Blanche of Castille was Queen of France from 1223 to 1252. She was a juggernaut – one of the most powerful people on the continent. She led spy rings, commanded armies, and helped turn France into the pre-eminent power in Europe. The story of how she negotiated a marriage for her son, King Louis IX (the future St. Louis), is a remarkable one. It has a lot of lead-up and context, but it’s totally worth it. And those negotiations make a template for a really interesting RPG adventure!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

In the 1200s, in what is today the south of France, the Count of Toulouse and the Count of Provence were rivals. Among other things, they disagreed over who should control the seaport of Marseille. Provence was the weaker of the two counties. It was known for its sunny vineyards and its troubadours. While Provence is today part of France, at the time the county was technically part of the Holy Roman Empire. In practice, though, the emperor was doing his own thing in Sicily, and Provence was effectively independent and had close ties with Aragon, in modern Spain. Provence’s rival, Toulouse had more territory and more soldiers, but fewer friends. The counts of Toulouse were theoretically vassals of the King of France. In practice, they thumbed their nose at the king and were, again, effectively independent.

The counts of Toulouse had long tolerated a heretical religious movement called Catharism. (I know, I know, I never stop writing about Cathars, but they’re just so cool and this post isn’t about them anyway, I promise!) This earned them the ire of the pope, who tolerated no heresy in his part of Christendom. That disagreement boiled over when a papal legate to Toulouse was murdered under mysterious circumstances. The pope blamed Count Raymond VI of Toulouse, excommunicated him, and declared a crusade against him and the Cathars in his county. In particular, the pope declared it right and proper that any Catholic lord who seized part of the County of Toulouse as part of the crusade should get to keep it. The King of France saw this as a marvelous opportunity to gain territory, show strength, and display piety. He sent an army to invade the County of Toulouse. The so-called ‘Albigensian Crusade’ lasted from 1209 to 1229. Hundreds of thousands of Cathars were murdered.

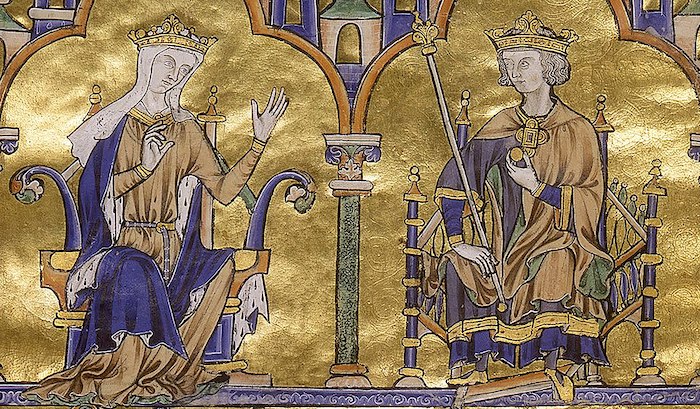

But events elsewhere were brewing to shift France’s attention. King Louis VIII of France died in 1226. His son, Louis IX, was twelve. Instead of leaving France to a regent until Louis IX came of age, Louis VIII left full authority to his own wife and queen, Blanche of Castille, who would rule in her own right, not acting on behalf of her young son. Queen Blanche knew some of the French barons would see a woman on the throne as an opportunity to rebel, and that they would probably be backed by England, which would seize any pretext to weaken the throne of France. It bears noting that Blanche’s husband, the late Louis VIII, actually invaded England himself while still only a prince, was acclaimed king by rebellious English barons during the First Barons’ War, and at his high-water mark ruled half of England. And it was actually Blanche’s bloodline, not Louis’, that made the rebellious English barons pick Louis as their pretender. All of which is to say that there was plenty of bad blood between England and France (and with Blanche in particular), and England would surely help a rebellion by French barons.

So back to the south! The Albigensian Crusade was good news for Provence. Its rival Toulouse was too busy getting the snot beaten out of it to conspire to gain Marseille. Plus, every innocent Cathar burned alive was a pair of hands that couldn’t feed the army of Toulouse or be conscripted into its ranks. But with Queen Blanche’s attention pulled elsewhere, Provence’s reprieve came to an end. In January of 1229, Blanche led her army against one of her rebellious barons. In the spring of that same year, she agreed to a peace treaty with Count Raymond VII of Toulouse (his dad, Raymond VI, died seven years earlier). The treaty was harsh. Raymond VII agreed that the land he’d lost to France in the crusade would remain French, that France would tear down his walls and castles, that he’d let the Inquisition root out any remnants of Catharism, that he’d pay reparations to the Church, and that he’d go on crusade. He’d also wed his only child (a daughter) to one of Blanche’s lesser sons – thereby making it likely that the County of Toulouse would eventually pass into the hands of Blanche’s family. In exchange, Raymond VII got to remain Count of Toulouse – though now as a real vassal of France. No more of this ‘effectively independent’ stuff.

The peace treaty scared the Count of Provence. Toulouse was weaker now, sure, but it was no longer distracted. And Raymond VII now had a friend and relative in Queen Blanche. Once she dealt with her own rebellious barons and the English invasion (it wound up taking five years), maybe Blanche would help Raymond against Provence. The Count of Provence, Berenguer IV, needed new friends and relatives to defend against this possibility. Berenguer’s seneschal, a cunning man named Romeo de Villeneuve, decided the best way to make friends would be to find a husband for Berenguer’s oldest daughter. And who could be a more useful friend and relative than Queen Blanche herself? King Louis IX was still unmarried. Might Provence arrange a union and thereby turn the tables on Toulouse?

Provence’s first line of attack was the troubadours. The county was famous for them. The counts of Provence had long patronized the bardic arts. Berenguer’s own grandfather was called ‘Alfonso the Troubadour’. These traveling performers were welcome at courts across France, spreading news and singing songs. Given the special relationship between troubadours and Count Berenguer, the performers didn’t need much encouragement to add to their repertoires songs about how Berenguer had no sons and four daughters, each lovelier and more pious than the next. O their breeding was impeccable. O their manners were perfect. O the grace and delicacy of the court in which they were raised would make each of them a wife without peer for any young nobleman – the more highly-placed the better.

Image credit: Odejea & Ninanta. Released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

Queen Blanche was no dummy. Her prodigious network of spies told her exactly what Berenguer and Romeo were up to. It also told her that Count Raymond of Toulouse was chafing under the yoke of his new peace treaty. He was eyeing those territories he’d lost to France in the crusade and wondering what he could get away with. To keep Toulouse subdued and loyal would take an army Blanche couldn’t spare. But if she could prop up a rival to Toulouse, a counterweight to Raymond’s ambitions, maybe she wouldn’t have to send an army. Maybe politics would be enough. The poetical overtures coming out of Provence found a receptive audience in Blanche. She dispatched an envoy, Giles de Flagy, to check up on events in Toulouse and Provence. Giles found Count Raymond of Toulouse unhappy. He didn’t like the restrictions the church had placed on him, didn’t like losing his walls and castles, didn’t like the money he had to cough up as reparations, and really didn’t like this business about his lands someday passing into Blanche’s family. Giles also made a stop in Provence (unbeknownst to Count Raymond of Toulouse), where Romeo and Count Berenguer made the visit an endless party – and wouldn’t shut up about the worthiness and piety of Berenguer’s oldest daughter, Marguerite, then twelve years old. She’s hot, she’s pious, she’s hot for piety. A perfect match for the nineteen-year-old zealot Louis IX.

Queen Blanche agreed to wed her son, the king, to Marguerite of Provence, but at a considerable price. If the daughter of a mere count was to wed the King of France, the count had better pay for it. To secure the marriage, Provence was to pay a dowry of ten thousand marks of silver. Count Berenguer didn’t have anywhere near that much. His network sprang into action. His wife’s brother, the Bishop of Valence, convinced the Archbishop of Aix to front Provence two thousand marks in exchange for an unspecified future favor. The remaining eight thousand would be trickier. But Berenguer’s seneschal, Romeo de Villeneuve, had some financial chicanery at the ready. Romeo had long succeeded in borrowing money for Provence by pledging some of Berenguer’s castles as collateral. If you loaned Berenguer money and he started missing payments, you could claim the castles he’d pledged to you. Romeo and Berenguer pulled the same trick with Blanche, pledging several castles as collateral to back up a promise to pay the remaining eight thousand marks on the installment plan (or Blanche could just take the castles). Blanche agreed to the loan, and the marriage went ahead in 1234.

Though Romeo never seemed to get any pushback from his creditors, later observers might take issue with some details of the loans. First, Romeo always pledged the same castles. So if Count Berenguer ever decided to welch on all his debts, his creditors would have to split the castles between them, which was hardly the ironclad collateral they were promised. Second, even if a creditor were to attempt to take possession of a castle, how would they do it if Berenguer were to put up a fight? Berenguer had knights and siege engines and peasant levies, while moneylenders had pieces of paper. That was the whole point of the Medieval warrior aristocracy – the lords were in charge because they had all the swords, and if you said otherwise they’d stab you. So these loans were dangerous investments for the moneylenders at best. Finally – and this is silly, but I have to mention it – there is the matter of the dragon. One of Berenguer’s castles that Romeo routinely mortgaged was at Tarascon, famously the home of the tarasque, a dragon tamed by St. Martha and the namesake of D&D’s Godzilla-analogue. The tarasque was long-dead, so popular belief went, but at your table…

In the vein of preparing situations, not plots, this whole marriage negotiation is fabulous inspiration for a situation in your fictional RPG setting, once you file the serial numbers off. And for God’s sake, age up Marguerite. At your table, I propose you encourage your PCs to work against this marriage. Blanche of Castille is easily the coolest person in this story – and a super cool person in general – but she makes a better antagonist than a patron. Queen Blanche is a juggernaut, an absolute powerhouse. That’s what makes her so cool! But working on behalf of a powerhouse can be dull. It’s often more fun to fight for the underdog. If nothing else, there’s more conflict when you’re with the underdog, and conflict lies at the heart of story.

The underdog here is, weirdly, Count Raymond VII of Toulouse. He’s getting the snot beaten out of him because his dad wouldn’t play along with the Church’s desire to murder people of different faiths. He’s got a terrible treaty forced down his throat. Everything he’s fought for may pass in a generation or two to the people who knocked him down. And when he briefly gained a single ally, his neighbor immediately started plotting to steal that ally from him. In real life, Raymond VII was a bit of a shit, but in your fictional setting, he make a great empathizable underdog NPC.

So how do you find where in your setting to put an adventure based on this story? First, find your juggernaut, the nation led by your Blanche of Castille. Ideally, it’d be some sort of bad guy power, like Nilfgaard in The Witcher or Neraka in Dragonlance, but it doesn’t have to be. Then pick your favorite among the various states the bad guys are crushing. Any of the underdog state’s neighbors can play the role of Provence – especially one that makes a cool setting for adventure, since most of the action will happen there.

Your fictional counterpart of Count Raymond of Toulouse asks (or hires) the PCs to prevent the marriage of your Blanche-analogue’s son to your Provence-analogue’s favorite daughter. The troubadours are already out; there’s no stopping word from reaching Queen Blanche. But when your analogue of Giles de Flagy shows up in Provence, the PCs can insert themselves into the festivities and try to spoil them. Make Marguerite angry so Giles is less impressed by her. Figure out who Blanche’s spies at court are and whisper rumors to them about how Marguerite (gasp!) might not be perfectly pious. The PCs probably can’t scuttle the plan at this point – the match is too sensible for all involved – but they can make Blanche less excited about it. If they succeed at this, she’ll raise the size of the demanded dowry. And that’s where the real fun begins.

Gathering the money for the dowry is the point at which this marriage negotiation can fall apart, and it’s also the most complicated step, the part where the PCs have the greatest latitude to get creative and make meaningful decisions. If they can sour the Bishop of Valence on the union (“You and your relatives are vassals of the Holy Roman Emperor. Why are you strengthening your family’s relationship with his rival, the Queen of France?”), maybe the bishop won’t intercede with the Archbishop of Aix. If the party can spook some of Berenguer’s outstanding creditors, maybe they’ll demand repayment (or a castle) and mire him in a messy standoff that makes the Count’s promises to Blanche look less credible. If the PCs can stir up the old dragon under Tarascon, maybe Blanche won’t want that castle as collateral. Maybe the PCs could assassinate Romeo, heist what money Berenguer has on hand, waylay the messengers he sends to assure Blanche that everything is going smoothly, or get one of Berenguer’s vassals to rebel, thereby occupying attention that should be spent gathering resources. Plus, once Berenguer figures out what the party is doing, he’ll send teams of knights to kill them, which is always fun.

The PCs don’t have to succeed at every clever scheme they develop. The bigger the dowry Blanche demands, the fewer of the PCs’ schemes need to succeed. This business with the dowry is messy. There are a hundred ways the party can approach it. And that’s what makes it so great at the gaming table.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on Facebook, Twitter, or Mastodon to increase visibility for the Molten Sulfur Blog!

Source: Four Queens: The Provençal Sisters Who Ruled Europeby Nacy Goldstone (2008)