Shaking up a campaign setting that’s grown stale can be a tricky task. You can’t change too much or you’ll lose what your players love about the game, and they’ll lose the detailed setting knowledge they’ve gained. But if you don’t make things different enough, the exercise is pointless. For a great example of how to do it well, let’s look at (weirdly) the start of the Corinthian War!

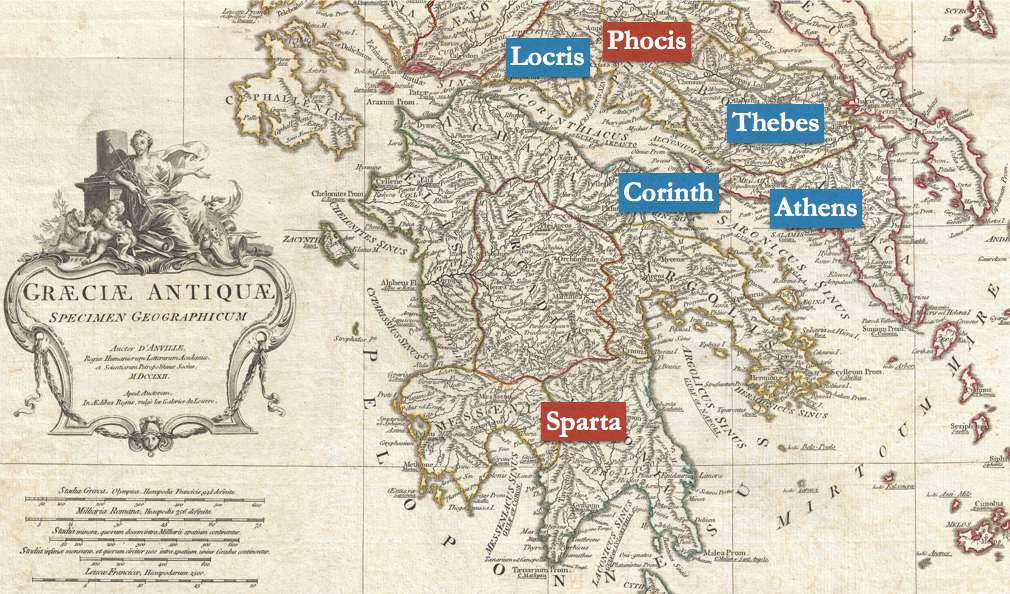

First, some ancient Greek background. In 404 B.C., the 30-year-long Peloponnesian War finally ended. The losing side was Athens, heading up a sizable coalition of the semi-willing and the unwilling (effectively an empire). The winning side was headed up by Sparta, but Thebes and Corinth were also major powers on this side, and towards the end of the war, they were bankrolled by the Persian Empire to the east. If Greece at the time were a campaign setting, the Peloponnesian War and the ideological conflict it represented (democracy vs. oligarchy) would have been the heart of the setting. But all wars must end eventually – especially after thirty frickin’ years. You can imagine the GM sitting at the table after a session wondering “What’s next? How can I possibly sustain what my players have enjoyed about this campaign without making it feel repetitive?”

The answer: keep the themes (war, politics, and ideology) and keep the factions (Athens, Sparta, Corinth, Thebes, and Persia), but change the ideological conflict and change who’s on what side.

Sometime around 400 B.C, Persia annexed the Greek city states in coastal modern Turkey. This was pretty common. Persia would annex them, the city-states in modern Greece would get mad about it, there’d be a few battles, and then everyone would come to an understanding. This time, the Spartans gather a big army to attack the Persians, who – don’t forget! – had until a few years prior, been funding the Spartan war effort. Sparta defeats the Persians’ army in the area, and Persia agrees to free the city-states they’d annexed. Note that this little military expedition – the precipitating incident for all the events that would shortly follow – still stuck to the themes of war, politics, and ideology that our GM built her campaign around. She’s still got her eye on the ball.

It’s not worth it for the Persians to retaliate militarily against Sparta, but Persia has other tricks up its sleeve. The Persians send an agent, Timokrates of Rhodes, to Greece with a big sack full of money. Timokrates bribes important politicians in Thebes and Corinth, saying “You should engineer the situation so that your city-state goes to war with Sparta.”

These bribes played right into the hands of a new ideological dispute in Greece: to what extent Sparta should be allowed to impose what it thought was right on the rest of Greece. Part of Spartan rhetoric during the Peloponnesian War had been that they were freeing Greece from Athenian tyranny. But now with Athens defeated, Sparta was acting almost as much like a tyrant as Athens had been. Sparta was increasingly willing to throw its political and military weight around, and a lot of Greeks weren’t thrilled to have Sparta meddling in what they saw as their business.

The bribed Theban politicians convince a nearby friendly region (Locris) to levy a tax they knew would anger another region (Phocis). As expected, Phocis retaliated by invading Locris. The Theban politicians were then able to say “Look! Phocis has attacked our friends in Locris! We should retaliate!” So Thebes defends its friends in Locris by attacking Phocis. The Phocians – suddenly on the losing side of a war they didn’t realize had been engineered from the start – appeal to Sparta for help. After all, Sparta’s supposed to be enforcing right and justice, right? Sparta is only too happy to get involved. While Thebes and Sparta had been on the same side of the Peloponnesian War, the Thebans had always been disrespectful of the Spartans. This, Sparta thought, would be an opportunity to give those big-headed Thebans a lesson in manners!

Meanwhile in Athens, Athenian politicians (who have not been bribed) see an opportunity to strike back at the Spartans, who led the forces that defeated and humiliated Athens only a few years before. The Athenians are delighted to help out their former enemies in Thebes if it means hurting Sparta.

The bribed politicians in Corinth have not been able to convince their city to help Thebes. But they are able to keep Corinth from helping Sparta. Corinth will come into the war on the Theban side next year, but for now, they’re sitting out this fight.

When the armies of the two sides clash, the Spartans are unexpectedly defeated. It’s a black eye for Greece’s supreme military power. Worse, Lysander – the greatest Spartan general in a generation – is killed! The Spartans actually sentence their own king to death for a variety of failures on this battlefield. The king flees Sparta, and dies in exile.

So begins the Corinthian War. This one will last eight years. It has a new ideological character: sovereignty, rather than democracy. It has a new set of alliances. But if classical Greek history were an RPG campaign, this would still be recognizably the same game as the Peloponnesian War. By using the same central themes the campaign has enjoyed so far (war, politics, and ideology), the GM has been able to shift the campaign in a new direction – but one still focused on those same themes. With a little luck, her players will be able to look forward to new challenges in a familiar setting.

–

(Tangent: The reason why the start of the Corinthian War ‘rhymes’ thematically with the Peloponnesian War probably has a lot to do with the historians who wrote about it. Both wars seem to have a lot to do with war, ideology, and politics because that’s what most historians writing at the time thought was important enough to warrant recording. The exception is my main man Herodotus (take that, Thucydides fanboys), but his Histories don’t cover the Peloponnesian War, and he died twenty years before its end.)