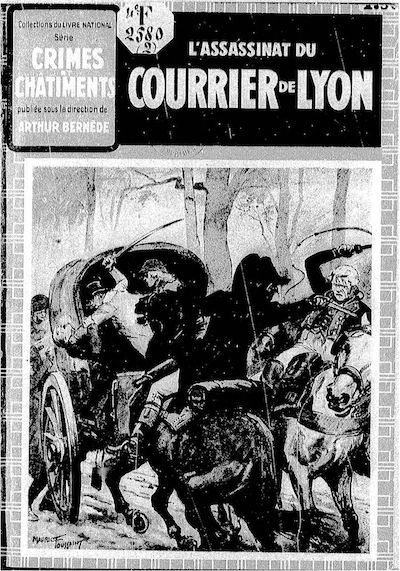

The case of the Lyon mail robbery of 1796 used to be a huge pop culture phenomenon. You know how everyone knows who D. B. Cooper or Charles Manson are, even without the endless TV episodes and books and spin-offs? In the 19th century, the Lyon mail robbery had that level of cultural penetration. It’s got a stolen treasure, two grisly murders, and a man falsely executed (maybe). What’s great about the case from a gaming perspective, though, is the actual involvement of the falsely-executed man is still unclear. If you fictionalize the case for your campaign and set your PCs to solving it, this guy – the iconic character at the heart of the tragedy – makes it super easy to plug the case into whatever genre elements are important to your fictional campaign setting. Let’s dive right in!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

The French First Republic had a reliable postal system. Mail coaches ran 24 hours a day, changing horses periodically at inns. The coaches carried government orders and shipments, the parcels and letters of the wealthy, and sometimes passengers. If you had the money, it was a fast way to travel, albeit uncomfortable. On May 26th, 1796, a mail coach left Paris for Lyon carrying boxes of coin and paper money worth seven million francs. The coach carried two drivers and only one passenger: a wine merchant. The merchant had no luggage (which was normal), but did have a cavalry saber (which wasn’t).

The coach stopped at Montgeron, outside Paris, to change horses. Four strangers had been dining at the inn there. One was distinctive: a tall, strapping blonde man who paid for lunch for all four. The coach made its next stop, but not the one after that. A search the next morning turned up the body of one of the drivers in a field. Someone had held his arms while someone else slashed at him. The other driver had clearly tried to run, as his body was found farther up the road with a missing hand. A single spur was also found nearby – presumably one of the attackers lost it in the fracas. The wine merchant was nowhere to be found.

A police investigation revealed that the same four strangers had been spotted at the stop after Montgeron. The landlady of the inn there had stitched a loose spur back onto the boot of one of the riders. And the police got a report that one Etienne Couriol had been spotted in Paris leading four horses that matched the descriptions of the strangers’ mounts. The horses were in a lather, as if they’d been riding hard. Couriol was tracked to the house of a known fence, Pierre-Thomas Richard. The police arrested Richard, his servant, and one Charles Guénot, a guest in Richard’s house. The cops soon concluded Guénot was not part of the murder-robbery and released him. They told him to come to the courthouse next week to pick up his identification papers, which they’d seized.

Couriol, the man with the horses, was already gone from Richard’s place by the time the police showed up. They caught up with him a week later in a town sixty miles from Paris and arrested him. They also arrested Couriol’s lover, Madelaine Breban, who’d fled with him. The two had over a million francs on them.

This is where we introduce the central character in this mystery, at least as far as 19th century pop culture was concerned: Joseph Lesurques. Lesurques was a retired sergeant from the French Army. He’d made a few lucky investments and was a wealthy man. Despite his wealthy station, he was a friend of Richard the fence and Richard’s guest Guénot. As Guénot was headed to the courthouse to pick up his identification papers, he bumped into Lesurques. Lesurques offered to come with him for moral support. When the two strolled into the courthouse, they encountered two barmaids from the inn in Montgeron, who were there to give their testimony. The barmaids flagged down a guard and pointed out Lesurques – who was tall, strapping, and blonde – as the lunch-buying stranger. Lesqurques was arrested and Guénot was re-arrested for clearly being more connected to the murder-robbery than the police initially realized.

At the trial, Lesurques felt he had a good shot at being acquited. Yes, Couriol’s lover, Breban, had turned state’s evidence and fingered him. And yes, another witness connected the fallen spur to Lesurques. But Lesurques was able to call sixteen witnesses to attest to his whereabouts. Unfortunately, one of the witnesses ruined Lesurques’ whole case. He was a jeweler who produced a sales report showing Lesurques had visited his shop on the day in question. But the report was a clumsy forgery: someone had written the desired date atop the real date, an ‘8’ written over a ‘9’. Even the inks were obviously different. If the jeweler witness was fake, why not the rest? The judge instructed the jury to view Lesurques’ witnesses with extreme suspicion. Lesurques was convicted.

In the days before his execution, Couriol (the man with the horses) admitted his guilt – but declared that Lesurques was entirely innocent! He also named four additional men who were part of the murder-robbery. Couriol’s lover, Breban, also changed her tune. She said she had dined with Lesurques at the home of Richard the fence on the night of the crime. She’d denied this at the trial. She also confirmed that one of the four men Couriol was now blaming did look a lot like Lesurques. He was tall, strapping, and wore a blonde wig. The court wasn’t interested in this new testimony, concluding that the wealthy Lesurques had probably paid for it, just as he’d paid for the jeweler’s testimony at trial. The executions went ahead as scheduled. Lesurques went to his death proclaiming his innocence.

Let’s keep track of the numbers, because it will matter later. With four strangers at the inn in Montgeron, plus the wine merchant who was presumably a plant, that’s five people involved in the murder-robbery. The court executed four for the crime: tall, blonde Lesurques; Couriol, the man with the horses; Guénot, the friend of Lesurques and the fence Richard; and Richard’s servant. Richard himself was sentenced to twenty-four years of penal servitude. With five robbers and four executed, that’s one robber left unaccounted for.

The first of those named by Couriol (the man with the horses) was arrested in the spring of 1797. He was the fake wine merchant. Before he was executed, he claimed the robbers knew which coach to hit because they had a contact inside the postal system. The second man named by Couriol managed to escape before trial, but was recaptured and executed. The third fled Paris for Lyon, then Italy, then Spain. He was arrested in Spain for a different crime, then extradited to France, identified by forty-eight witnesses, and convicted. He then made a private statement to a priest claiming that Lesurques was innocent. At the convict’s request, the statement was released six months after his execution. The reason for the requested delay has never been satisfactorily explained.

But it’s with the fourth man – Jean-Guillaume Dubosq – that things get really interesting. Dubosq was the one who looked just like Lesurques and wore a blonde wig. In his accusation, Couriol identified Dubosq as one of the ringleaders, and the first one to attack the coach drivers. He was usually a cat burglar, not a highwayman. And he didn’t have to be arrested. Dubosq was already in prison for an unrelated crime! His lover was in the same institution, one Claudine Barrière. They escaped that prison, but Dubosq broke his leg in a fall in the process. They were picked up by the night patrol. The prison doctor moved Dubosq to a cell with a fireplace and overlooking a garden. To aid his recuperation, Barrière was permitted to stay in his cell. After six months of convalescence – an unusually long recovery – Dubosq and Barrière escaped again! They’d taken bricks out of the fireplace and fled through the hole they made.

Two years later, the police recaptured Dubosq and Barrière. In the couple’s house, the police found disguises, burglary tools, and eight forged letters of identification. Now that Dubosq was in hand and well enough to travel, he could finally be tried for the mail murder-robbery. The trial was done on thin evidence. Six officers said they’d never confused Dubosq and Lesurques. The barmaids denied that Dubosq was the tall, strapping blonde who’d paid for the meal. All nine witnesses who’d identified Lesurques denied that Dubosq was the man they’d seen. Only Richard, the fence, who was summoned from prison, identified Dubosq as one of the robbers. (As an aside, on his way back to prison, Richard escaped and was never recaptured.) Statements from Couriol (the man with the horses) and one of the men he’d fingered both placed Dubosq at the crime. Of course, both of these men were long since executed; the statements were read from earlier records. In short, the criminals all said the tall, blonde stranger was Dubosq. The civilian witnesses all said he was Lesurques. Dubosq didn’t help his case much by offering unending satirical commentary on the court proceedings. The jury ruled that Dubosq had not been present at the murder-robbery, but had abetted it. Dubosq was executed. His lover, Barrière, received ten years in prison.

So now we’ve got eight men executed for a five-man crime. Admittedly, not all were convicted of murder. A high court issued a statement reminding the public that the convictions of Lesurques and Dubosq were reconcilable. But the whole thing was fishy. The Ministry of the Interior had to remove graffiti from Lesurque’s tomb reading “Down with the unjust sentence!” and “The greatest of the degradations of the human species”.

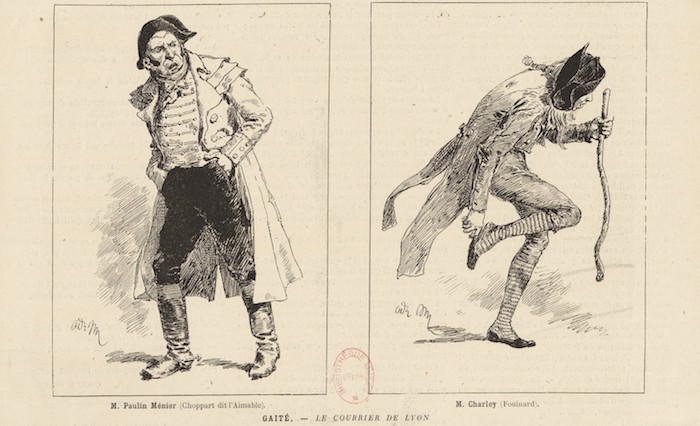

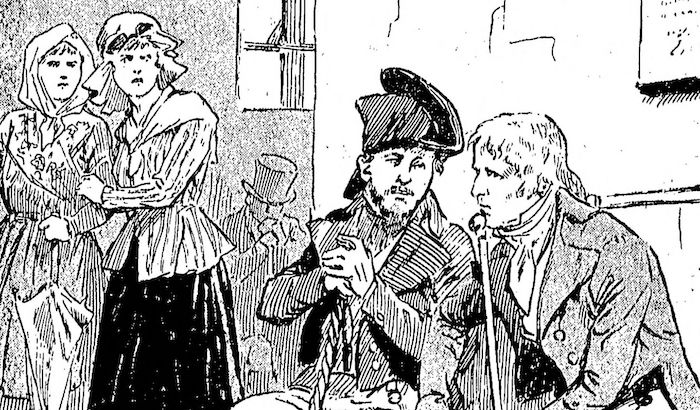

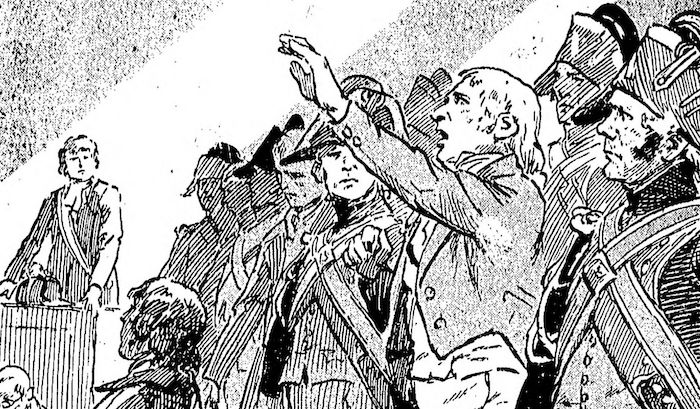

The pop culture of the era seized on the idea that Lesurques was innocent. A number of novels and plays were published, most of which had only a loose connection to the facts of the case. A play by Charles Reade became a huge hit in Victorian Britain. It starred the same famous actor as both Lesurques and Dubosq. The case had a long tail, too. A British film about it came out in 1968, and there’s a reference to the case in an Astérix comic from 1963.

So was Lesurques actually involved in the robbery of the Lyon mail and the two murders that came with it? If he wasn’t, he sure was keeping odd company. You wouldn’t expect a wealthy man to maintain friendships with the fence Richard and with Breban, the lover of the robber-murderer Couriol. And all those witnesses sure seemed certain that Lesurques, not Dubosq, was the meal-buying stranger at the inn. But all this evidence is circumstantial. That doesn’t disqualify it; it’s still evidence. But weighed against two claims by condemned men with nothing left to lose… It’s hard to say. There’s also the fact that Lesurques’ considerable property was seized by the state after his execution. The judge who pressured the jury to convict him had a motivation to see him dead.

If Lesurques was involved in the crime, what was his role? Certainly, he could have been the tall, blonde murderer with the loose spur. But he also could have been a financier or mastermind. He was certainly well-positioned to have a source inside the postal system as was alleged. This could also explain why he’d go to the courthouse with his friend Guénot to help him pick up his identification papers. If Lesurques wasn’t present at the actual murder-robbery, he wouldn’t fear identification at the courthouse. His resemblance to Dubosq would have been exactly what it seemed: a coincidence.

At your table, the ambiguity over the role of Lesurques is the key to making the case work in your fictional campaign setting. When you make the case your own, you can have your Lesurques-analogue play a role that fits your setting’s ‘premise’ or genre elements. Playing a Lovecraftian game? Lesurques is a cultist who needs the seven million francs to do something terrible. Playing a game about psionics? Lesurques is a mutant on hand to defeat the coach’s mental defenses. Space opera? Lesurques loaned out the fancy ship that can overtake the speedy messenger ship in exchange for a cut of the profit. What’s great about Lesurques is that he’s integral to the whole story – without him, would your Couriol-analogue turn in four more conspirators? – yet he can genuinely be whatever you want him to be. It won’t affect the rest of the case.

You don’t have to be playing a detective campaign for an adventure based on the Lyon mail robbery to work well. There’s still a missing treasure out there: Couriol and Breban had only had a fifth of it on them when they were arrested. If the PCs can beat the cops to catching the rest of the robbers and murderers, maybe they can seize the rest of the treasure! And again, Lesurques’ ambiguity widens the possibilities. In a political game, Lesurques could be a rival the PCs want to see brought down. In an idealistic game, Lesurques might be an innocent man the PCs need to set free. In any game, if a PC is mixed up with some shady characters, that PC could fall into the role of Lesurques when she’s arrested for associating with a criminal who did a job with someone who looks just like her!

Two last notes. First, make sure your version of the coach is carrying genre-appropriate cargo. Seven million francs in a stagecoach is cool, but if you’re doing an underwater game, make it a submarine carrying life-saving medicines. In a mech game, have it be a cargo ship full of mechs. And second, this story has a lot of prison escapes. Make sure that in your adventure based on this story, the PCs at some point have to track an escaped fugitive or escape from prison themselves.

Want more content from this (very early) era of French policing? This post is a follow-up to last week’s post about another remarkable case!

–

Source: The First Detective: The Life and Revolutionary Times of Vidocq by James Morton (2004)