent nine days quietly preparing, then sprang his trap. He personally killed three Confederates, took control of the Waring, and sailed her to Union territory and a hero’s welcome. It’s one heck of a story, and it’s a great model for an adventure in your ongoing RPG campaign.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

July of 1861 wasn’t a great time for merchant ships sailing under the U.S. flag. Lincoln had been elected eight months prior. Fearing he would abolish slavery, seven southern states declared they were seceding from the U.S. before Lincoln was even inaugurated. Others would follow, and the Civil War soon began in earnest. The newly-declared Confederate States of America didn’t have a navy to speak of. So it turned to the tactic that weaker maritime powers usually adopt when going up against stronger ones: attacking the enemy’s unarmed commercial shipping. The Confederacy commissioned privateers: pirates who attack the merchant ships of the enemies of the nation that sponsors them. Privateering was passé by this point – the great powers of Europe had even signed a compact agreeing they wouldn’t use the tactic anymore – but the constitutions of the USA and the CSA both authorize the commissioning of privateers. Confederate true-believers and the greedy alike volunteered to mount cannons on their ships and go murder and plunder on the high seas – as long as they only attacked U.S. ships.

There are some people who see privateers as fundamentally different from pirates. I’m not one of them. The murder of unarmed civilians and the theft of their cargos remains murder and robbery regardless of whether you’ve got a fancy piece of paper. The only practical difference is that a privateer has a smaller pool of potential victims. And legally – at least under U.S. law – Confederate privateers were simply pirates. The U.S. didn’t recognize recognize the Confederate States of America as a separate, sovereign nation. That meant the CSA had no more legal right to commission privateers than did a neighborhood knitting circle. Some captured Confederate privateers were successfully tried for piracy in U.S. courts – a hanging offense! However, none were ever actually hanged because of the one arena in which pirates and privateers are definitely different: diplomacy. The CSA made clear that it considered captured Confederate privateers to be lawful combatants who should be treated as prisoners of war. If the U.S. hanged them for piracy, the Confederacy would retaliate by hanging some Union POWs. So captured Confederate pirates were shuffled off to POW camps rather than hanged.

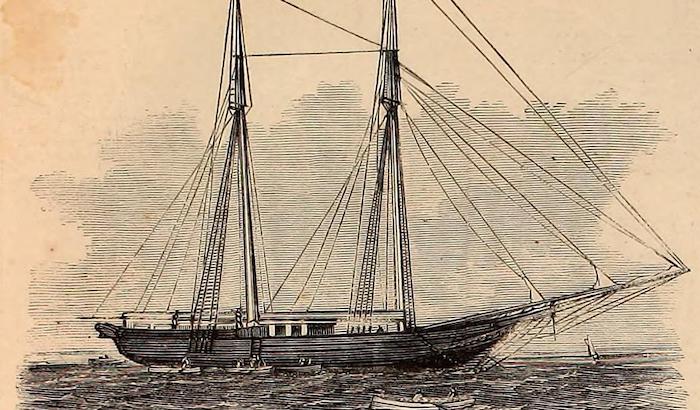

The Waring was a two-masted schooner 119 feet long and 19 feet wide. She was on the smaller end for a ship engaged in international trade, but her schooner-rig sail plan let her operate with a small crew, keeping costs low. Waring departed New York on July 4th bound for South America. As she was setting off, so too was the Confederacy’s first batch of pirates. Waring’s crew had no way to know the danger they were in.

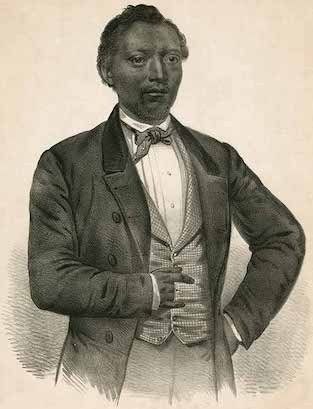

There were nine men aboard Waring: three officers, four sailors, one passenger, and the ship’s cook and steward, a black Rhode Islander named William Tillman. He’d been born free, though many people in Rhode Island were enslaved. He’d worked at sea his entire adult life. Tillman prepared meals and cleaned up after the officers and the passenger. When needed, he’d man the helm, furl, hoist, reef, and row alongside the rest of the crew.

As the Waring proceeded towards South America, the Confederate pirate ship Jefferson Davis scoured the sea lanes on her maiden voyage. She was a two-masted ship with square-rigged sails of brown hemp canvas in the French style, rather than the more common white cotton canvas. Her hull was painted black and stained with rust. She flew a false flag (French) to let her creep up on her victims. She had four cannons and a swivel gun concealed under tarps on her deck. She had a history, too. Under the name Putnam, she’d illegally transported enslaved people from Africa to sell in the American South; while slavery had been legal at the time, the transatlantic slave trade was not. Putnam had been caught by the authorities and her human cargo was shipped to back to Africa, but they were dispatched to a totally different part of the continent from whence they’d come, and half of them died of disease in the time they were away.

The captain of the rechristened Jefferson Davis was a Nova Scotian immigrant and true believer in the Confederacy named Louis Mitchell Coxetter. Captain Coxetter wasn’t much of a sailor; he got his position because he was one of Jefferson Davis’ twenty-seven joint owners. Much of the decision-making was probably done by the ship’s first mate, William Ross Postell. Postell was a capable seaman but quarrelsome, hard-drinking, and hard to get along with. He’d spent eight years in the U.S. Navy, then joined the navy of the new Republic of Texas. The Texans threatened to discipline him for bad behavior and didn’t pay him as much as he wanted, so Postell went into private practice, even working aboard a different ship involved in the African slave trade. The rest of the pirates were a motley mix of the poor, the desperate, and the true-believing.

The two ships encountered one another on July 7th, 1861. After one warning shot from the pirates’ swivel gun, Waring’s captain let them aboard. It sure beat letting the Jefferson Davis sink the schooner, for Waring had no cannons and could not outrun the Davis. The two captains knew each other; they’d both worked in the southern shipping lanes and had bumped into one another a time or two before. So while the pirates scoured Waring’s hold for anything worth carrying off, the two captains shared a bottle of brandy. The pirates restocked their supplies from Waring’s stores, taking whatever guns and tools they could find. Then it was time to turn Waring into a prize. Five of the Waring’s crew – the three officers and two of the four sailors – were taken aboard the Jefferson Davis, and an identical complement of pirates was transferred from the Davis onto the Waring. This meant the schooner still had enough hands to sail her, but now the pirates outnumbered the original crew, and could compel them to sail her to an unspecified southern port where the ship and her cargo would be sold. Remaining aboard the Waring were William Tillman (the steward), a German sailor named William Stedding, a Scottish Canadian named Donald McLeod, and the ship’s sole passenger, an Irishman named Bryce MacKinnon, who’d been bound for Montevideo.

Being part of a prize crew bound for a southern port was an existential threat to Tillman. Before the Jefferson Davis departed, Captain Coxetter told Tillman that he should report to Coxetter’s estate – with the implication that he would join Coxetter’s enslaved staff. Within a day of Davis’ departure, Waring’s three new Confederate officers spoke openly about taking Tillman to the auction block in Charleston and splitting the profit from his sale.

Tillman did not accept this fate. He took stock of the situation and sussed out whom he could trust. MacKinnon, the passenger, was out. He’d struck up a friendship with the pirates on the prize crew, and might reveal Tillman’s plans. Tillman didn’t get far with McLeod, the Scottish Canadian. McLeod and MacKinnon were both citizens of the United Kingdom, which was friendly to the Confederacy. McLeod was confident the British consul would look after him. Tillman had more luck with Stedding, the German. Stedding was worried the Confederacy would draft him into their navy and make him risk his life fighting the U.S. against his will. Stedding wasn’t in nearly as grave of danger as Tillman, but he was willing to take some risks to free the ship. Stedding had on him a pistol the pirates hadn’t found. Tillman had hidden in his berth a hatchet, placed there long before anyone had seen the pirates. It was a useful tool aboard ship.

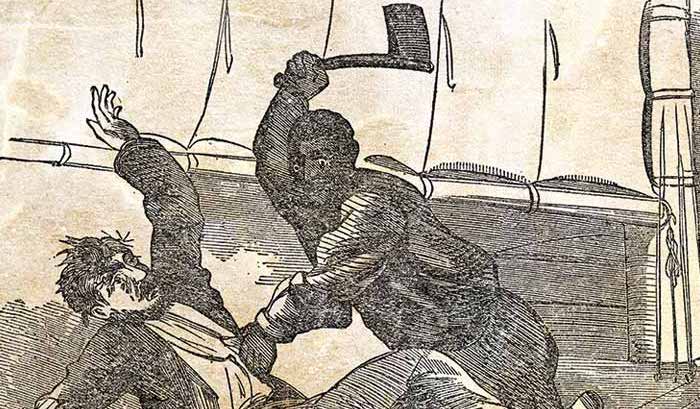

On the night of July 16th, Tillman and Stedding acted. The only people who were supposed to be up and about were Stedding (at the wheel) and the Confederate first mate (supposedly keeping an eye on things, but really sleeping up on deck). When Stedding was confident he was the only one awake, he took off his boots (to move quietly) and went below to the shared common area that all the cabins opened into. He roused Tillman, then retreated back up to the ship’s wheel. Tillman crept to the cabin of the prize captain and struck him in the head with the hatchet. The captain gasped and made faint, pained noises. Tillman strode to the second mate’s cabin and did the same to him. Then he turned around and saw MacKinnon, the passenger, roused by the noise and gawking from the door of his cabin. “Sir, you needn’t be scared,” Tillman said. “I suppose you know what I am doing.”

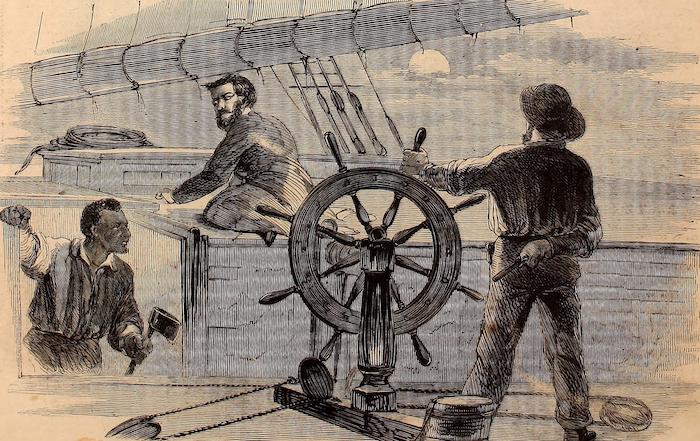

Up on deck, the first mate had woken up to find Stedding training a pistol on him. Tillman emerged on deck and gestured at Stedding not to fire. The noise would awaken the two remaining Confederates. Instead, Tillman attacked the first mate with the hatchet. Stedding and Tillman threw the mate’s bleeding body overboard. Then they went below and did the same with the second mate and the captain. All three were still alive when they hit the water. Now the last two pirates emerged on the scene. Tillman didn’t kill them. “We have done all the butchering I guess we shall do this voyage. Those two fellows I intend to take back. There is two of them and there is two of us. I guess we can manage them pretty well without taking their lives.” The ship’s steward was now in command.

The five men still aboard had to work together to get the ship back to a Union port. None of them had much knowledge of navigation; that had been the job of the slain officers. The two pirates were kept shackled except when they needed to be free to work. Tillman wasn’t going to let them do what he’d done. Later in the journey, it was revealed that Stedding’s pistol couldn’t actually shoot. Convenient, then, that they’d not had to use it. The Waring reached New York on July 21st.

Tillman was a hero! The press loved him. The date of the Waring’s return coincided with the first major battle of the Civil War (First Bull Run), which was a Union defeat. Tillman’s victory was a balm on that sore. A court ruled that Tillman’s actions constituted maritime salvage, since he saved the ship and her cargo. The court ordered Waring’s insurers to pay Tillman $7,000, Stedding $6,000, MacKinnon $3,000, and McLeod $1,000. After the media frenzy, Tillman kept a low profile. There is no evidence he served in the Civil War. With his newfound wealth, he could afford the fee to opt out of the draft. We know he continued working at sea, married, had a son, divorced, and moved to San Francisco.

At your table, the tale of Tillman, Stedding, and the schooner S.J. Waring obviously makes a great adventure. The PCs are traveling by sea (or by spaceship) and are intercepted by a pirate ship with vastly superior firepower. The ship’s captain makes the smart call and surrenders. Crew are swapped about, and the PCs (whether passengers or crew) are left on their original vessel as part of the new prize crew when the pirate ship leaves. It’s up to the party to quietly organize the rest of the crew and lead the revolt against the pirates.

This story also makes a great starting point for an adventure in Shanty Hunters, my award-winning TTRPG about collecting magical sea shanties in 1880. The Waring remained in service into the 1880s. In a Shanty Hunters game, you’d better believe the ghosts of those three dead pirates still haunt the ship. When the PCs sail aboard the Waring and get tangled up in the magic of the shanty Roll, Alabama, Roll, the pirate ghosts are suddenly empowered to get their revenge! Conveniently, the ship Alabama in that song is also the conclusion of the Confederate piracy story. Only a dozen ships ever signed on as privateers, and they only ever captured twenty-seven prizes. The Confederacy abandoned privateering as a tactic, instead escalating by commissioning commerce raiders: proper warships in the real Confederate Navy going out and sinking unarmed merchant ships. CSS Alabama was the most famous of these pirates in uniform.

–

Source: The Rest I Will Kill: William Tillman and the Unforgettable Story of How a Free Black Man Refused to Become a Slave by Brian McGinty (2016).