North Rona (or just Rona) is a tiny island in the icy waters far off northern Scotland. Its geography and animal life would make it a cool adventure site on their own, but its real claim to fame is that in 1685, a plague of rats wiped out all human life on the island, with the outside world none the wiser. I’m a sucker for stories where the heroes arrive somewhere that should have people but find no one home, and North Rona Island presents a really gameable take on that trope!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Scottish writer and amazing-name-haver Martin Martin heard a bunch of stories about life on Rona from before the rat apocalypse. He got these stories from natives of the much larger isle of Lewis (45 miles from Rona) who’d visited Rona, and from Rona’s owner, the minister Daniel Morison. They made it into his 1703 A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland, which as far as I’m aware is our best source for what was happening on Rona before people were wiped out there.

Rona was home to five families. They kept cows, sheep, barley, and oats. Each family had a dwelling and three outbuildings, and were very conscious of the boundary lines between each family’s properties. They preferred to marry other Ronans, but if no spouse could be found, they’d send for one on Lewis, presumably attracting only the poorest and most desperate Lewisians. Only a few Ronans ever left their island (usually just to Lewis), and found everything about the outside world shocking. Lewis’ only town, Stonrnoway (currently population 5,000), was a vast metropole teeming with an unimaginable number of people. One Ronan in Stornoway heard a horse neigh and asked if the animal laughed at him. Another saw a colt running towards him and was so afraid he jumped into a nettle-bush. One Ronan had the opportunity to visit a manor house near Inverness; when he heard people walking on the second story above his head, he fell to the ground to save himself from the house’s certain collapse.

So isolated from the rest of the world, culture on Rona developed some odd quirks. The Christianity they practiced didn’t much extend beyond the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and devotion to St. Ronan, who supposedly settled the island. In the chapel to St. Ronan they kept ten stones to which they ascribed magical properties. Many claimed to have second sight, which allowed them to prophesy the arrival of travelers. They had no concept of money or gold. This makes it all the more surprising to me that Martin’s source, the minister, “owned” North Rona, since the Ronans paid him no rents and so in what sense does the minister own the island? The minister also described the strange way he was greeted on arriving at the island: someone ritually walked around him clockwise, everyone addressed him as “traveler,” and he was given a special gift: the Ronans slaughtered sheep on the spot, took the wet skins, filled them with barley, and gave the bundles to him. The boatmen who brought the minister to Rona were familiar to the Ronans and thus not given their special gift for outsiders.

Image credit: David Hoult. Released under a CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED license.

This odd, isolated culture came to an end in 1685 when a boat visiting the island brought the black rat (Rattus rattus) to Rona. Most people take measures to keep pests out of their granaries: they build them on stilts or keep them sealed. Rona had no pests that ate grain, so the Ronans took no such precautions. The rats got into the barley stores and ate everything. The rats might also have brought plague. The same year, a gang of sailors (pirates really) robbed North Rona of much of its livestock. Between the loss of the barley and the livestock, the Ronans all starved to death. Then the rats also starved to death, having grown to such numbers that they ate all the seaweed along the shoreline. The steward of the St. Kilda islands (130 miles away) was forced to Rona by a storm and found no one alive, just the remains of a woman with a child at her breast.

Years later, the minister who owned the island sent some people to resettle North Rona—and this time made sure to include a provision that they owed him rent. But the boat he sent them a year later to deliver much-needed supplies and collect the rent was lost at sea, and these people too starved to death.

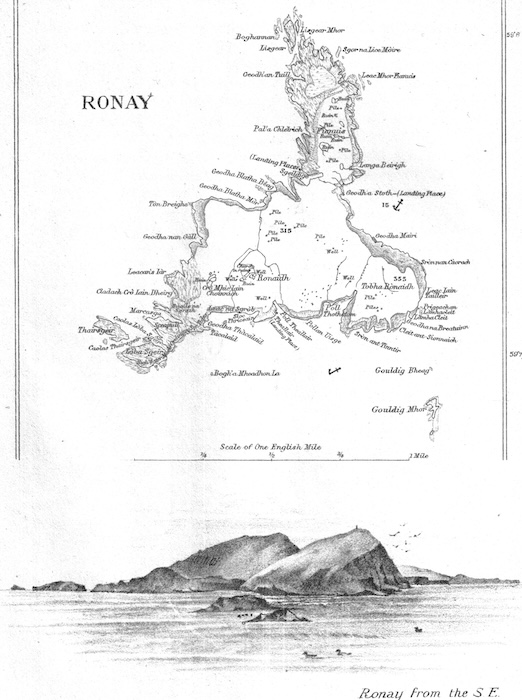

Today, North Rona is a nature reserve. It’s equal distance (45 miles) from both the island of Lewis and the northernmost tip of Scotland. It’s called North Rona to distinguish it from an unrelated island 100 miles away in the Scottish Hebrides called Rona or South Rona. North Rona is a weird shape, but it’s overall about one mile by one mile in size. It’s surrounded on all sides by rocky cliffs of varying steepness. The sward is dominated by chickweed, a weed that thrives in waste ground, like the large swaths of the island where the settlers harvested the turf for fuel and building material, or denuded the soil in the fields. There is still grass around the edges of the island and it’s luxurious, fertilized by the countless seabirds that now nest here: puffins, storm petrels, guillemots, razorbills, fulmars, and Manx shearwaters with their unearthly shrieks.

In the 60s, Rona was the largest breeding ground of gray seals in the world, birthplace of one-seventh of the global population. Since then, other breeding colonies in the North Atlantic have rebounded, but the seals still love Rona. To get on land, the seals approach the least-steep rocky cliffs, grip with their front flippers, and haul themselves up the slope. The bulls arrive first in late August or early September, staking out territory in the interior of the island. They’re big and fat; they won’t return to the sea to feed until they’re rail-thin. The cows arrive pregnant, 2-5 days before they’re due to give birth. They choose a territory to calve in, wean their single pups, mate with the bull of their territory, and return to the sea, usually all in two to three weeks. Once the bulls leave, they leave for good, but the cows will often stay in the area to hang out on the rocks, even after their pups are weaned. As breeding season lasts until November, the same territory is not controlled by the same bull all season. There’s a reserve pool of waiting bulls, some 500 strong, just off the breeding grounds, waiting for someone to depart his territory so one of them can step in. Every so often, one of these sexually-frustrated bachelors will try to push inland to fight a settled bull off his territory. Over the whole scene there are gulls, gorging on the seal placentas scattered everywhere.

Before the industry collapsed, sealers targeted North Rona’s seals for food, leather, and fat for lamp oil. Cheap rubber and kerosene came on the market just in time to save the seals. Seal leather and seal fat were suddenly worthless, and seal meat was good enough for sustainable local consumption, but not tasty enough to export. The birds too used to be targeted; people would travel to the island to gather eggs and fledgelings for food.

The cliffs of North Rona are a super cool place for a fight. Coming ashore, the swells carry the boat forward and back so you have to time your leap such that it carries you as far up the cliff as you can, hopefully onto a place where you can stand and pick your way up. The cliffs are intercut with gullies ten feet deep and a few yards wide. The gullies are full of boulders, some “merely” too big to be lifted, others as much as ten feet in diameter. The walls of the gullies are scarred from when storm waves are so great that they lift up these boulders and roll them around. Not only is this super cool combat terrain, you can have the party’s landing be opposed, so the PCs have to make rolls to make the leap from the boat onto the shore mid-fight. If this is in the middle of a violent storm, you might have waves rush into the gullies, pick everyone up, and bash them against the walls—and maybe even drop boulders on top of them.

If you’re thinking of using the disappearance of people from North Rona as an adventure hook, I’d introduce the island early. Use the island (or a fictional island based on it) as the jumping-off point for some other adventure so the PCs see all this weird folk-horror setup with the odd people and their odd religion. Then when the party returns from this other adventure, everyone on Rona has vanished. The rats have eaten everything, down to the bones of the dead and the seaweed on the shore. No human bodies remain. As the PCs track down transient sealers or bird-harvesters (or selkies or bird spirits) for what they know, the party might have to fight off Ronan ghosts—or five hundred sexually-frustrated bachelor seals. This line of inquiry leads the party to the pirates, who turn out to be more desperate and unscrupulous fishermen than high-seas buccaneers.

Then you have to decide how you want to handle the reveal: was the rat apocalypse on North Rona natural? Was it just some unfortunate accident that rats happened to jump off a ship at around the same time pirates took all the livestock, perhaps inadvertently delivering the rats in the process? Did someone make sure the rats got off the boat as part of an occult war among supernatural forces or with the campaign’s villain? Or was this a scheme by the island’s owner who wanted to replace a bunch of deadbeats who didn’t understand currency with new settlers who’d pay him rent?

You don’t have to decide the answer until the PCs are getting close to the end! That gives you the opportunity to let your players tip their hands as to what kind of answer would be most satisfying. Then go with that! The answer is definitely a rat apocalypse no matter what, but who was behind the rat apocalypse is whatever your players let slip they would most enjoy.

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Check out my book Making History: Three One-Session RPGs! It’s three awesome historical one-shots with pregenerated characters and a very simple rules system designed specifically for that story. Norse Ivory is a game about heritage and faith in the Viking Age. A Killing in Cahokia is a murder mystery in the Native American temple-city of Cahokia. And Darken Ship is a horror-adventure starring junior sailors on a U.S. Navy warship who wake up one morning to discover they’re alone on a ship that should carry three thousand.

Sources:

Description of the Western Islands of Scotland by Martin Martin (1703).

Natural History in the Highlands and Islands by F. Fraser Darling and J.M. Boyd (1969)

The management of offshore islands for nature conservation: the outer Outer Hebrides by Stewart Angus and David Maclennan in Journal of Conservation (2015)