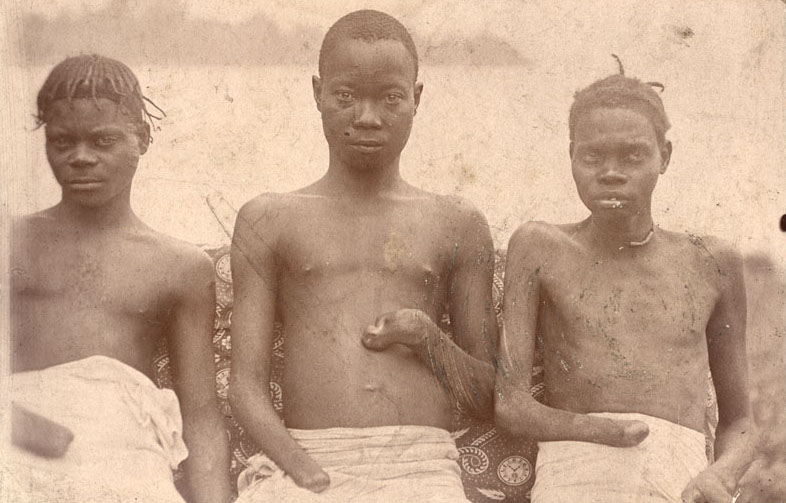

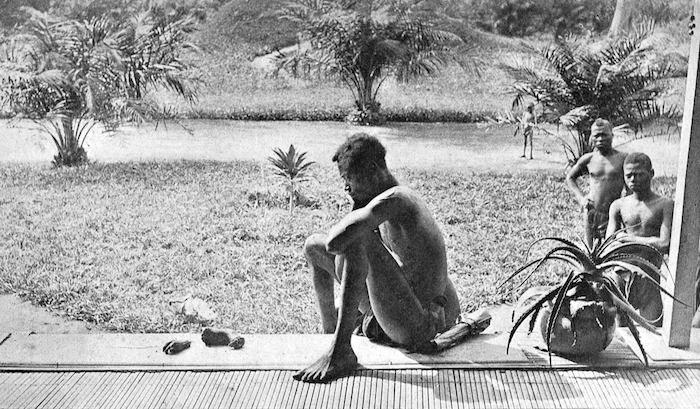

Leopold II, King of the Belgians, was one of history’s greatest mass murderers. Not in his own country, where he was a fairly benign ‘builder king’, but in the Congo, which he ran as his own personal colony, answerable only to him, and whose profits went directly into his private bank account. The tactics he used to squeeze ivory and rubber profits from his grand business venture – massacres, hostage-taking, slavery, and working entire populations to death – so ravaged the Congo that its population at the end of his reign of terror was only half of what it had been at the beginning (about ten million deaths).

To acquire his colony and to conceal what his employees were doing, Leopold had to manage an immense, evil, and brilliant public relations organization. He employed a metaphorical army of lobbyists, journalists, and lawyers. He used censorship, bribery, and intimidation to keep news about his Congo business from reaching the ears of the public. King Leopold’s PR machine makes an amazing template for a villain in an investigative RPG.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

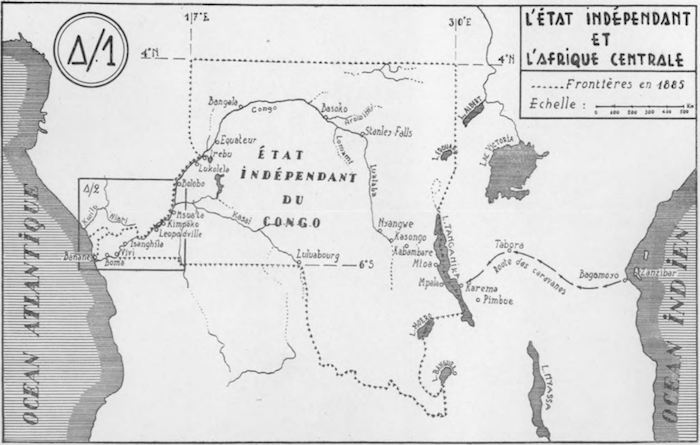

In 1879, the Congo was still under the control of its indigenous rulers. King Leopold meant to change that, but he had to do it quietly. He wanted to build roads and ports to open up the interior of the country to exploitation, but he had to hide who was doing it. As the sovereign of tiny Belgium, he couldn’t be seen taking control of the enormous Congo. Yet.

Three years earlier, Leopold organized the creation of (while making it seem like he’d been pressured into joining) the International African Association. The group was ostensibly a philanthropic organization, but in truth it was a legal fiction. Its members were prominent explorers and geographers, but they only met once and the group didn’t do anything. King Leopold also formed a group called the Committee for Studies of the Upper Congo, but its members were businessmen and bankers, and the majority of the shares were held by proxies for Leopold. The Committee would dissolve within a year, but Leopold continued to act like it existed. The ports and roads he was building in the Congo were publicly under the control of these two non-existent organizations, which created a buffer between Leopold and his as-yet-unformed colony.

To add to the buffer, Leopold created a third organization, the International Association of the Congo. It was intentionally named confusingly similar to the International African Association, the ostensible philanthropic association of geographers and explorers. The new International Association of the Congo even used the same flag as the old International African Association: a gold star on a blue background. Apparently, no one cottoned on to the two organizations being different. That suited Leopold fine, because it let him consolidate his organization under one metaphorical roof that he controlled absolutely. The new International Association of the Congo was wholly controlled by Leopold. Not by the Belgian government or the Belgian Crown, but by Leopold the man, the private citizen.

What was the stated goal of the International Association of the Congo? It depended on the audience. To Americans, the organization presented itself as a confederation of free indigenous republics, which would soon select a president who would live in Brussels under the watchful eye of King Leopold. To the less-Federalist, more-military German audience, it was a military organization fighting for righteous causes in the Dark Continent, not unlike the Crusaders of old. To the charity-minded British audience, the Association was establishing a chain of hospitals and scientific outposts intended to render service to the locals. Whatever that nation wanted to hear, Leopold, via the Association, fed it to them.

Meanwhile, the Association’s employees in the Congo compelled local chiefs to sign treaties handing over rights to their land and agreeing to provide labor to the Association. Unsurprisingly, this was accomplished by a combination of trickery, bribery, and force. With a road built and the treaties in place, Leopold was ready to get to work. But before he could do that, he had to protect his claim against rival colonial powers.

Leopold had to get other nations to agree that the International Association of the Congo was a lawful sovereign state. He hired some fancy lawyers to find justification and precedent for a private company (which the Association was) to be treated as a country. And since if one nation recognizes a new country, most other nations fall in line, Leopold only had to find one sucker. He set his eyes on the United States.

Leopold’s lobbyist in this effort was a wealthy Connecticut expatriate, Henry Sanford. Sanford had been living in Belgium for some time. Like many Americans, he was entranced by royalty. King Leopold easily flattered, wined, and dined the gullible Sanford into taking up the cause. Sanford was a long-time Republican donor, and American President Chester A. Arthur was a Republican. Sanford invited Arthur down for a wonderful vacation at his estate in Florida. He paid for pro-Association puff pieces to be printed in American newspapers. Sanford even won over the U.S. Congress by convincing the racist head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that America’s black citizens could be shipped to the Congo.

In 1884, the U.S. State Department recognized Leopold’s claim to the Congo in a confused statement that mentioned both the old International African Association and the new International Association of the Congo. While the confusion suited Leopold fine, the ambiguity did not. So he just unilaterally changed it. When Leopold quoted the American document in later publications, he edited it so it only mentioned the new International Association of the Congo. It was a lie so bold that who would think to question him on it? Other nations soon fell into line, and the Congo became Leopold’s de facto personal property.

From 1885 on, Leopold dispensed with the Association and ruled the Congo directly as the ‘Sovereign King’ Leopold I of the Congo Free State. Leopold mostly kept news about what was going on in his private colony out of the newspapers. The only Westerners permitted into the Congo were employees of the Free State, subordinate corporations, the Catholic Church, and Protestant missionaries. This last group would prove difficult, as Leopold had no real control over them. He encouraged Protestant missionaries to bring complaints to him directly so he could resolve them, rather than going to the press. He also imposed taxes and legal headaches on uncooperative missions. Most missionaries toed the line. But word did eventually leak out as word usually does, and there started to be rumblings of international criticism. Bad for business!

So in 1896, Leopold appointed six clergy members – three Catholic, three Protestant – in the Congo to form a ‘Commission for the Protection of the Natives’. Of course, none of the six were headquartered in rubber-producing areas where the real atrocities were happening. The Free State set aside no funding for the commissioners to travel to investigate anything or meet with one another. All six were handpicked for their loyalty to the King. And even if they did conclude something, they only had the legal authority to inform, not to enact any changes. The commission met only twice (each time with a quorum of only three members). But the existence of this sham committee was a public relations coup for Leopold, and criticism of the Congo Free State soon disappeared from the papers.

The issue came to a head in 1904, when Roger Casement, an officer of the British Consulate in the Congo, wrote a report on the abominable humanitarian situation there. Leopold marshaled two of his better-placed lobbyists. The King’s considerable charm had won over Constantine Phipps, the British Minister to Brussels. Phipps got the British Foreign Office to delay publication. Sir Alfred Lewis Jones lobbied the Foreign Office to soften the report; Jones was the head of a British shipping line that enjoyed a monopoly on shipping to and from the Congo. There wasn’t much that could be done to soften the report; its author, Casement, was giving interviews with the press, and it would be embarrassing if the report omitted information Casement had already publicized. Still, the Foreign Office replaced all the names in the report with fictionalized initials, which reduced its specificity and made it less powerful. Leopold also used the newspapers he controlled (or had influence over) to issue lengthy rebuttals to Casement’s report.

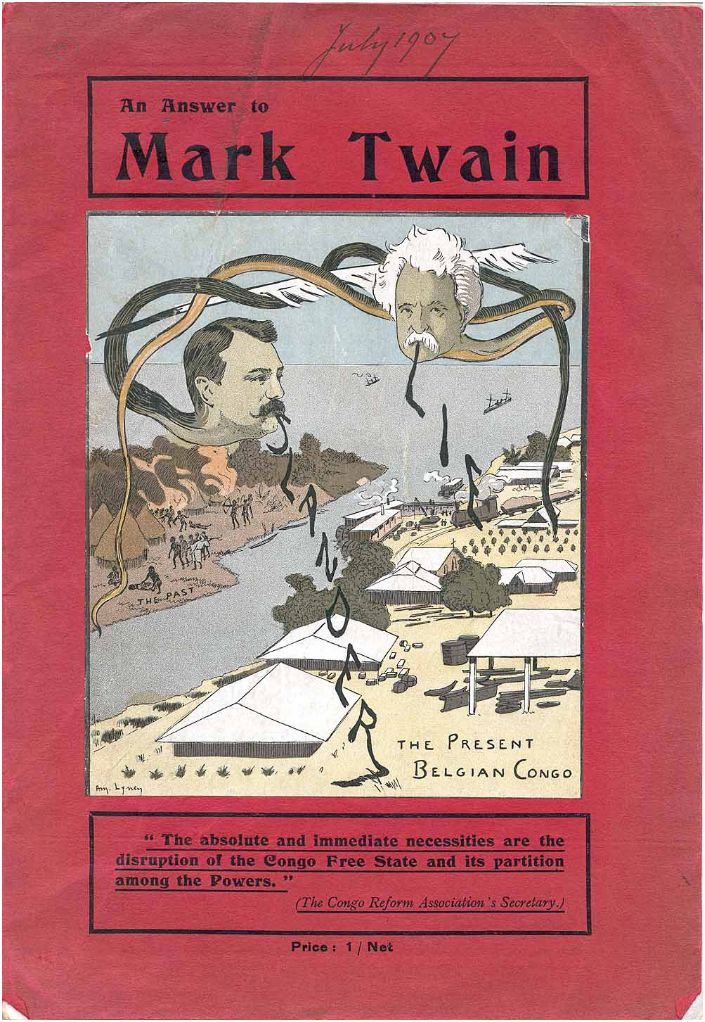

In 1904, Leopold established a secret press bureau to cover up the revelations that were increasingly coming to light. As with the International Africa Association, he used a series of front organizations to obfuscate the press bureau’s degree of centralization: the ‘Bureau of Comparative Legislation’ in Brussels, the ‘Committee for the Protection of Interests in Africa’ in Germany, and the ‘Federation for the Defense of Belgian Interests Abroad’ with branches in many countries. The secret press bureau produced books, bankrolled newspapers, and found credible patsies to put their name on pamphlets. It dispatched investigators to the colonies of the other imperial powers to find scandals and atrocities in their houses to muddy the waters. And it bribed editors and journalists at papers across Europe and America to make anti-Congo Free State articles simply disappear. Reporters who wouldn’t play ball could be blackmailed. Leopold personally exposed an uncooperative French journalist’s affair to the reporter’s wife.

Leopold also leaned on Sir Alfred Lewis Jones, the vulnerable shipping magnate, threatening to take away his monopoly on the Congo trade. Sir Alfred dutifully provided credible patsies to travel all across the Congo on carefully-curated tours. When the patsies returned home, they published books reporting they saw no atrocities and that there were strict laws in place against abuse. These laws, of course, were never enforced. Most Free State employees probably weren’t even aware they existed. Leopold then paid one of these ‘useful idiots’ to stay in London and lobby members of the British Parliament on his behalf.

Leopold also created a network of cronies in America. Chief among these was Senator Nelson Aldrich, a Washington power broker and chair of the Senate Finance Committee. By offering lucrative concessions in the Congo to Aldrich and his wealthy business associates, Leopold got Aldrich to torpedo any efforts by the U.S. government to complicate the Congo Free State’s activities. Leopold’s American network also included Professor Alfred Nerincx, who got pro-Congo Free State articles into highbrow magazines; Frederick Starr, a racist anthropologist who wrote fifteen articles and a book for Leopold; Lawyer Henry Wellington Wack, who also wrote a book; and the enormously fat, narcoleptic, eminently colorful attorney Henry Kowalsky, who bribed journalists, editors, and a staffer on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Still, time was running out for King Leopold’s fictions. In 1905, he created another sham commission to investigate atrocities in the Congo. Much to his horror, it actually did so, and produced an accurate and damning report. Leopold bought himself a little time by releasing an inaccurate ‘summary’ in English the day before the full, long, French-language report came out. The summary was written by another legal fiction, the West African Missionary Association, which was later shown to be nothing more than an empty office guarded by a single night watchman.

International condemnation ultimately forced Leopold to leave the Congo business. Even kings are subject to international pressure, it seems. He sold control of the Congo Free State to the Belgian government in 1908. The Belgians still ran the Congo cruelly, but by no means as horrifically as Leopold had. In a final act of cover-up, Leopold had the entire archives of the Congo Free State, both in Brussels and in Africa, burned. He’s quoted as saying, “I will give them my Congo, but they have no right to know what I did there.”

Image credit: The Wellcome trust. Released under a CC BY 4.0 license.

King Leopold’s information operations are an amazing template for a villainous organization in an RPG campaign, particularly in a more corporate-focused setting like Blue Planet or Shadowrun. You can break Leopold’s operations into six categories: fabricating propaganda, hiding behind fictional organizations, starting false investigative commissions, restricting the flow of information, covertly lobbying governments, and bribing newspapers to run more flattering content. You can totally run an adventure around defeating some combination of these!

– Fabricating propaganda. This is the easy one. If it looks like propaganda, it probably is. PCs can follow the money trail on whoever is writing books/magazine articles/blog posts sympathetic to atrocities, and they’ll probably find the author is being paid off by your campaign’s Leopold-analogue.

– Hiding behind fictional organizations. PCs can determine if organizations involved in the plot actually have members (unlike the West African Missionary Association), if those members actually meet (unlike the International Africa Association), or if the members actually have any relevant expertise (unlike the Committee for Studies of the Upper Congo).

– Starting false investigative commissions. PCs can meet with the commission and examine their legal foundation. Do they have any legal authority? Are the commissioners interested in doing their jobs? Has the commission ever actually met?

– Restricting the flow of information. PCs can establish covert channels to get information out of the black box. They might establish a dead drop at a neutral port just outside your Congo-analogue or find a sympathetic power that’s willing to hide smuggled information in their un-inspectable consular mailbags.

– Covertly lobbying governments. This one’s trickier! The PCs will probably have to cultivate contacts of their own who can report whether any powerful people have suddenly picked up a new pet cause (like Chester A. Arthur and Nelson Aldrich did) or are unexplainably changing direction (like the British Foreign Office did, when they slow-rolled their report at the urging of Constantine Phipps). The PCs will probably then have to monitor the powerful people to see who they’re hanging out with now that they weren’t before. A new figure in the powerful person’s life may be the secret lobbyist.

– Bribing newspapers to run more flattering content. This one’s tricker still! Bribes are hard to ferret out, since they’re usually done in cash and there are no receipts. The key is seeing which reporters and editors have suddenly started changing their tune or started living above their means. That’s still not proof, though; PCs may have to shadow a suspicious journalist for a month or two to catch them in the act of taking a bribe.

–

Source: King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild (1998).