In 1883, the Jicarilla Apache nation was forcibly moved from land they’d been promised as their reservation to the reservation of a sister nation, that of the Mescalero Apaches. Neither group was happy with this state of affairs. Three years later, the Jicarilla Apaches snuck out of the Mescalero reservation in a blinding blizzard to return to the land they’d been promised. It’s a wild story, and very gameable!

Also, we wrapped up Gen Con a few weeks ago, making it time for my annual year-in-review. This marks four years of the Molten Sulfur Blog – all without ever missing an update. This was my best year yet! I’ll dig more into the details of that at the end of this post.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Image credit: AwBaseball25. Released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

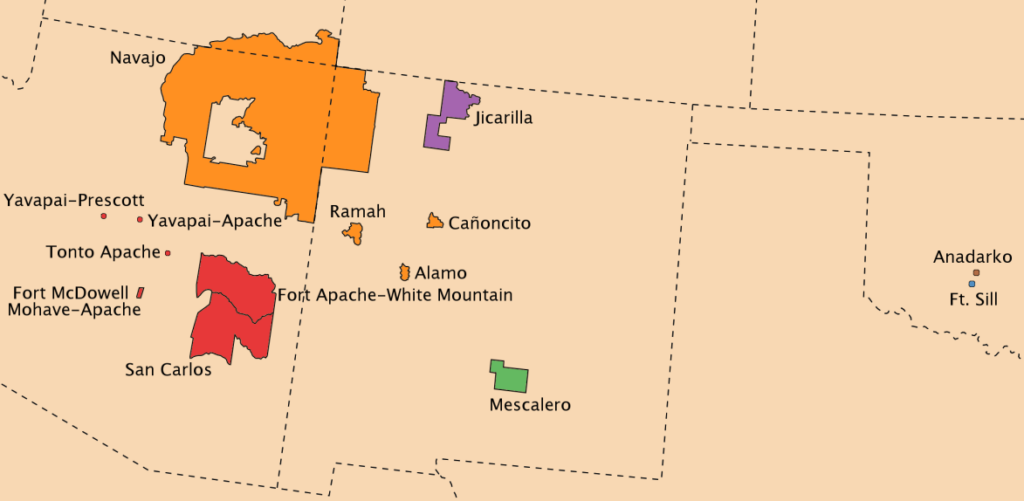

The Jicarilla Apache nation was initially less affected by white settlement than many of its neighbors. Jicarilla lands – roughly the area bounded by the Pecos, Chama, Canadian, and Arkansas rivers in modern northeast New Mexico and southeast Colorado – were claimed by Spain, then by Mexico. The terrain wasn’t well-suited to European agricultural practices, and there was always somewhere better in Mexico for settlers to take over. The Jicarilla were mostly spared. That changed after the Mexican-American war. White settlers flooded into these newly-conquered American territories. Six years of genocidal war followed (1849-1855). Half the Jicarilla nation either starved or was shot by federal troops, cowing the Jicarilla’s will to fight and driving them from their sacred lands to foreign soil around two ‘agencies’.

The Jicarilla lived in legal limbo around the agencies for 25 years. They were not granted any tribal territory, but neither were they permitted to homestead (unlike many plains-adjacent nations, the Jicarilla were accomplished farmers). When they went to hunt, settlers complained to the Army that Indians were encroaching on their land. If they improved the land with dams or fields, white settlers claimed that land and took over their farms. The agencies offered a federal food dole, but it was irregular and insufficient. A reservation is a lousy consolation prize, but the hope of one was all the Jicarilla had. Their larger and more powerful neighbors, the Mescalero Apache and Ute nations, could command the attention of territorial governors and got reservations, but the Jicarilla were too few and too weak to pose a threat.

In 1880, the Jicarilla were finally moved onto a reservation of their own. The land was lousy compared to the sacred lands to which they could never return, but it beat starving. Except Congress never ratified the new reservation. Once again, the Jicarilla were too unimportant to command attention. Settlers started eying land on the Jicarilla reservation. The governor of New Mexico could hear the pressure of these settlers, but not of the Jicarilla; Indians couldn’t vote. In 1883, the Jicarilla were ordered to resettle on the reservation of their sister nation, that of the Mescalero Apaches. Jicarilla leaders weighed launching a surprise attack in lieu of moving, but decided that would scuttle any hope of ever returning to their reservation. They packed their bags and moved.

On the Mescalero reservation, neither Mescalero nor Jicarilla were happy about having to share. What little decent farmland existed was already claimed by the Mescaleros, and there wasn’t room or supplies for the Jicarillas anyway. It was a bad existence for both made worse by the presence of the other. There were only a few hundred Jicarilla left: 107 households in all.

It’s here that we introduce three important Jicarilla headmen: Augustín Vigil, Augustine Velarde, and José Martínez. Vigil was an established leader among the Jicarilla. He’d met with President Hayes in 1879 in Washington, D.C. and was one of five who negotiated with the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to decide the location of the 1880 reservation. Velarde was a young man and new to leadership. He was the brother of a long-established headman who’d stepped back and let Velarde take over leadership of his band in early 1886. I wasn’t able to turn up much on Martínez.

In late 1886, these three men set in motion an evolving scheme to get their people some land. First, they petitioned the government to let the Jicarilla sever their formal tribal affiliations and homestead the same way Mexican settlers were permitted to. The response was that those three headmen (plus another, Vicenti) could homestead with their families and maybe, if it worked out, the rest of the Jicarilla could follow suit later. The headmen made a compromise counter-offer. Before the vast and grinding bureaucracy could slowly respond, some 200 Jicarilla Apaches left the Mescalero reservation in October of 1886. They rode north towards their former reservation. Along the way, they stopped at the villages of their friends at the Ohkay Owingeh and San Ildefonso pueblos. The military caught up with them there. Mercifully, there was no massacre. Instead, everyone agreed the Jicarilla could stay at the pueblos for now while this business was hashed out. But now the Jicarilla were split in two: half on the Mescalero reservation and half in the pueblos.

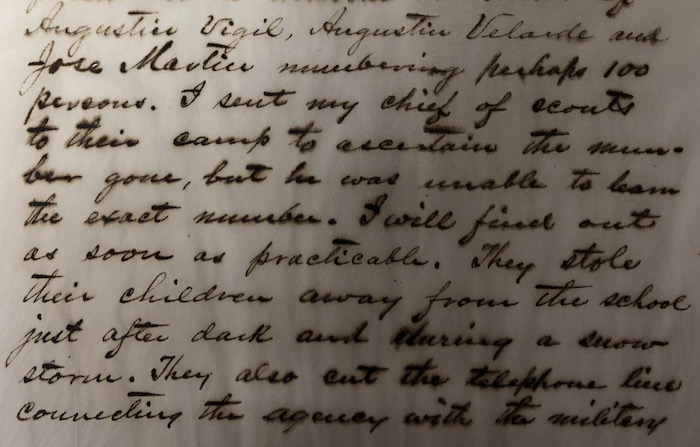

Vigil, Velarde, and Martínez decided to reunite their people and reinforce their hand by moving their bands off the reservation and up to the pueblos. In November of 1886, the Jicarilla bands led by Vigil, Velarde, and Martínez left the Mescalero reservation. They timed the departure carefully. They left just after dark, in the middle of a violent blizzard. As they went, they cut the telephone lines between the Mescalero agency and the military post at Fort Stanton. That way, even after their departure was noticed, the reservation agent couldn’t send the Army after them until they were already away. (Note that it’s telephone, not telegraph – the agent’s letter to D.C. is unambiguous.)

The biggest coup of the departure was handling the children. There was a residential school on the Mescalero reservation, and almost all the children – both Mescalero and Jicarilla – attended. Jicarilla parents were understandably unwilling to leave without their kids. Presumably, Jicarilla adults must have broken into the school dormitories after hours, separated the Jicarilla kids from the Mescalero ones, and made their escape – all without alerting any of the school’s live-in staff, for no alarm was raised.

At your table, that’s the part I’d focus on! Breaking a select group of kids out of an evil school in the middle of a darkened blizzard? Knowing that if you are caught, a much larger escape plan may be unraveled? Those are high stakes! Throw in some uncooperative children, a nosy dorm matron, a kid who’s sick, and maybe a monster lurking out in the snow, and you’ve got yourself an adventure!

For closure, the Mescalero got what they were so desperate for. In February of 1887, President Cleveland signed an executive order making the Jicarilla reservation from 1880 official, and the Jicarilla were resettled by springtime. This inaugurated the next generation of trouble for the Jicarilla nation, but now at least they had land.

Image credit: Ish ishwar. Released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

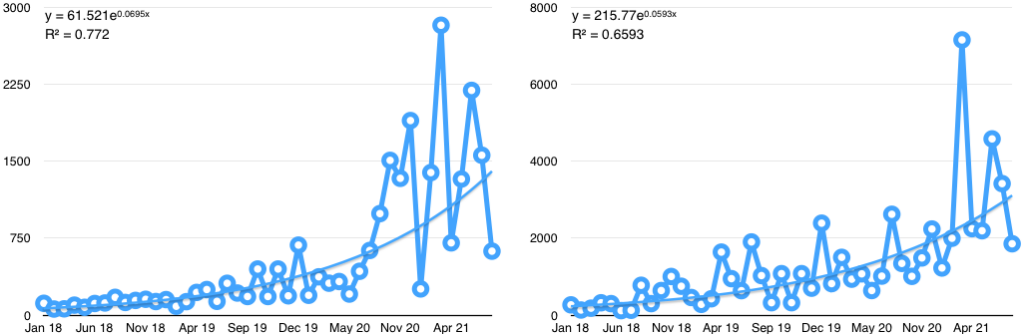

This past August marked four years of the Molten Sulfur Blog, and the most recent year has been the best! Readership a little more than doubled. This is consistent with previous years’ growth in readership, save that I started year four with perhaps 600 regular readers, so doubling it isn’t just a big relative increase, but also a big absolute increase. Obviously, stats are super finicky and everything depends on how you establish your definitions. But today, the Molten Sulfur Blog probably has somewhere between 1,000 and 1,500 readers.

This growth in readership is reassuring. For one, every writer likes being read. But more importantly, someday I’d like to transition to writing RPG content full-time, and growing the readership of this blog strikes me as the best way to do that. The more people who know the Molten Sulfur brand and say “Yeah, that Molten Sulfur guy does good work. I’ll shell out some money to back his Kickstarter,” the sooner I can make that transition without sweating my mortgage payments. Obviously, the Patreon is also a big part of that. My current patrons comfortably cover my research and web hosting costs, and I’m very grateful to them!

Still, I worry about how dependent my readership numbers are on Reddit. See those graphs below? What specific metrics they’re tracking matters less than how jagged they are. The months showing big spikes are entirely due to one or more blog posts blowing up on the subreddit r/rpg. The valleys are months when all my content was downvoted to oblivion. If r/rpg ever tires of me or if Reddit ever rolls out an attention algorithm like the other social media networks have done, it’ll set back my readership something major.

To prevent such an occurrence from affecting you, might I recommend subscribing to my weekly email newsletter? It’s little more than a link to this week’s blog post that arrives in your inbox every Tuesday. Reddit is fickle and algorithms uncertain, but if you sign up for the newsletter and train your inbox to actually show it to you, you’ll never miss a post! On desktop, the newsletter sign-up box is on the left side of the screen (you might have to scroll up a bit to see it). On mobile, your best bet is to use the contact form. Just write ‘Newsletter’ in the subject and message fields (or something to that effect) and I’ll add your email address to the list.

I wasn’t nominated for an Ennie Award this year. I was a bit disappointed, since I was nominated the previous two years and I believe my content is better now than it was then. But a lot of regular nominees were missing this year! The podcasts Ken and Robin Talk About Stuff, Plot Points, and Red Moon Roleplaying were absent despite being staples of the nominee list for years. Reliable multi-nominee-producing companies Pelgrane Press, Magpie Games, and Chaosium Inc were also missing. And while publishers in the Indie Game Developer Network are usually well-represented at the Ennies, this year they weren’t (with the notable exceptions of The Maze from Axo Stories and Arium by William Munn – very well-deserved, Alastor & friends!). Ditto for products coming out of the OSR scene. I don’t know any inside baseball about what the judges’ priorities were this year, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they decided it was time to shake up the field a little. And if that means some new faces with cool new ideas get some exposure, I certainly can’t complain!

I was at Gen Con 16-19 September and ran four sessions of Shanty Hunters. I didn’t mention it on the blog ahead of time because I didn’t want to accidentally encourage anyone to attend a convention in the middle of a pandemic. My reason for going was to work the Indie Game Developer Network booth, since I was afraid what might happen if we didn’t get enough volunteers. I expected the con to be a weird, hollow shell of its usual self; I’ve rarely been happier to be wrong. I had a great time! I even met some regular blog readers – guys, it was so wonderful to meet you! You’re awesome, and I hope we get to game together again soon. 🙂 Most importantly, as of this writing I’ve tested negative for COVID. Almost everyone at the con seemed to take masking seriously and I met no one who reported being unvaccinated.

Writing the Molten Sulfur Blog remains a source of immense joy. I do it because I love it, not because it’s a sensible side hustle. It gives me a reason to read interesting books, to practice my writing, and to produce material that – I hope – entertains and informs. Thank you so much for another amazing year. You – all of you – rock!

Sources:

The Jicarilla Apache Tribe: A History by Veronica E. Velarde Tiller (yep, that’s the same last name as one of our three headmen, and no, that’s not a coincidence) (1983/2000)

Letter from Fletcher J. Cowart to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, November 18, 1886, Mescalero Agency, kept at the National Archives at Denver, Record Group 75, Miscellaneous Letters Sent 1886-87. Thanks to archivist Cody White for scanning me a copy!