In the early 20th century, an itinerant Daoist priest in the deserts of western China discovered a treasure trove of medieval documents, hidden for a thousand years behind a false door in an abandoned Buddhist temple. The discovery would give historians a corpus of documents they still use to this day – and the discovery and its aftermath make great inspiration for the gaming table.

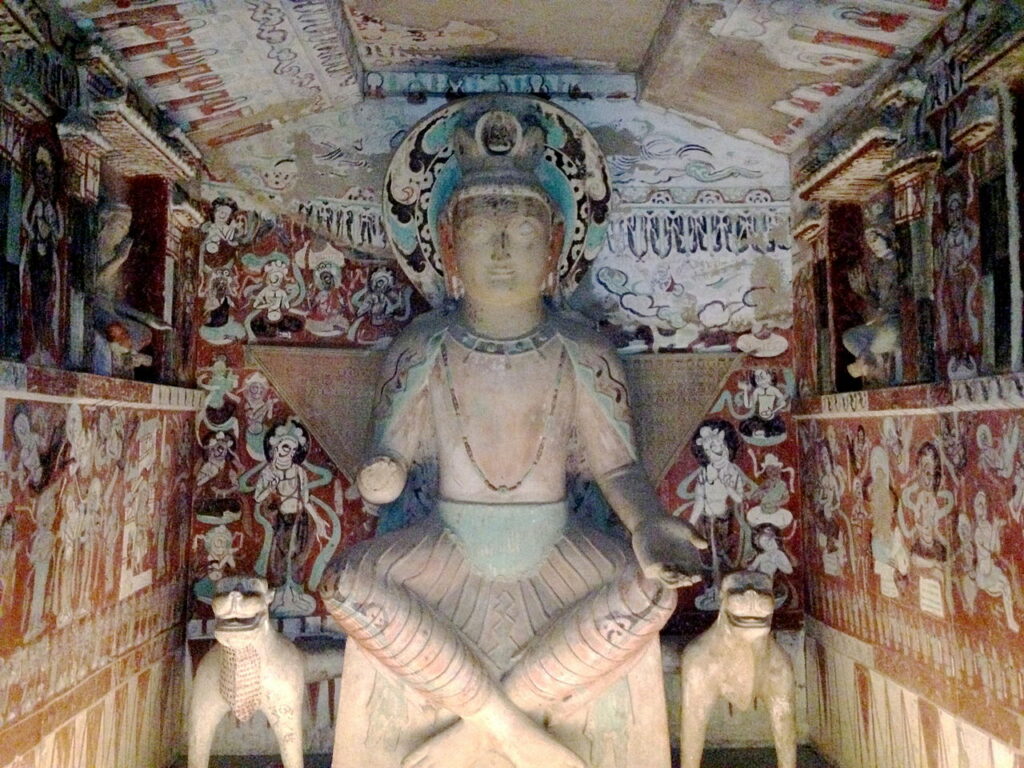

Our story begins in 1900 with Wang Yuanlu, an itinerant Daoist monk who had declared himself a Daoist priest and caretaker of several abandoned Buddhist sites along the old silk road in western China. One of these sites was the Mogao Caves outside Dunhuang, in Gansu province. The caves were full of beautiful wall paintings and clay statues of buddhas and bodhisattvas. At the time, though, the mouths of some of the caves had filled with sand. Wang was working to reopen them and was doing a little amateur restoration of the paintings inside.

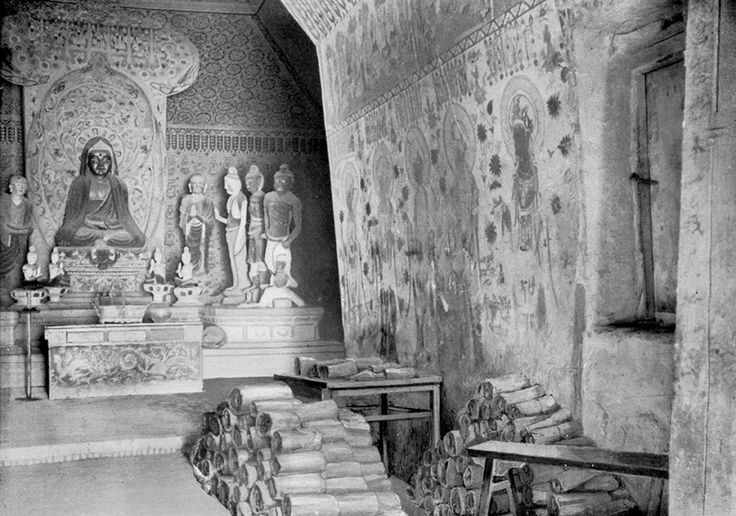

Wang noticed his cigarette smoke was being drawn through a nearby wall. Curious, he tore down the mud-plastered wall (destroying the paintings on it), and revealed a small cave, nine feet square, stacked ten feet high with rolled manuscripts. The space was so cramped, there was only room for two people to stand in it.

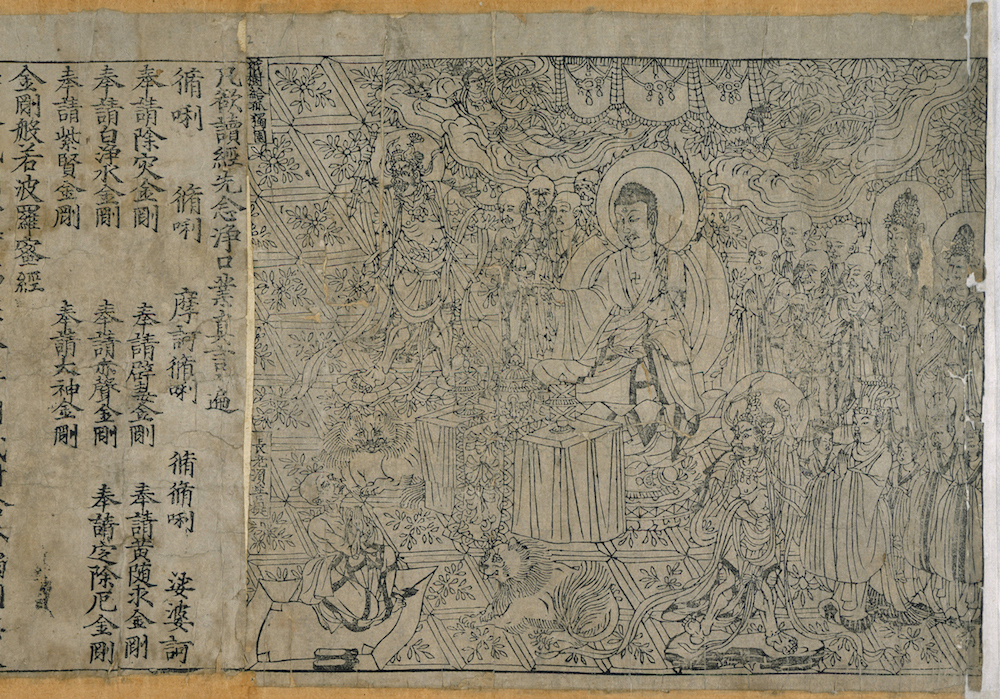

The find was remarkable. Tens of thousands of documents. Paintings on silk and paper. Sutras. Woodcuts. Textiles. Wooden sculptures. Most of the manuscripts were Buddhist, but there were also Daoist, Nestorian, and Manichean texts. The vast majority were in classical Chinese, but some were in Uighur, Sanskrit, Tibetan, and even the now-obscure languages Sogdian and Khotanese. It was like nothing Wang had ever seen before.

Wang sold off many of the manuscripts to finance the restoration of the artwork in the Mogao Caves. Some of these manuscripts reached the attention of two westerners in China: British explorer Aurel Stein and french Sinologist Paul Pelliot. Both traced these documents back to the Mogau caves. Stein arrived first, in 1907. He didn’t read Chinese and didn’t know much about what he was looking at, but he knew it would be valuable to western scholars. He bought a few thousand of what he saw as the best pieces from Wang. Pelliot arrived a year later and did much the same thing. Because Pelliot was one of the West’s foremost scholars of Chinese history and culture, his collection was better than Stein’s, even though Stein got there first. Later, Japan also sent an expedition to the Mogao caves to buy a share of the documents. Finally, the Qing government in Beijing took the rest – except for a stash of documents Wang had hidden elsewhere in the caves.

Since then, scholars have pieced together some of the history of the library cave. The Mogao caves were excavated in the 9th century, when the area was being fought over by the Tibetan Empire and the Chinese Tang Dynasty. The library cave itself was probably excavated to serve as the private meditation space of an important Buddhist monk named Hongbian. After his death, the monastery added a clay statue of Hongbian and a stele carved with his accomplishments. The statue was moved elsewhere in the caves before the library cave was filled with documents and sealed, but the stele was still there when Wang opened the place up.

The general consensus is that the library cave was sealed in the 11th century to hide its contents from invaders from one of the multiple Central Asian kingdoms that invaded China during that time. There is less consensus on why it was stocked in the first place. Stein’s original hypothesis is that the library cave was a dump for sacred garbage. When you had a scroll or a figurine that you didn’t need anymore, you want to ditch it, but you can’t just throw away something sacred – that would be blasphemous! So instead you put it in the library cave and forget about it. This hypothesis was pretty popular for about a century, but in 1999, Professor Rong Xinjiang of Beijing University’s ancient Chinese history department proposed that the library cave was actually a book repository created by monks from a lost monastery right outside the cave. This hypothesis proved contentious, and since I’m not an expert, I can’t begin to guess at how likely it is to be true.

The Dunhuang Manuscripts are great gaming content. Obviously, they make awesome treasure: stick ‘em in a dungeon, and your PCs can uncover this valuable (and memorable!) treasure trove. But you can also use them as a MacGuffin. In a heist game, the Chinese government may pay the party to steal back the disparate collection from France, England, and Japan. (See also the debate over reuniting the Elgin Marbles) Or, to put a really different spin on it, maybe the religious texts were placed in Hongbian’s meditation space to seal in his angry ghost. With the manuscripts gone, Hongbian’s shade has left the caves to wreak havoc. Only the reuniting the manuscripts can trap him again.