RPG adventures about social causes can be hard to pull off. How do you mesh the traditional adventure format with the mass action needed to address large-scale problems? One answer is by modeling your adventure on the efforts and obstacles of abolitionist Thomas Clarkson. Clarkson tried to go undercover to investigate the slave trade. He failed to stay incognito, but found allies in an unexpected place, and played an important role in outlawing British participation in the Atlantic slave trade.

(Note: this is a follow-on piece to last week’s blog post about slave traders along the West African Coast)

In June 1787, the London-based Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade had a problem. They needed data and stories about the trade to influence the public and Parliament. But the trade was insular. Captains and merchants didn’t talk about what happened aboard their ships. How was the Society to get the information it needed? A scholar named Thomas Clarkson volunteered to go undercover to find out.

Clarkson planned to visit the merchants’ halls and customs houses in Bristol and Liverpool, the two primary homeports of slave ships and the financial centers of the slave trade. He’d pose as a historian and review the documents there at his leisure. He also hoped to document an oral history of the trade by interviewing captains and officers. The merchants weren’t fooled. They didn’t let Clarkson see their records and they declined to be interviewed. They’d even cross the street to avoid coming near him in public.

So Clarkson turned to the common sailors who crewed these slave ships. ‘Respectable’ people like Clarkson didn’t talk to sailors, but he didn’t have much choice. He found them in rundown dockside taverns, full of “music, dancing, rioting, drunkenness, and profane swearing”. Many were mutilated and diseased, left unable to work by the harsh conditions and cruel discipline common to slave ships. He learned of captains who murdered sailors for offenses that would have earned them a flogging on a regular merchant. Sailors who’d crewed slave ships were bitter, abused, and happy to tell Clarkson all they knew.

Clarkson’s work was not without its hazards. He had to stay at inns in Bristol and Liverpool, and the dining areas were public. Slave merchants and captains stopped by during dinner to debate, insult, and threaten him. He got anonymous death threats in the mail. Somebody even tried to make good on the threat: one stormy afternoon in Liverpool, a gang of men tried to drown him. The abolitionist learned not to go anywhere without an escort.

Meanwhile, sailors streamed into Clarkson’s lodgings to tell their stories. They told him of how Africans were kidnapped from their homes, chained together, stowed belowdecks in murderous conditions, beaten if they wouldn’t eat, whipped if they wouldn’t ‘dance’ for exercise, and taught proper obedience to the white man with thumbscrews and the cat-o’-nine-tails. And the sailors told Clarkson of their own mistreatment at the hands of cruel captains. Despite having no background in the law, Clarkson filed nine suits in court on behalf of mangled or murdered sailors. In each case, he won a monetary settlement for the sailor or his family.

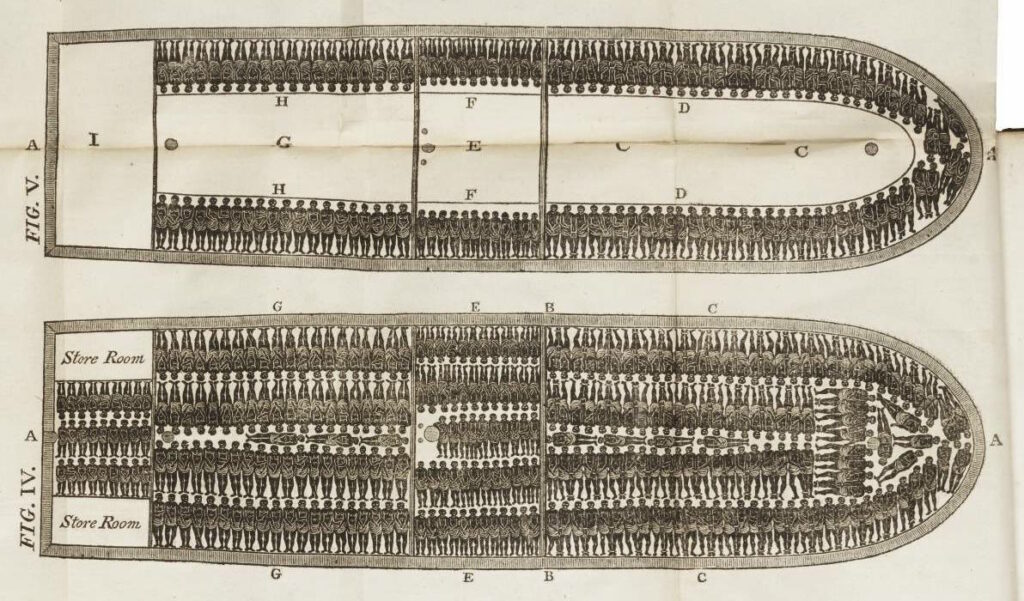

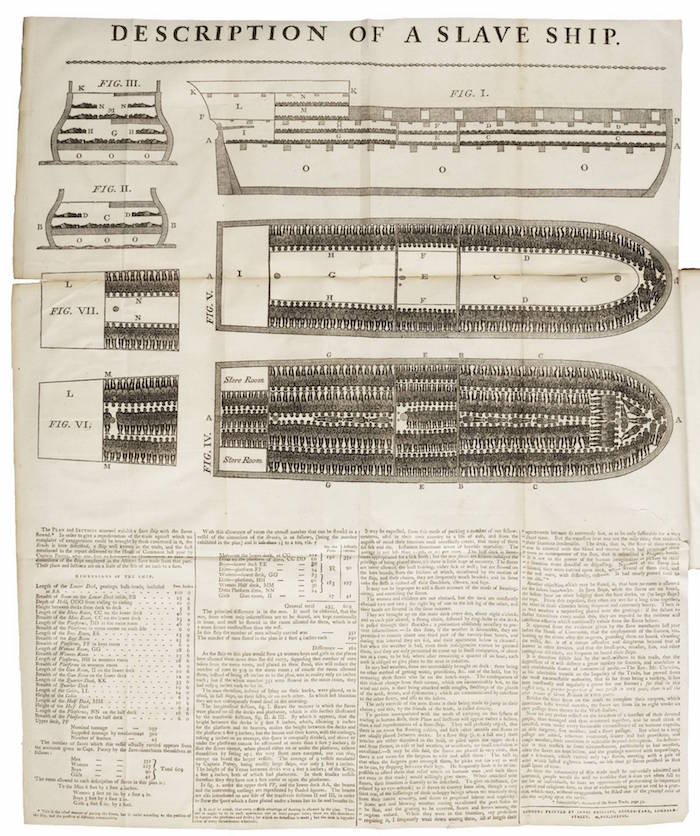

Clarkson’s work informed his writings and abolitionist arguments. You’ve probably seen the drawing of the slave ship Brooks (detail, above). It was refined and reproduced in broadsheets by abolition committees in both America and Britain. The image shocked Europe. Yet upsetting as it was, the Brooks illustration doesn’t leave room for the stanchions and latrine tubs that took up further space – and only shows two-thirds as many enslaved people as the Brooks actually carried. The image that horrified Europe was a best-case scenario.

But the image was only part of the story. Most of the broadsheets (example, below) paired the illustration with descriptive text detailing conditions aboard slave ships. Almost all this information came from Clarkson’s research. Clarksondidn’t shock Europe all on his own, but it couldn’t have happened without him.

Clarkson’s sailors made it before the British Parliament, though their time was not easy there. Here I have to quote directly from Marcus Rediker’s The Slave Ship: A Human History, my main source for this piece.

“When seaman Isaac Parker was introduced during the House of Commons hearings in March 1790, an observer wrote that the ‘whole Committee was in a laugh.’ The pro-slavery members then taunted William Wilberforce, abolition’s leader in Parliament, ‘will you bring your ship-keepers, ship-sweepers, and deck cleaners in competition with our admirals and men of honor? It is now high time to close your evidence, indeed!’ Undaunted and speaking in short, simple sentences, Parker described among other things, the flogging, torture, and death by Captain Thomas Marshall of the enslaved child who would not eat aboard the Black Joke in 1764. Like dozens of other seamen, Parker spoke truth to power; his detailed testimony damned the trade in ways that abstract moral denunciation could never have done.”

The information the Society presented proved effective. Despite a pressure campaign by the wealthy pro-slavery faction, in 1792, the lower house of British Parliament passed a bill abolishing slavery. The upper house, more financially entangled with the slavers’ interests, quashed it, and the start of a war with France in 1793 tabled the abolition debate. Peace broke out in 1802, and in 1807, Britain criminalized the slave trade. It had been only twenty years since Clarkson began his research.

The difficulties Clarkson and the London committee faced make a great template for an adventure around almost any progressive or human rights issue: any cause that is both setting-appropriate and appealing to your players. Any PCs with a reputation for tough-minded investigation and a moral backbone might be contacted by a committee founded to address your chosen issue.

To adapt Clarkson’s investigation to your table, you must first determine which NPCs in your setting will play which roles in the drama. Who are the merchants, the respectable authorities who enrich or empower themselves through the suffering of distant wretches? Who are the captains, the well-compensated middlemen who enforce the will of the merchants on the ground? And who are the sailors, the poor and downtrodden who actually do the work of evil, often without much choice?

For example, if the issue is forced migration, the merchants are the tycoons and territorial officials who will profit from new lands being opened up. The captains are the military officers who get kickbacks for forcing people off their land. And the sailors are the common soldiers who must follow orders, and who may shoot the dispossessed if they resist.

In the real world, 20 years is remarkably fast for criminalizing a vast and profitable industry, but at your table, you’ll probably want to go faster. Everyone likes seeing their in-character actions bear fruit. If your setting has a government with strong executive power, that will help speed things up. Instead of being ridiculed by MPs in Parliament, they may be ridiculed by courtiers while addressing the Empress. But if they can convince the Empress to rule in their favor, they may be able to achieve their goals on the spot.

Finally, there’s an ethical concern with regards to the sailors. Clarkson’s good relationship with sailors made his research possible. But the sailors also carried out many of the worst excesses of the slave trade. True, the most heinous crimes – like whipping a child to death aboard the Black Joke – were typically carried out by the captain. But most of the day-to-day brutality was meted out to the ship’s enslaved ‘cargo’ by the sailors. They were victims of terrible mistreatment by the captains and merchants, but were themselves perpetrators of horrific violence upon the very people the abolitionists were trying to help. Do your PCs want to maintain good relationships with these people? Do they want to go to court to right wrongs against them? Or will they see the sailors’ sufferings as just punishment for their own barbarity?