The Tsembaga were a tight-knit cluster of clans that lived on the fringes of highland New Guinea. Around 1930, they almost went to war with their neighbors, the Dimbagai-Yimyagai. The reasons why the war never materialized are complicated, and they make a great template for a diplomatic or social adventure rooted firmly at the level of a local community, not a great nation-state.

This post relies on fieldwork conducted by the late Roy Rappaport in 1962-1963. Things change fast in Papua New Guinea. The Tsembaga formed as a unit only 50 years before Rappaport began his fieldwork, and it’s been almost 60 years since. Those decades have seen enormous changes, including the formation of Papua New Guinea as its own nation. Since I have no way to know what things look like on the ground in (former?) Tsembaga territory today, I use the past tense in this post.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

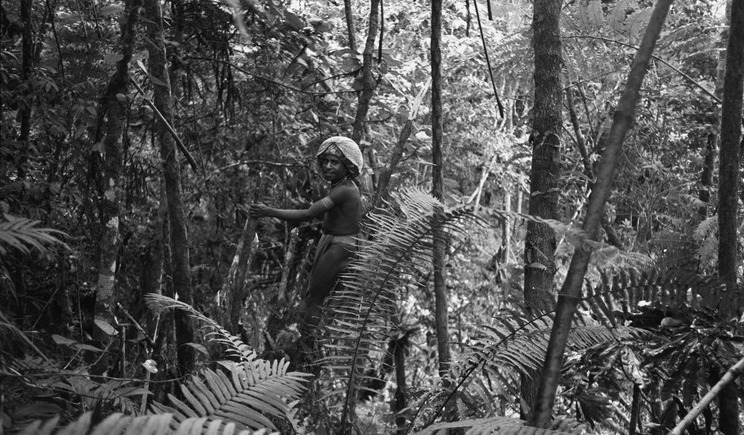

Credit: Roy Rappaport Papers, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego

The Tsembaga were a group of about 200 people, divided into five clans, occupying three square miles of rainforest on the edge of the New Guinea highlands. They spoke a dialect of the Maring language. About twenty other clan clusters spoke some dialect of Maring, but not all the dialects were mutually intelligible. I say this to drive home the staggering diversity of the people in the area – Maring-speakers collectively occupied not even a hundred square miles (a square ten miles on a side), yet they couldn’t all talk to one another. The Tsembaga were one small part of the Maring, and the Maring were one small part of the multitude of language groups just in their local area. Back in 2018, I wrote about a rebellion in Bagasin, New Guinea, only 50-odd miles away. Yet the Tsembaga and the folks in Bagasin were completely different, and had little (if any) contact. We’re talking about heterogeneity on a scale almost inconceivable to us.

The best way to think about the Tsembaga might be as five interrelated extended families sharing a single church. Though the five Tsembaga clans maintained separate sub-territories (one square mile apiece or smaller), they were careful to coordinate the timing of their rituals so all the clans performed them at the same time. Though there were only 200 Tsembaga, this wasn’t a Hills-Have-Eyes situation. Half of Tsembaga wives were non-Tsembaga by birth, and the Tsembaga didn’t marry within the clan. They maintained gardens in the forest, cleared with traded Australian steel axeheads. They kept pigs and hunted marsupials with stone-tipped arrows. They devoted considerable time and effort to the proper performance of the Tsembaga religion. And they mostly got along with each other – but not with their neighbors. Shared enemies brought the five Tsembaga clans together in the first place, and had kept them together in the decades since.

Finally, important for our needs today, the Tsembaga had no chiefs, headmen, or political officials of any kind. If someone wanted something done, they had to convince others to do it. Some people (‘big men’) had a better track record of success, but that was the extent of their authority: they were people who’d been persuasive in the past. The Tsembaga sometimes held meetings to discuss issues, but there was no vote held. Men simply broke into small groups to talk, giving the opportunity for opinions to be shared. Direct statements (“We must do this! Who’s with me?”) were avoided, as that sort of directness might trigger a confrontation. The Tsembaga had quite enough violence to deal with coming from their neighbors without risking it amongst themselves. If someone judged a consensus had formed, he’d just start doing the thing (clearing a dance ground, gathering materials for a ritual, or damming a stream), and hoped others would join in. Misjudgments were common, even by ‘big men’.

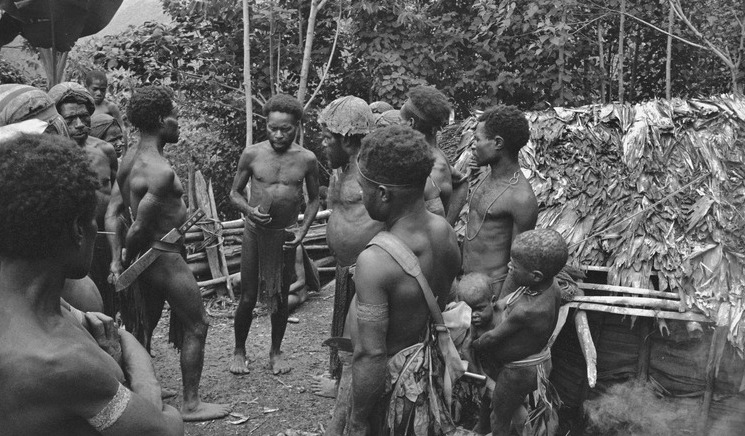

Credit: Roy Rappaport Papers, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego

A system like this – small territory, enemies on all sides, no leaders, and everyone related to everyone else – is perfect for complicated, messy political and diplomatic scenarios. And we have a perfect one from around 1930!

A path the Tsembaga used to reach their hunting grounds passed along the edge of the territory of an enemy clan cluster, the Dimbagai-Yimyagai, and went right past the garden plot of a man named Paŋwai. Tsembaga hunters were in the habit of swinging by Paŋwai’s garden on the way home from hunting, grabbing some sugar cane, and drinking the sweet cane juice. Paŋwai saw this as theft. One time, Paŋwai saw a man named Kati drinking his sugar cane, grabbed a bow, and shot Kati. The wound wasn’t serious; Paŋwai got Kati in the butt, and the arrow wasn’t barbed. Kati, however, was livid.

But Paŋwai and Kati weren’t who they seemed to be at first glance. Paŋwai was living with the Dimbagai-Yimyagai, but he was actually Tsembaga by birth. In fact, at the time there were eight Tsembaga farming (with permission) on Dimbagai-Yimbagai land. And Kati was living with the Tsembaga, but was actually from a ‘far-off’ clan that didn’t even speak Maring, and was crashing with his sister, who’d married a Tsembaga man. Since he wasn’t blood kin, the Tsembaga weren’t obliged to avenge him. No Tsembaga were harmed in the altercation, and no Dimbagai-Yimyagai were even involved!

Nonetheless, the Tsembaga were pissed. Kati was a guest, and they felt responsible for him. And while Kati was in the wrong, he wasn’t wrong enough to justify being shot with an arrow – which in this case was harmless, but could certainly have killed him. The Tsembaga consensus was that if Kati had been stealing Paŋwai’s taro roots, Paŋwai would have been within his rights to shoot him. But shooting a man over stealing candy went too far. Even though Paŋwai was Tsembaga by birth, he was living as a Dimbagai-Yimbagai, so the whole Dimbagai-Yimbagai clan cluster was on the hook for Paŋwai’s wrongdoing.

Credit: Roy Rappaport Papers, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego

Before this dispute went anywhere, there were opportunities for diplomacy. There was enough intermarriage between the Tsembaga and the Dimbagai-Yimbagai that in a fight, close relatives might have to fight each other. No one wanted that! And the Tsembaga had no chiefs, so a consensus could have developed that this fight wasn’t worth it. Alas, the Tsembaga formed no such consensus. Similarly, shared relatives (probably in-laws of in-laws, but it still counts) of Paŋwai and Kati could have pressured them to knock it off, but if they tried, it didn’t work. A final chance for diplomacy rested with the outside clans each side was allied with. If one side’s allies in another clan cluster decided the fight wasn’t worth interrupting their gardening and risking their lives over, they might have declined to show up. No-shows (or the threat of a now-show) often settled these disputes before they escalated. In this case, both side’s allies dutifully agreed to answer the call, so no luck there.

Once it became clear the dispute between the Tsembaga and the Dimbagai-Yimbagai was going to come to blows, the next step was to gather materials for ‘fight bags’. A fight bag contained certain plants and something from an enemy: his hair, a scrap of his clothing, or dirt scraped from his skin. Possessing a fight bag was believed to make warriors more confident and to increase the likelihood they’d kill that particular enemy. Obtaining material for a fight bag was a social challenge unto itself. Combatants had to convince neutral parties, usually in-laws of folks on the other side, to pay a visit and purloin something for the fight bag. Supposedly, if a man was suspected of being a witch, his own brothers might steal some fight bag materials and pass them along to the enemy by way of a neutral party, just to rid themselves of his wickedness.

The next fight was the ‘small fight’ or ‘nothing fight’. A nothing fight was a ritualized engagement not unlike the one I wrote about in my 2019 post Resolving Disputes the Tiwi Way. Both sides met at an agreed-upon place and time, set up big shields as cover, and shot at one another from behind the shields. Nothing fights were usually pretty safe; it was rare for someone to die. Mostly, it was an opportunity for each side to gauge the strength of their opponents.

Credit: Roy Rappaport Papers, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego

Mercifully, the 1930 dispute seems to have gone no further than a nothing fight. It’s far from certain, but it seems like one of the two sides made a significantly better showing at the nothing fight, and the ‘losers’ retreated from the field. Unwilling to grapple with a superior enemy over a trivial concern, the losing side agreed to drop the matter. Unfortunately for us, the fight was 30 years old when Rappaport investigated it, and different sources reported contradictory details, even over which side lost!

But often, disputes like this didn’t end at the nothing fight. They escalated to open warfare. There was still a chance for peace, of course. The Tsembaga’s consensus-based approach meant that it took several days to hash out whether the group would go to war. During that time, the same factors that could produce peace before the nothing fight could still be brought to bear. Peace was especially likely if no one died or was badly injured in the nothing fight, or if previous bouts of warfare had left both sides with a roughly balanced tally of casualties – in other words, if there was nothing to avenge.

Warfare was chaotic. Maring-speaking settlements were rarely more than a mile or two apart, so there was no front line and barely a concept of raiding parties. It was mostly just people trying to kill each other in their own backyards, sometimes in a ritual manner, sometimes not. There were frequent truces during which both sides could agree they were done fighting. A sudden victory meant the winner overran the loser’s small territory, killing every man, woman, and child he found. Surviving losers fled to go live with their in-laws and relatives in other clan clusters. The Tsembaga themselves were driven from their territory from 1953-1957.

Credit: Roy Rappaport Papers, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego

So what we’ve got here is an amazing template for a diplomatic adventure. I say template because, as always, you’ll want to file off the serial numbers to fit it into your fictional campaign setting. This works in any setting with hill people: those who are insular, clannish, and prone to fighting with their neighbors. The PCs can show up for some unrelated reason (searching for a MacGuffin, hiding from the law, whatever), and discover this brewing fight over the short-sightedness of two NPCs based on Paŋwai and Kati. See if you can get the PCs to intervene!

Lean on the fact that the lines of alliance are muddy. If either side will disavow their dude (who isn’t part of the clan anyway), the party can turn this whole mess from an escalating war between two clan clusters into a petty dispute between two individuals. As there is no chief to intervene, the PCs can seek out folks who are related (via marriage) to both your Paŋwai- and Kati-analogues and get them to lean on these guys to knock it off. If Kati will admit he overreacted and/or Paŋwai will admit he’s not blameless, this whole thing goes away. The party can also try to get some big men to sway the consensus of their groups. Ditto with talking to both sides’ allies to get them to declare they won’t show up. If Paŋwai or Kati are no longer confident their side will support them, they’re more likely to back down.

If things still develop towards a nothing fight, the PCs may want to pick a side to back. If one side is clearly dominant, it can cow the other side into backing down. To support a side, you’ll want to convince neutral parties to get fight bag material for your favored side. You might even sow suspicion of witchcraft on the disfavored side so folks over there volunteer fight bag material to your favored side. If the fighters on your favored side all show up carrying fight bags and put forth a strong showing in whatever your version of the nothing fight looks like, maybe the disfavored side will swallow their pride and back down.

Source: Pigs for the Ancestors: Ritual in the Ecology of a New Guinea People by Roy A. Rappaport (1968)