This blog mostly talks history and folklore (and sometimes science), but this week we digress into geometry and literature: Edwin A. Abbott’s 1884 novella Flatland. The book’s first half is a combination of social satire and speculative fiction, describing a society of talking shapes that inhabit a purely two-dimensional world. The second half recounts a Flatlander’s journeys beyond his literal ‘plane’ of existence. This Victorian novella suggests a delightful approach to the fantasy and science fiction trope of travel to other worlds!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

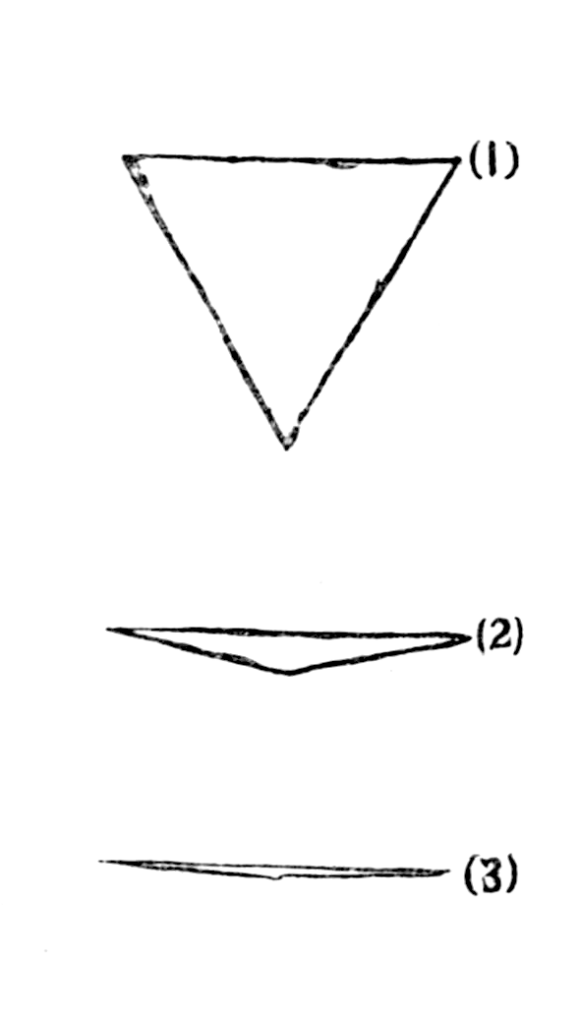

We are introduced to the world of Flatland by our guide, Mr. A. Square. Flatland is a perfect plane. The people who live there are flat shapes: squares, circles, triangles, lines, etc. Their social system mirrors that of Victorian England, but exaggerated for satirical effect. Because the people of Flatland view each other head-on, all they see of one another is lines of differing lengths, just like how if you put a credit card on a table and lower your head to view it edge-on, you see only a thin line. To tell one another apart, Flatlanders must watch each other rotate and see how the length of the line changes (rotate the credit card slowly, and see how its perceived length shrinks and grows). No one in Flatland has any idea there is such a thing as ‘up’ or ‘down’, but just north, south, east, and west across their limitless, flat plane.

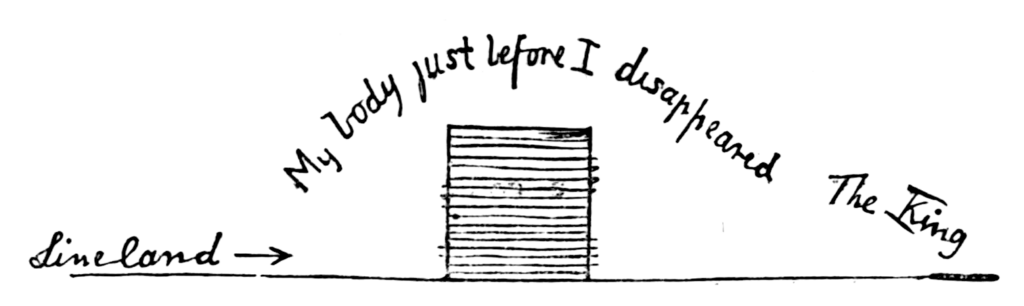

Then, in a dream, Mr. A. Square travels to Lineland, which consists of a single, endless axis. The people there know north and south, but not east and west. All Linelanders are either lines or points. Because they can’t step around each other, the person north of you and the person south of you will be your neighbors until you or they die. Worse, they appear to you only as a single point to your north and a single point to your south. You can only see how far they are by their brightness. Mr. Square meets with the King of Lineland – the longest line of them all, a whopping six inches – but is unable to convince him of the existence of east and west. The Linelanders cannot perceive this dimension; they can’t even imagine it. Indeed, Mr. A. Square appears to the King of Lineland to be a line or a point (for, to a Linelander, the two are visually indistinguishable) existing only where the plane of Mr. Square’s body crosses the line of the Linelanders’ widthless world.

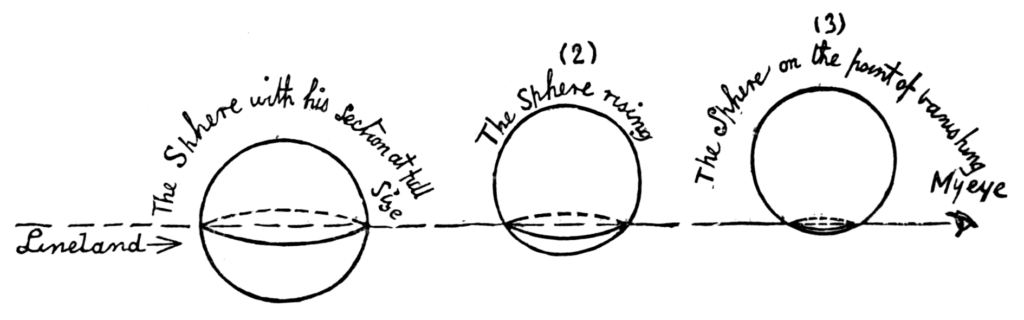

The next day, Mr. A. Square is visited by a Sphere from Spaceland. The Sphere believes Mr. Square is ready to learn the truth of the Third Dimension: that there exists also ‘up’ and ‘down’, though Mr. Square has no way to perceive it. To prove the claim, the Sphere passes vertically through Flatland, first appearing as a single point, then growing to a small circle, then a wide circle as the Sphere’s midsection crosses the plane of Flatland, then diminishing to a small circle and a point again. The Sphere then takes Mr. Square on a tour of Spaceland and even a brief visit to the solitary oneness of Pointland. When Mr. Square returns from his journey, he tells everyone he can about the miracle of the Third Dimension and is locked in an asylum as a heretic, a traitor, and a madman.

(Now is as good a time as any to acknowledge that, for all that Abbott tries to make his universe sound plausible, it was already behind the math and physics of his day, which acknowledged time as a one-directional dimension. Abbott was a theologian, not a physicist.)

This all brings us to the traditional fantasy and science fiction trope of travel to other universes: the planes in D&D, the Nine Worlds in Norse mythology, the Mirror Universe in Star Trek, or the worlds of the Narnia series. All these takes have their idiosyncrasies. But the Flatland version is particularly fun because of what it implies about the setting and how easily it can be added to an existing campaign.

If we take Flatland’s version of layered multiverses and extrapolate it to our own three-dimensional world, what do we get? First, let’s look at a dialogue between Mr. A. Square and the King of Lineland.

KING: And let me ask what you mean by those words “left” and “right”. I suppose it is your way of saying Northwards and Southwards.

SQUARE: Not so. Besides your motion of Northwards and Southwards, there is another motion which I call from right to left.

KING: Exhibit to me, if you please, this motion from left to right.

SQUARE: Nay, that I cannot do, unless you could step out of your Line altogether.

KING: Out of my Line? Do you mean out of the world? Out of Space?

SQUARE: Well, yes. Out of your World. Out of your Space. For your Space is not the true Space. True Space is a Plane; but your Space is only a Line. If you cannot tell your right side from your left, I fear that no words of mine can make my meaning clear to you.

A remarkably similar dialogue occurs between Mr. Square and the Sphere, where the shoe is very much on the other foot.

SQUARE: Would your Lordship indicate or explain to me in what direction is the Third Dimension, unknown to me?

SPHERE: I came from it. It is up above and down below.

SQUARE: My Lord means seemingly that it is Northward and Southward.

SPHERE: I mean nothing of the kind. I mean a direction in which you cannot look, because you have no eye in your side.

SQUARE: Pardon me, my lord, a moment’s inspection will convince your Lordship that I have a perfect eye at the juncture of two of my sides.

SPHERE: Yes, but in order to see into Space you ought to have an eye, not on your Perimeter, but on your side, that is, on what you would probably call your inside; but we in Spaceland should call your side.

SQUARE: An eye in my inside! An eye in my stomach! Your lordship jests.

If we bring this idea to the three-dimensional space the PCs inhabit, it’s clear they would not be able to perceive a fourth dimension any more than the King of Lineland could perceive the second or Mr. Square could perceive the third. The PCs lack the faculties needed to look in that direction. But while they will never be able to perceive the fourth dimension, a four-dimensional being could give them a device permitting travel through the fourth dimension, just as the Sphere carries Mr. Square around through the third.

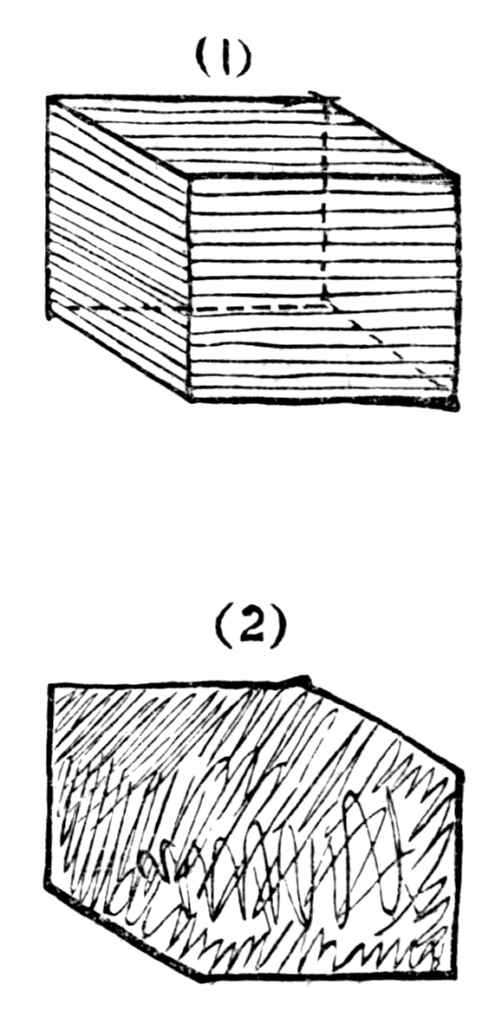

What would this fourth dimension be? Just as a square is a whole bunch of lines piled one atop another and a cube is a whole bunch of squares piled one atop another, this fourth dimension would be a whole bunch of three-dimensional universes piled one atop one another. For convenience, let’s assign each world a letter, stacked in alphabetical order, with A on the ‘bottom’ and Z on the ‘top’, and the default universe of the campaign setting somewhere in the middle.

If you’re in universe A and move in the direction of the end of the alphabet, you wind up in B, then C, then D. Move back towards the beginning of the alphabet and you pass through C, then B, then return to A. If you start in A, move to B, walk two feet to the left, then move back to A, you wind up two feet to the left of where you started from. In your campaign, you get to choose what universes are stacked in what order. For a D&D example, you might have A be the Abyss, B be the Beastlands, C be Carceri, and D be the Demonweb Pits.

In order to be playable, the topography of all these stacked universes should be more or less the same. Otherwise, you might move towards the end of the alphabet from A and find yourself in B a mile underground or a mile in the sky. Similar topography is great, because it sets up the opportunity for symbolic symmetry. If the same confluence of rivers exists in every universe, there’s probably always a city there. Each version of that city could emphasize different features. London in Hell might always be in the midst of the Great Fire of 1666. London in Faerie might be the court of King Oberon. London in the Shadowfell might be gloomy and vacant, like it was during the Plague, only more so.

In Flatland, if there exists a fourth dimension, there exist four-dimensional beings of whom almost all three-dimensional beings are unaware. Mr. A. Square asks the Sphere about them. The Sphere admits he doesn’t know much, but it’s suspected that four-dimensional kidnappers are behind the occasional mysterious disappearance of three-dimensional people. Four-dimensional beings in a Flatland-style cosmology would have these traits:

First, a four-dimensional being definitionally exists in multiple three-dimensional universes simultaneously. As she moves between universes, different parts of her will be in your universe at different times. The effect of this will be that she seems to change. Just as the Sphere passing through Flatland started as a point, then grew to a small circle, a large circle, then shrank back down again, so too will a four-dimensional being seem to alter as she passes through your universe. Maybe her colors flicker. Maybe she sprouts tentacles or horns, which then disappear. On the other hand, if she’s standing still and you’re moving between universes, she will change but nonetheless still exist in adjacent universes, even though all the people, buildings, trees, etc. of one universe will blink out of existence and be replaced in the next.

Second, given time, four-dimensional beings can go anywhere and see anything they want in three-dimensional space. By way of analogy, the Sphere can sit above Mr. Square’s house, invisible to the Flatlanders, and see inside locked boxes and even inside Mr. Square’s own stomach. If the Sphere wanted to see inside the sealed home of Flatland’s Chief Circle, he could, provided he was willing to fly over there. Similarly, a being that can see the fourth dimension would be able to sit in universes A through D and peer into universe E (or maybe even all the way to universe Z!). She could go anywhere and see anything, as long as she was willing to take a little time to do it.

Third, four-dimensional beings can kill anyone they want, completely invisibly. By way of analogy, the Sphere at one point gives Mr. Square a gentle poke in his center from above. Mr. Square feels pressure in his stomach coming from seemingly nowhere at all. If a four-dimensional being wants you dead, she can reach into your insides from another universe and rip them right out. You’re toast as soon as she finds you.

Mr. Square speculates about the existence of dimensions beyond the fourth, dimensions of which the Sphere cannot even speculate. If five-, six-, or seven-dimensional beings exist in your campaign world, their capabilities are so far beyond those of the PCs, they must surely be, by any reasonable definition, gods. If you reveal the existence of four-dimensional beings in your campaign world, it probably won’t take the players long to speculate that every god their characters ever heard of was actually a high-dimensional being. Such entities would be beyond the ability of even four-dimensional beings to conceive, just as the King of Lineland would not be able to comprehend the nature of the Sphere.

Flatland ends on a warning note. Mr. Square is arrested for preaching the heresy of the third dimension and writes his little book inside an insane asylum. It turns out the Sphere isn’t the first three-dimensional prophet to visit Flatland. The government’s senior ministers are well aware the third dimension exists and fear social unrest would result if word got out. I love this idea! Having extra-dimensional travel be secret and forbidden makes it feel special. The planes aren’t a place to jaunt off to when your D&D character hits 15th level. They’re dangerous, and just traveling there could get you locked up!