When Saumel Gobat, the Protestant Bishop of Jerusalem, died in 1879, an odd stack of papers was discovered among his effects. These were letters from the Ethiopian Emperor Sahle Dengel addressed to various Levantine and European powers, begging them for help with a peculiar and thorny problem. Judging by their text, Gobat was supposed to have delivered them, yet he clearly never did. The letters attended to the division of the Christian holy sites in Jerusalem among the religion’s different sects. They cast light on a curious kerfuffle, one which impacted Ethiopians particularly badly and which continues to cause trouble in Jerusalem to the present day. This division – especially as regards the Ethiopian church around 1850 – makes bizarre and memorable gaming material!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

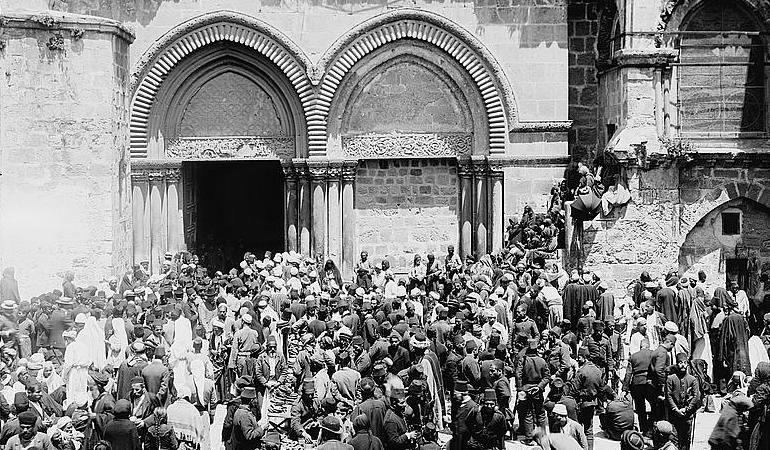

Image credit: israeltourism, released under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

As I’ve mentioned before, Ethiopia has been Christian since antiquity – longer than much of Europe. Until 1959, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church was subordinate to the Coptic (Egyptian) Orthodox Church. Ethiopia would ask the Copts politely to appoint them a bishop to run their church. Sometimes, the Copts would send an Egyptian south to Ethiopia to act as bishop for a time. Sometimes they’d forget. It wasn’t a great relationship. The Ethiopian, Coptic, and Armenian Orthodox Churches together comprise the Oriental Orthodox Churches, which are theologically distinct from the Eastern Orthodox Church (Greek, Russian, Ukrainian, etc.). Of the three Oriental Orthodox Churches, the Armenians were the wealthiest and most influential during this period, so they usually spoke to the outside world on behalf of their siblings in Egypt and Ethiopia. And, of course, the Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox Churches are both theologically distinct from the Catholic Church. I know this is a bit much, but I promise it’s about to matter!

The issue is this: all six churches (Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Armenian, Coptic, and Ethiopian) want to worship at the holy sites in Jerusalem, especially at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. That church includes both Calvary – the hill where Christ was crucified – and Christ’s empty tomb. Yet all six churches have different and conflicting rituals and traditions. How are they to share this space? Turns out the answer is “by arguing endlessly amongst themselves”. After the Ottoman Empire took Jerusalem, it fell to the Turks to mediate these disputes. A series of Ottoman proclamations, spread over several centuries, established an agreement called ‘the Status Quo’. The Status Quo laid out who owned what crypts and chapels, who could do which rituals when, and – most importantly – that any major changes to the Holy Sepulcher and several other sites had to be approved by all six churches. This agreement is still in effect today.

Image credit: Berthold Werner. Released under a a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Yet the Status Quo was malleable. It changed repeatedly over the centuries. Of interest to us is the fact that the Ethiopians couldn’t pay their taxes. To the Ottomans, the Holy Sepulcher was a license to print money. They taxed the monks, the priests, the pilgrims, everything. But Ethiopia was a long way away. No surprise the small Ethiopian contingent at the Sepulcher fell behind on their payments. So the Ottomans booted them out! The Ethiopian parts of the Sepulcher were given to the sects who could pay. This was in addition to other properties in and around Jerusalem the Ethiopians claimed to have lost in previous centuries. The Ethiopian contingent moved into the Monastery of the Sultan on the roof of the Sepulcher, which was already inhabited by Copts. The Ethiopians say the Ottomans gave them part ownership of the monastery as compensation for losing part of the Sepulcher. The Copts say they took in the Ethiopian monks out of charity. Either way, the Copts expelled the Ethiopians from the Monastery of the Sultan in 1820. This was definitely bad form, but whether it was illegal depends on whether you believe the Ethiopians or the Copts.

In 1838, an outbreak of plague killed the few Ethiopians in Jerusalem. The Copts got permission to burn the Ethiopians’ library on the grounds that maybe some plague might have gotten into their books. This destroyed all the Ethiopians’ titles and deeds of ownership. When the next Ethiopian contingent showed up, not only did they not have a customary right to a place to stay, they also lost their legal claim to it. It’s not clear to me where this new contingent lived. They might not have had an ancient and holy monastery, and were instead just living in a house. It does seem clear they were desperately poor, even starving. The Armenian Orthodox Church once gave the Ethiopians an allowance of food and clothes, but cut them off. While a bunch of monks living (and starving) together in a house does technically constitute a monastery, it quite defeats the purpose of having an Ethiopian presence in Jerusalem.

You’ll note no mention of the Protestants in all this. That’s because, as a relatively recent development in Christianity, they have no long, ancestral claim to any sites in Jerusalem. Nonetheless, there was a Protestant bishop in the Holy Land. By joint decree of England and Prussia, Samuel Gobat was the second Protestant Bishop of Jerusalem. His job was to represent the Anglican, Calvinist, and Lutheran branches of Protestantism in the Holy Land. As these churches exist outside the Status Quo, Gobat had little real power. What he did have were contacts – including a friendship with the government of Ethiopia, where he’d served two tours as a missionary. The first words he spoke in Jerusalem were to Ethiopians who’d come to meet him, delivered in their own language. This explains why, when Ethiopians were in trouble in Jerusalem, Emperor Sahle Dengel asked Bishop Gobat to help.

Six letters survive. One is addressed directly to Gobat, asking him to make the Armenians give the Ethiopians food. The others are addressed to the Ottoman Sultan, the Catholic Bishop of Jerusalem, the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem, and the head of property at the Armenian Monastery of St. James in Jerusalem. Each in turn asks the addressee to help the Ethiopian monastic contingent recover stolen property and right various wrongs. Each, out of politeness, omits the wrongs committed by the church of the addressee. The exception is the two letters to the Armenians, which explicitly say, “Resume giving our people food. What is wrong with you?”

That the letters remained in Bishop Gobat’s possession implies he never delivered them. Let’s not be too cruel to him. He was known in his day for repeatedly intervening on behalf of the destitute Ethiopian contingent. It’s entirely possible he read the letters and decided they’d be counterproductive. He may have thought that, being on the ground, he knew more about the situation and what would actually help – certainly more than some far-off puppet emperor.

In the second half of the 19th century (after the period in question) it came to be believed that the title deeds had not been burned, but were back in Ethiopia. The Russians in particular took an interest in this idea, since supporting it gave them a pretext to back Ethiopia against its rival Britain. These deeds never appeared, and the Ethiopians later claimed they’d been purchased by a Russian living in Ethiopia, one Baron Nicholas Chef d’Oeuvre, and who knows where the supposed deeds were now?

The Status Quo is still in effect today, albeit with some changes. The Ethiopians are back in the Monastery of the Sultan. The Assyrian Church has been added to the Sepulcher. The Protestants are still out; the spirit of ecumenism extends only so far. Affairs remain contentious. Since repairs require the assent of all factions, the Holy Sepulcher is looking a bit run-down. Someone invariably has a complaint about any given repair, so nothing gets done. A ladder has remained on a roof since at least the 1700s because folks can’t agree whether to remove it. In 2002, a chair was moved into the shade on a hot day. The resulting brawl put eleven people in the hospital. In 2008, someone left a door open during a procession, triggering a police intervention to break up another brewing fight.

At your table, you might have your PCs encounter letters like the ones Bishop Gobat never delivered, maybe stumbling upon them in a dead woman’s effects. They lay out a situation where a small foreign contingent in the holiest city in your fictional setting are abandoned and starving because their coreligionists do nothing but rob them. Any heroic PC should immediately wonder: is this still happening? Your fictional version of Bishop Gobat never delivered those letters, but maybe your PCs can. If they can use those letters to embarrass enough powerful people, maybe they can right a tremendous wrong in an ancient and holy place!

Step one for the GM is to decide how many of the addressees are still alive and to flesh out the surviving addressees and the successors of the dead ones. Create a network of antipathy among them based on the old dislikes in the real-world situation. Figure out who can be pressured (and by whom), who can be bribed (and with what), and who would be flat-out embarrassed enough by these revelations to shape up and fly right. Then thrust your PCs into this explosive political mixture, and watch them step on toes and put their feet in their mouths for a few sessions!

–

Sources:

Letters from Ethiopian Rulers (Early and Mid-Nineteenth Century) (1985)

The Status Quo in the Holy Places by L.G.A. Cust (1929)