The Hêliand, composed about 830 A.D., is a tale of the life of Christ in the Old Saxon language. It takes the form of an epic poem, a saga in verse, and was part of a missionary effort to convert the Germanic, early Medieval Saxons from the worship of their ancestral gods to Christianity. It’s a remarkable text. In an attempt to better appeal to a Germanic audience, the Hêliand’s author makes some changes to the life of Christ as presented in the gospels. What changes the author was willing to make—and those they were unwilling to make—are absolutely fascinating. I close with an RPG adventure hook or extended puzzle that would be a lot of work for a GM and that some players would detest—but for GMs and players who’d be into it, I bet it would be amazing.

Fair warning: this post assumes a fair bit of knowledge about the gospels. You should be able to pick most of it up from context, but some readers may feel a bit lost. It’s also a straight-up textual analysis that takes a long time to get to “and here’s how you can use it in roleplaying games”. I hope you’ll still find it worth reading, but this definitely reads more like an undergrad paper than an RPG blog post. Sorry about that.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

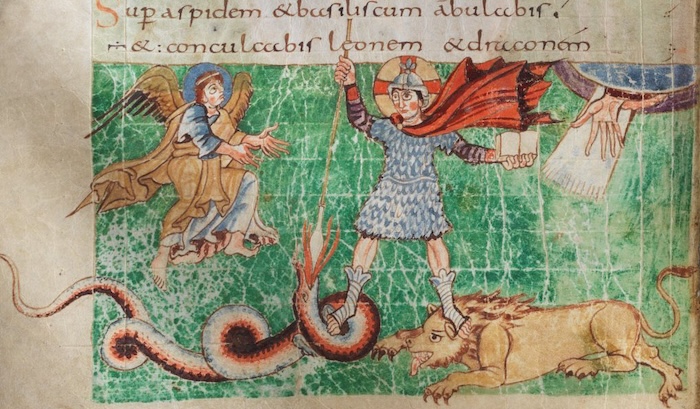

The Hêliand was part of the ongoing Christian evangelical effort in early Medieval Germany to convert those Germanic peoples who, while conquered by Christians, had not yet been convinced to abandon their ancestral gods. The unconverted were strongest among the Saxons: a confederation in northwest Germany. A different group of Saxons had conquered and settled in England, and those Saxons were by then thoroughly Christian. The old Saxons, back in Germany, had been conquered by a neighboring Christian kingdom by 785 and beaten into submission by 804. But many of the ordinary people were not yet convinced by this whole “Christianity” thing. Widespread conversion of the Saxon population was hard. Missionaries—even English Saxons—found that a message of peace, humility, and subordination to God ran exactly counter to the Saxons’ ethics that prized reputation, skill at arms, and personal glory so very highly. To convert them, the missionaries had to meet the Saxons where they were.

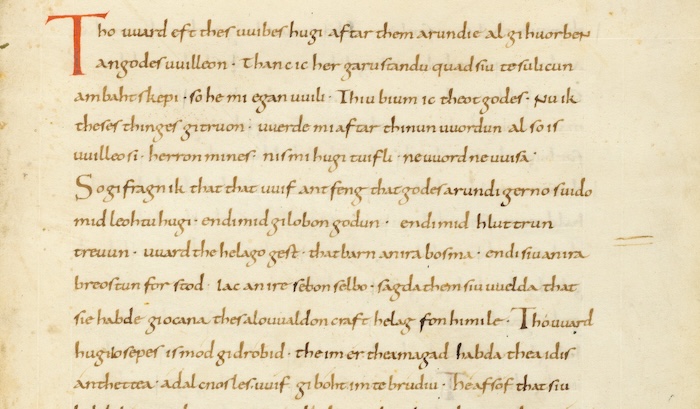

The Hêliand was part of that missionary effort. It turned the life of Christ into a Germanic-style epic, while striving to remain theologically accurate, a goal that could not always be met. The text is in a meter intended to be recited, as were all the epic stories the Hêliand’s audience eagerly consumed. The text is often alliterative (containing strings of words beginning with the same letter), but not always. When the text has to choose between alliteration and using the right word in Old Saxon to convey a theological point, it chooses the latter. Certainly this text was for converts and the unconverted. But it may also have been for the committed: Saxon monks, nuns, and priests who preferred a version of their faith that resonated with them more than the dry texts of foreigners.

Many details in the Hêliand were reframed for a Germanic audience. Everyone of consequence is described as a warrior. The three magi are “war-men from far, far away.” The disciples are “word-wise warriors”. They’re also called “vassals”, “heroes”, and “war-men”—though they do remarkably little heroic warring, restricting themselves to the acts of service depicted in the gospels. And there are occasional references to Germanic religion. Jesus’ vague statement that Judas will regret betraying him becomes a warning about the norns: “For he shall perceive them, the Weird/Fated Sisters, and shall see the end of his care.” The world of the living is “mid-world,” which, sure, is a reasonable description of the universe between Heaven and Hell—but really “mid-world” is Midgard.

The beginning of the piece turns Christ into a chieftain who boasts and about whom much is boasted:

So were those four [gospel-writers] to inscribe with their fingers

Set down and sing and say forth boldly

That of Christ’s might and His strength much had they heard

And seen indeed, which He Himself had here spoken

Proclaimed and accomplished miracles countless

The audience would have no reason to care about Jesus’ ancestry as part the house of David. Nor would they have much patience for a hero of humble origins, born in an oxen stall. So when Joseph and Mary travel to Bethlehem and Mary gives birth, Joseph is a hero traveling to his ancestral family castle, with nary a mention of there being no room at the inn:

So to his homeland

Came Joseph, the good man, as God the Almighty

The Wielder had willed it, with his family he came

Sought his shining castle, his lordly seat

The bastion at Bethlehem, where they both did dwell

Hero and holy maid, Mary the Good

The shepherds watching their flocks by night become warriors guarding war-horses:

Grooms were they there, keeping guard outside

Were war-men on watch; with the horses they were

With the beasts in the field. And lo: before them they saw

The darkness divide in the air. Down came God’s light

Through the clouds came shining, surrounding the grooms

Afar in the fields. And sorely they feared

These men, in their minds. Then God’s mighty angel

They saw coming afar. To them together he spoke

The Olivet Prophecy—in many Christian traditions, one of several Biblical descriptions of the apocalypse—seems to have been reworked to make it more similar to Germanic traditions of the end times (Ragnarok etc.). Nothing in the Hêliand’s version of the Olivet Prophecy contradicts the gospels, but it omits details in ways that change the prophecy’s impression. The gospels’ war of all against all is simplified in a way that permits the audience to see it as a war of two sides, akin to monsters going to war against the gods. The stars falling from the sky and the moon going dark have been moved from explicitly the end of the events to the beginning of the prophecy with no mention of when this will happen chronologically. The prophecy’s parable of the budding fig tree, which suggests this apocalypse is imminent, is sanded down into a form that shifts the prophecy into a vague and undetermined future. All these changes are consistent with what we know of traditional Germanic beliefs about the end of the world.

But it’s interesting the things that don’t change. I was expecting the flight to Egypt to be more heroic somehow. Maybe aged Joseph would have to fight his way to Egypt, leading Mary and the holy child along a road paved with the skulls of their enemies. But it’s very straightforward. “Slime-mouthed” Herod is jealous of the new king and orders all the babies born in Bethlehem killed. An angel of God warns Joseph, and the holy family absconds to Egypt ahead of Herod’s killers who “behead with their hand-strength so many a babe, bairns born in Bethlehem.” Reframing this flight in a way that might have been appealing to a Saxon audience would have risked spoiling the message, so the author makes little attempt to do so.

While the Hêliand author tries sometimes to make the life of Christ appealing to a Germanic audience, sometimes the author sticks to their guns about what Christ is supposed to be all about. You can see this in the epithets the author uses to reference Jesus. Many are things a Saxon warrior would want to see in his liege: Might-Wielding Christ, Ruling Christ, Finest of the Folk-Leaders, Counselor of Clans, the Rich Lord, Strongest of Kings. But Jesus is also the All-Nurturing Christ, the All-Saving Christ, and the Shepherd of Lands—unadulterated Mediterranean Christianity that isn’t necessarily appealing to a Saxon audience.

You see a straightforward example of the tension between audience and message when Peter cuts off the ear of the arresting officer Malchus at Christ’s arrest—the most notable act of violence in the gospels by anyone on Team Jesus. In the gospels, this is played up as an act of foolishness on Peter’s part, proof that he still doesn’t understand that Christ has to be sacrificed and that fighting isn’t the point. “All who live by the sword die by the sword,” right? And while the Hêliand preserves that message, the author naturally has to play up what a badass swordsman Peter is, in full Germanic splendor:

Then plenteously wroth grew he

The swift swordsman, Simon Peter

It welled up with his heart so that not a word could he speak…

Bloated with anger, the bold-minded

Thane strode ahead, stood before his Liege,

Hard by his Lord; nor was his heart ever in doubt

Fearful within his breast, but he drew his bill

The sword at his side, and with the strength of his arm

He struck the first of the foe standing before him

So that Malchus was marked by the knife

On his right side, slashed by the sword’s edge

His hearing had been hewn: sore was the hurt ‘round his head

So that sword-gory, cheek and ear in mortal wound

Burst asunder, and blood did spring forth

Welling up from the wound… Those around stood away

Dreading the bite of the bill

But even after this lively poetry, Jesus still heals Malchus and rebukes Peter: “We must not destroy one whit with our deeds.”

The Beatitudes are a really interesting example of this tension between audience and message. Their substance is essentially unchanged from the gospels—poverty, gentleness, and peace are exalted—yet the framing of this message is of worthy warriors acquiring lands and treasure. Matthew’s “Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven” becomes:

Those war-men who ever will be right, and through this willingly suffer

The harm and hatred of richer men. To them is the Meadow

of God’s heaven then given, and the spirit’s good life

Forever, for all days, and the end never cometh

Of the winsome possessions.

The Hêliand author walks a fine line, preserving the substance of the gospels and in some cases even their metaphors, while making it seem desirable to glory-hungry warriors and plunderers. Honestly, I think the author nails it.

Image credit: Heiko Fischer. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

At your table, sure, the obvious way to be inspired by the Hêliand is to have the PCs come to a place where they find their religion portrayed in a way that’s very alien. It colors the way they roleplay with NPCs. The GM gets to gloat about their clever worldbuilding, and… that’s about it.

I think a cooler way to be inspired by the Hêliand at the table is to have the land the PCs are in be the one targeted by weird outside missionaries. These evangelists have come to spread a foreign faith. A lot of what they’re saying seems pretty compatible with local beliefs (whatever those are in your fictional setting). But here and there in the missionaries’ teaching are ideas that are truly foreign—maybe even virtues that the host culture doesn’t have words for (“humility” is an interesting and complex example in Old Saxon).

Some political leader or cultural figure tasks the party with figuring out what these missionaries really believe, what doctrine lies behind the altered version they made appealing to the locals. The characters can’t go asking probing questions lest the missionaries learn what they’re up to and switch to exclusively inoffensive pap adjusted for local tastes. No, the PCs have to passively collect texts like the Hêliand, read them, and argue about what they mean. My recommendation would be providing three texts, each about a page long.

Obviously, this is a huge amount of work for the GM and a lot of players would hate it and think it’s no fun at all. Before you do something ambitious and unusual like this, you have to ask yourself, “Will I still have enjoyed doing this prep even if the players bounce right off it and ask to go back to killing orcs?” You must be doing it because it’s fun for you and because you genuinely think your players might enjoy it. Otherwise you’re being unfair to yourself and to your players. But if both you and your players are a good fit for it, go to town!

A very, very important note: keep your interpretation of the “true” foreign religion flexible. If your players arrive at a conclusion that’s fairly well-supported by the evidence you’ve offered them, declare that interpretation correct. Absolutely no one wants to play a game of “guess what the GM is thinking”.

When parsing the text, the things the players would expect to see don’t matter. In the Hêliand it doesn’t matter that the disciples are warriors and great fighters. That’s only to be expected; it’s the pap the missionaries are feeding their audience to keep them listening. The stuff that’s weird, out of place, that doesn’t fit local ideas of what a religion should include—that’s the stuff that’s so important that the missionaries won’t change it to suit their audience. That’s what this religion is really about.

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Check out Shanty Hunters, my award-winning TTRPG about collecting magical sea shanties in the year 1880, then singing them at the table with your friends. The lyrics of the shanties come to life and cause problems for you and for the crew of the ship you sail aboard. It’s up to you to find clues in the song and put things right!

Sources:

Heliand: Text and Commentary by James E. Cathey (2002)

The Heliand: Translated from the Old Saxon by Mariana Scott (1966)