The east entrance to the Iron Age hillfort at Maiden Castle, Dorset, England, makes a really great battlemap for RPG combats. Lucky for us, it also has some really interesting history and archaeology behind it! As a battlemap, it’s got strongpoints a single PC can hold, branching paths, and restrictions on movement that are interesting hindrances, rather than hard stops. It led to the best combat of my 13th Age campaign, so I figured I’d better write it up!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Humans have been building defensive structures on the two hills of Maiden Castle since the Stone Age. In the early Iron Age, circa 800 B.C., folks updated the defenses around one of the hills into a proper hillfort, then extended the fort to encompass the other hill too around 550 B.C. The phase of the site we’re interested in came around 200 B.C., when the fort’s east entrance reached its zenith of height and complexity. Not long after the Romans invaded in 43 A.D., the fort fell out of use.

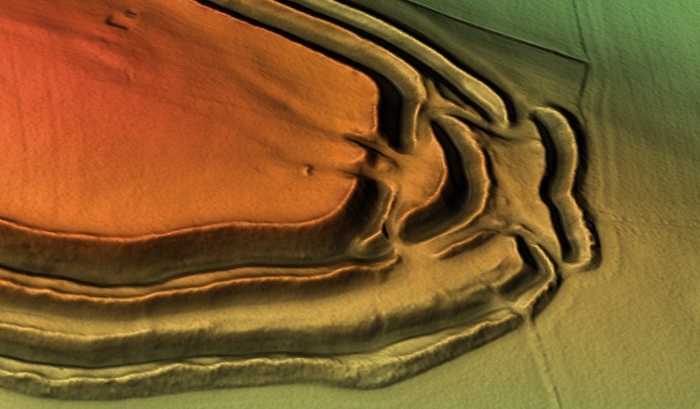

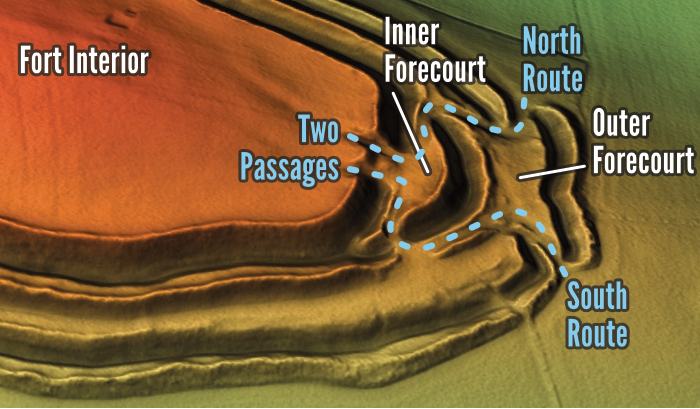

The earthen ramparts built around 200 B.C. were of a design that seem peculiar today. They’re not steep. They’re tall – more than four yards high at the time of construction. They have ditches in front of them, making them taller still for any attackers approaching from the front. But the earthen dikes had a slope of maybe 45 degrees at construction. That’s plenty steeper than you can easily run up, but it’s no wall. And Maiden Castle’s builders knew about walls. These new earthen ramparts replaced old ones that included retaining walls facing outwards. Both the new and old ramparts were probably topped with wooden pallisades and fighting positions. This all means the sloped sides of the newer ramparts were a deliberate choice. They let the fort’s inhabitants build the ramparts taller, and they formed part of a complicated network of defensive structures.

Starting from inside the fort, if you wanted to leave, you had two gates to choose from. Maybe in peace time, one was for ingress and one for egress? Both were timber and each opened onto a passage through the tallest, innermost rampart. The passages had sheer sides, held in place with stone and timber. And they were longer than the rampart was thick – the rampart actually curved in to make the passages even longer.

Once through either passage, you stood in the inner forecourt. The main rampart you just passed through towered above you. Beyond the inner forecourt, a double rampart with a deep ditch between them faced out towards hypothetical besiegers. There are two exits from the inner forecourt: one to the north and one to the south. Both are narrow and flanked by ramparts and ditches. Either route takes you to the outer forecourt, which similarly has two ways out onto the plain beyond: one to the north and one to the south. The outer forecourt is also guarded by a double rampart with a ditch between, forcing you into one of these narrow choke points.

Approaching Maiden Castle from the plain, then, is the same in reverse. You’re faced with a hill upon which have been built a series of steep (albeit climbable) earthen ramparts. There are two ways up the hill from the east: one northern, one southern. They take you to the outer forecourt, where you must choose one of two routes to to the inner forecourt, then one of two passages up to a timber gate and the fort interior beyond.

It’s a very interesting design, and we’ll talk about using it as a battlemap, but first a bit more history.

Why go to all this trouble heaping up earth and not even make your ramparts into walls? The answer has to do with how you attacked a hillfort. Caesar, in his Commentaries on the Gallic War lays it out for us. The defender put slingers atop the ramparts: men with slings who’d rain stones upon the enemy to keep anybody from getting too close. An attacker had to use their own slingers (or javelins or whatever) to drive the defenders off the rampart. Then a team of attackers rushed forwards, huddling under their shields, for the defenders would not be driven off the ramparts long and probably never completely. This team dragged brush up to a timber gate, then lit it aflame. The fire would eventually collapse the gate. Then the attackers could rush in and hope to overwhelm the defenders.

Maiden Castle’s elaborate, counterintuitive defenses were built to try to counter that tactic. Early in the battle, defending slingers could stand atop the outer ramparts to engage the attackers farther from the fort. This kept the attackers away from the precious gates. If the attackers managed to drive the defenders off the outer ramparts, those ramparts still made it hard to get close to the fort. Slingstones lose momentum when fired upwards towards the top of a hill. Attackers had to be close to the inner ramparts if they wanted to drive the defenders off. The outer ramparts occupied the space the attackers would need to stand in, and if you stood atop them, you presented a delightful target for the defenders. Don’t forget that in all this, the defenders were probably crouching behind wooden fighting positions to reload their slings. Thanks to their elevation, they could chuck their stones farther than their attackers, and gravity gave their missiles some extra power.

The nested ramparts created a system of narrow paths, forecourts, and chokepoints that lengthened the distance the brush-draggers had to advance under fire. Ditto the lengthened passageways before the gates, which gave the defenders one last constrained area where they could rain death on the attackers from above. Naturally, the attackers had to run uphill the whole way, which tuckered them out. This all helps explain why Maiden Hill and late Iron Age hillforts like it didn’t bother with giant walls. They could build sloping earthen ramparts higher, and even if somebody chose to run up the rampart instead of up the easier grade of the path, it didn’t make much difference to the defenders. The attackers still had to cover a lot of ground under heavy fire that they’d have trouble returning.

When using Maiden Castle’s east entrance as a battlemap at your table, I recommend not using it in a siege. That honestly doesn’t sound like a huge amount of fun. Rather, use a hillfort that’s fallen into ruin. You can have any reason why the people or thing the party’s after is either in the ruins or – even better – also entering the ruins. That way, the PCs and their enemies are both passing through this kind-of-maze going in the same direction. They have lots of places where they can stand and fight, and lots of places where they can bypass one another.

In 13th Age, I stuffed the ruined hillfort with ghosts and had some zombies the PCs needed to kill be lumbering towards the hillfort. If the zombies got inside the final rampart, they’d be safe; the ghosts would be more than a match for any PC who followed the zombies inside the fort. Instead, the zombies split into multiple groups, each with some escorts who could hang behind and slow down the PCs. With two routes into Maiden Castle (and two places where the routes crossed) the zombies had a lot of options to choose from, and so did the PCs when they pursued.

Plus, neither side is actually restricted to the paths! The fact that the ramparts are sloped is a strength of this battlemap. Make it taxing and expensive to go off-path, but make it a viable option. That way, when someone (either PC or enemy) posts up in a choke point, the question of whether to go around them is an interesting one, rather than a no-brainer. Personally, I made the terrain between the paths cost extra move to get through, and also filled it with ghost-infused thorn bushes that dealt a little damage.

So you’ve got choke points where the paths enter the forecourts, difficult (but not impassable) terrain, and branching paths. Running a combat on this terrain served for me as an object lesson in how to make terrain interesting. My players ended the session by telling me, “More combats like that one, please! We had to make some really interesting decisions to win.”

In October, I played in a one-shot of Shadowdark, a new OSR dungeon-crawler that raised a gazillion bucks on Kickstarter. It impressed the hell out of me. There were two facets of the rules that felt like tiny changes but had an enormous impact on the play experience in the coolest way.

First, torches in Shadowdark last for one hour of real, at-the-table time. When someone lights a torch, they start a countdown timer on their phone. Doesn’t matter how fast or slow you delve these dark, cramped dungeons, in a four-hour game you will burn four torches. This really served to keep play focused. Even with a table full of folks excited about the game, tangents and digressions will happen. I had such a table, and we caught ourselves twice digressing and said “Let’s put a pin in that. We don’t want to lose these torches.” We only started the game with two torches, and what few we were able to scrounge during our crawl were precious. For creating a focused, no-tangents game atmosphere, it was incredibly effective.

Second, Shadowdark is played entirely in initiative order. Initiative is just going around the table in seating order, but you keep playing with each person taking a single turn in order even when there’s no combat happening. This entirely eliminated analysis paralysis. High-lethality OSR play can sometimes slow to a crawl as players discuss the best way to approach a mysterious dungeon room. The consequences for messing it up are high, so nobody wants to be the one to see what happens if you pull the lever or gouge out the statue’s eyes. But when everything is played in initiative order, when the GM turns to you and says “OK, what do you do?” you have to give an answer. Even if that answer is simply “I pass” or “I propose this suggestion to the group,” you had to do something. And you know full well that only a few turns of people not doing things will go by before someone will unilaterally attempt something.

We were clearing dungeons at twice – even three times – the rate that I’ve seen dungeons cleared in comparable games, like Mork Borg or Mothership. No digressions, just things happening. We had an absolute blast. It was one of those games where your cheeks hurt at the end because you’ve been smiling so much.

If anything, these two mechanics might have been too effective. We played for about three hours of actual gameplay (not counting explaining the rules, bathroom breaks, etc.) and that was about as much as I could do. Any more might be exhausting – players are on, nonstop.

–

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audience is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Sing and fight magical folk ballads in 1813 England and Scotland! This free early-access edition has everything you need to play a Ballad Hunters one-shot about the traditional song Barbara Allen.

The game has:

- Investigative adventures centered around the lyrics of traditional British ballads

- Simple, story-driven rules inspired by the GUMSHOE engine

- A historical setting that is grim but hopeful

- Magic where characters make ballad verses come to life

Ballad Hunters is the sequel to Shanty Hunters, winner of a 2022 Ennie Award (Judge’s Choice) and nominee at the Indie Groundbreaker Awards for Most Innovative and Game of the Year.

You can download the free early-access version of the game from DriveThruRPG or Google Drive.

–

Source: mostly ‘Stoning and Fire’ at Hillfort Entrances of Southern Britain by Michael Avery (World Archaeology, Oct., 1986), with some fact-checking against the site’s English Heritage website to make sure the dates and such hadn’t been overwritten by new testing methods.