Societies, especially cities, have handled the enforcement of laws a lot of different ways in different places and times; the ubiquity of police in the 21st century can make it hard to imagine what other systems might even look like. One particularly gameable institution was the ‘night watch’. This system was found in a few European cities in the high Middle Ages, and by the end of the Renaissance it had spread to almost all cities in Europe and North America. Let’s look at what made the night watch weird and different – and the ways that putting one in your fictional campaign setting can lead to memorable adventures!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Robert Nichols. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Robert, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

To talk about the night watch, we first have to talk about night itself. In a pre-industrial world, artificial light was expensive. Candles of tallow and beeswax are animal products, so can be produced only in limited amounts. Firewood, peat, and dried dung are labor-intensive to gather and prepare. So too is olive oil or flaxseed oil for lamps. Before gas and kerosene, you could light the night if you really wanted – but it would cost you. Consequently, nights stayed dark. Most Europeans were home by twilight, barred their doors, and stayed indoors. In the Middle Ages, many cities imposed curfews: only a select few were permitted out after dark. This cut down both on burglaries and people breaking their necks falling into open cellars.

But having an entire city asleep posed its own problems. The biggest was fire! Medieval European cities were tinderboxes. Entire city blocks burned down every year. And if no one was awake at midnight when someone’s improperly-banked coals set their house on fire, the blaze might spread to multiple houses before anyone even noticed. Plus, you had the problem of crime: if no one else was about after dark, that gave thieves full run of the night. The solution to these problems (and honestly more the former than the latter) was the night watch.

Many night watches began as citizen’s brigades, with each able-bodied male resident assigned to patrol the streets so many nights a year. As early as 1150, the guilds of Paris were on the hook for providing the city’s watchmen. Sentinels sat in the tallest church steeple in town to watch for fires. (Amsterdam was big enough that the watch manned four separate steeples!) Other watchmen patrolled the streets alone or in pairs watching for fires and thieves. Your beat might cover the whole city or just your own neighborhood. If you saw a fire, you set up a cry so sleepers could awaken and help put it out. If you saw a burglar, you tried to grab him so he could appear before a magistrate in the morning. For worse crimes, you also started the ‘hue and cry’ to summon your sleeping neighbors to help. This watch system, while practical, was unpopular. No one much liked being a watchman. If you could afford it, you hired a substitute to take your place.

As night watches spread to more cities, they also tended to do away with the onerous requirement for all townsmen to pitch in. Watches ‘professionalized’, but poorly. The pay was garbage, the nights were cold, and there was the very real danger of falling into a hole on moonless nights, even with a lantern. Thus, watchmen tended to be folks who had difficulty finding other employment: the aged, the very young, the weak, the poor. Many held down jobs during the daytime too, which left them sleepy and slow at night. Improbably, one of the best period portrayals of night watchmen might be Dogberry from Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing.

Dogberry:

If you meet a thief, you may suspect him, by virtue

of your office, to be no true man; and, for such

kind of men, the less you meddle or make with them,

why the more is for your honesty

Other watchman:

If we know him to be a thief, shall we not lay

hands on him?

Dogberry:

Truly, by your office, you may; but I think they

that touch pitch will be defiled: the most peaceable

way for you, if you do take a thief, is to let him

show himself what he is and steal out of your company.

Here’s Michael Keaton as Dogberry in the 1993 film version.

Adding to the poor reputation of the lowly night watchman was the (to me) bizarre practice of announcing the time. As they patrolled, watchmen in many cities shouted sing-song rhymes giving the hour. These ditties might also encourage Christian virtues and express a fond hope that the listener was sleeping well. So no sooner might you nod off but somebody’s fourteen-year-old servant working his second job comes walking past your window waking you up by shouting about how he hopes you’re getting a good night’s sleep. In some cities, watchmen were also expected to try the doors of houses they passed to make sure they were locked or barred. All this supposedly deterred burglary by making the city’s residents light sleepers, but I can’t think of many less pleasant ways to do it. As an example, from northern England:

Ho, watchman, ho!

Twelve is the clock

God keep our town

From fire and brand

And hostile hand

Twelve is the clock!

Also from England:

Men and children, maids and wives

’Tis not too late to mend your lives

Lock your doors, lie warm in bed

Much is lost in a maidenhead

Now that I’ve told you a bunch of generalities, I ask you to forget all of it! Of course night watches were different everywhere; no two cities are alike. 1400s Venice had a professional watch for the town and a separate volunteer watch for the shipyards drawn from shipbuilders. Saint-Malo in France in the early 1600s just released a pack of hungry mastiffs inside the city walls every night. They weren’t any good at stopping fires, but they straight-up ate thieves. Mid-1500s York, Yorkshire had a force of six men per ward. Mid-1600s New York, New York had eight. Berlin didn’t have a night watch until the early 1600s. Dublin didn’t have one until 1677. Tiny Maldon, Essex finally established a three-man watch in the 1700s only after a spate of burglaries. While most cities armed their watchmen with a lantern on a stick, Norwegian and Danish watchmen carried morning-stars, Stockholmers carried man-traps, and Amsterdammers carried a rattle for alarms and a pike. American colonials often carried guns for fear of Indians. Parisian watchmen rode on horseback.

Image credit: MichaelMaggs. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

In your fictional campaign setting, it can be a lot of fun to put in place an institution based on the night watch rather than defaulting to ‘21st-century police with setting-appropriate equipment’. Having the constable be a grumpy tradesman doing his annual service or an incompetent, underpaid ‘professional’ – and having either of them just as concerned with fire as with crime – introduces new opportunities for adventure your players might not have seen before.

In 1724, a gang of drunken London watchmen arrested 26 women in one night. London did not have a curfew, so these women were arrested merely because the drunken watchmen thought they seemed suspicious. The constables locked the women in a roundhouse with sealed windows and doors. At other times, London had a night magistrate for such purposes, but evidently not that night – the detainees would have to be seen in the morning. By morning, all 26 had suffocated to death. At your table, if you want to complicate something the PCs are doing in a city at night, you might have them arrested by incompetent and suspicious watchmen. After some Dogberry-esque antics, if the party can’t get away from the watch, it’s in the roundhouse with ‘em (or sealed airlock or whatever). That’s when things get serious. The PCs have a firm time limit to get out of the roundhouse before they all suffocate.

Night watchmen were not popular. In 1635, in Næstved, Denmark, two watchmen ran afoul of a group of journeymen shoemakers. The shoemakers drew knives and chased the watchmen, shouting “Kill them! Kill them!” The watchmen ran all the way to the mayor’s house and dragged him out of bed to save them. At your table, having your PCs stumble into the scene at this moment might be a great way to complicate their current fictional adventure. Some screaming, knife-wielding tradesmen; a pair of cowering watchmen; a bleary-eyed mayor in her bedclothes; and a gang of adventurers who unintentionally arrived in this mess and have to find a way out without angering the trades, the watch, or the political establishment.

Finally, night watchmen had a natural tension between the crime-deterrent and fire-warning parts of their jobs. Your PCs and your villains might take advantage of that. A fire in the right place at the right time can occupy the night watch and create an opening for further mischief. The PCs might be asked to catch a gang of mafiosos using just such a technique. But once they’ve done so, they face a dilemma: do they use the new technique themselves?

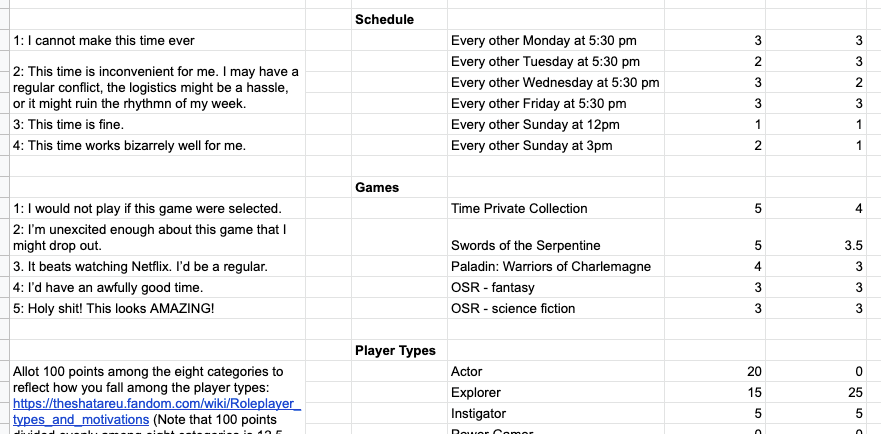

I’d like to talk about a gaming habit I’ve used for a decade. It works really well and I’m astonished it’s not in wider use: voting sheets for starting campaigns.

I’m starting a new campaign with my in-person gaming group. (I know many of my dear friends with whom I game online read this blog – I’m sorry! I’ll run something for you again soon, I promise!) And I did what I always do: I drafted a document talking about five-ish campaigns I’d be super excited to run and I asked my players to rate each one. The pdf document is here and the Google Sheets where everyone votes is here. (My players gave permission for me to show you their real votes.)

The document briefly explains my intentions with the campaign (episodic, 7-ish sessions). Then it describes each campaign in one or two paragraphs. Some ‘campaigns’ are really pitches for RPGs (Swords of the Serpentine, Paladin: Warriors of Charlemagne), while others are campaign premises in the more traditional sense (“So you’d be laid-off former time-traveling agents of a future history museum…”). All have a relevant image or two as illustration.

Then the players went to the Google Sheets to rate each game on a scale of 1 (“I would not play if this game were selected”) to 5 (“Holy shit! This looks AMAZING!”). In this case, Time Private Collection (a FATE campaign) was the clear winner, so that’s what we’re going to play. Players similarly rated different evenings for how convenient they were as regular game nights. They also – and this was a first for me – ranked their play style (Actor, Explorer, etc.) so I can better tailor the campaign to what they enjoy.

I’ve been using this system for 10 years. It works so well! I don’t know about you, but my shelves are groaning under the weight of awesome RPGs I’ve never gotten to play, and my notes are overflowing with campaign ideas. I have way more that I am very excited about than I will ever get to actually run. So I let my players choose! It greatly increases player-buy in because you know everyone there is excited about this specific campaign – because they told you! And because you only put things you’re super excited about on the voting sheet in the first place, you don’t have to worry about getting ‘stuck’ running something that you, as a GM, aren’t thrilled about. It’s a total win/win.

Some people on the Internet have told me their players would refuse to vote. “They insist they’ll play whatever I run.” Well I say screw that! I don’t want merely to occupy my players’ time. I want to excite them! And the best way I’ve found to make sure they’re excited is to force them to tell me what ideas do and don’t excite them.

And the results can be surprising! I like to throw one or two obscure or offbeat RPGs on my voting sheets. Usually they get ranked low. That’s no surprise; most unusual RPGs are little-known precisely because they’re not everyone’s cup of tea. But every now and again I’ll float a weird game and it turns out everyone – independently – is exactly the kind of weirdo that this RPG appeals to. And I’d never have known if I hadn’t put it on the sheet.

So seriously. If there are multiple games or multiple campaign ideas that make you say “Oh man, I so hope I get to run this someday!”, you should be using voting sheets.

Sources:

At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past by A. Roger Ekirch (2005)

The Long Run Demand for Lighting: Elasticities and Rebound Effects in Different Phases of Economic Development by Roger Fouquet & Peter J G Pearson (2012)