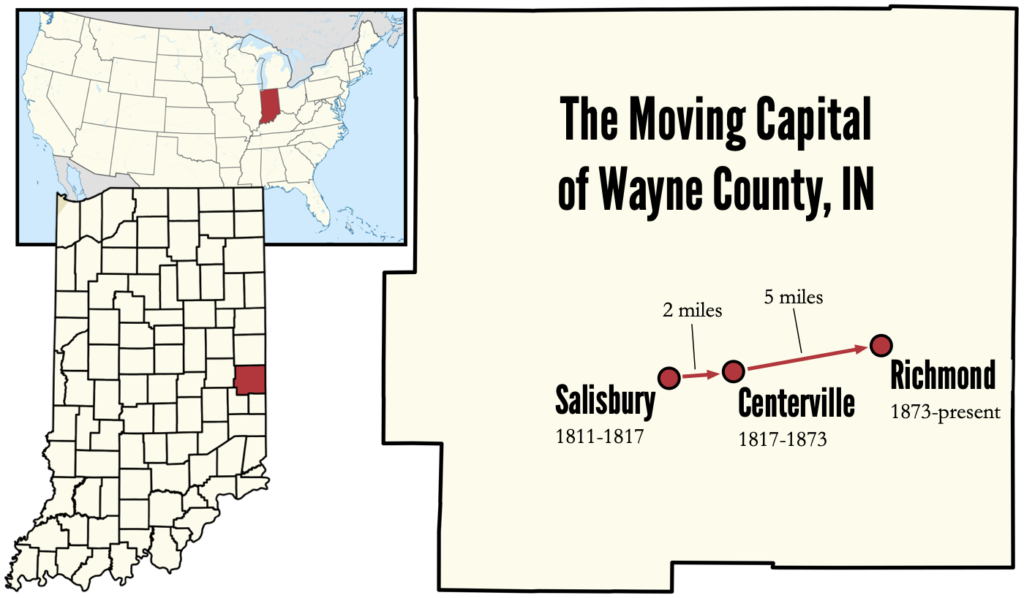

Between 1811 and 1873, Wayne County, Indiana had three different capitals and six different courthouses. Each time the county seat moved, it was incredibly contentious, involved lots of guns, and one time a cannon. The stakes were high – these events led to one town’s irrelevance and another’s outright dissolution. Yet the stakes were also trivial. In all these shifts, the county seat moved a total distance of seven miles. It’s one of the pettiest feuds I’ve ever encountered, and people cared about it passionately. It makes great inspiration for an RPG adventure.

I’m running a Kickstarter campaign right now for an early-access zine edition of Ballad Hunters, my RPG about magical folk ballads in 1813 England and Scotland. You should check it out!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Robert Nichols. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Robert, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

The choice of Wayne County’s capital (more properly, the ‘county seat’) was contentious from the beginning. The Northwest Indian War of 1786-1795 ended with the United States conquering and holding most of the relevant territory. It was a nasty war concluded by the large-scale burning of Indian villages. The new territorial administration of this freshly-conquered and forcibly-depopulated land established Wayne County in 1811 and set the county seat at a tiny white settlement named Salisbury. Much of the settler population preferred a different location, one two miles east of Salisbury, at a place that did not yet have a village. But the federal government had not yet made that plot available for sale (though it was expected to do so very soon), and the territorial judges decreed that a county seat couldn’t be seated provisionally on land that couldn’t yet be purchased. Clear as mud?

To the handful of families building houses and farms in Salisbury, being selected as the county seat was a great coup. A county seat would mean a courthouse, a jail, and a handful of part-time jobs staffing them. Soon it would mean a few lawyers, and those lawyers would need services like stables, smithies, and taverns, and the people working in those establishments would themselves need services, and so forth. Your tiny settlement being selected as the county seat meant that it was going to grow – maybe even prosper! – and you’d be on the ground floor to profit from it.

Not everyone was thrilled about the choice of county seat. Salisbury was a little farther west than some people wanted, and folks in the eastern part of the county would have to travel a little farther to reach it. An informal vote revealed a majority of the population preferred a more central location than Salisbury, but the judges’ decision held. The residents of Wayne County who didn’t like Salisbury immediately submitted a petition to the territorial legislature to impeach the judges whose decision they disliked, but the petition didn’t go anywhere. In 1812, Salisbury constructed its first courthouse: a two-story log cabin.

Image credit: Morrisson-Reeves Library, Richmond, Indiana

The fight over the county seat was just getting started. In 1814, the more-popular site was surveyed and named Centerville. In 1815, a bill that would make Centerville the new county seat died in the Indiana territorial House of Representatives. In April of 1816, Indiana was made a state, in June the new state drafted its constitution, in October the Wayne County commission set aside funds to build a permanent brick courthouse at Salisbury, and in December – only two months later! – the pro-Centerville faction in Wayne County succeeded in forcing a bill through the new state legislature moving the Wayne County seat to Centerville. Salisbury turned up its nose at the new law and continued building its courthouse.

The law making Centerville the new county seat had some strings attached. Centerville would have to construct a courthouse at its own expense – no state or county funds allowed. And the new courthouse would have to be at least as big as the one being constructed in Salisbury. Centerville had until August 1st, 1817 to meet these conditions or the county seat would revert to Salisbury. The financial condition was met easily enough when Centerville issued bonds (financial instruments) to fund construction. The other requirement proved trickier.

The state legislature required that the new Centerville courthouse be at least as big as the Salisbury courthouse that was just finishing construction. So Centerville sent some men to Salisbury to measure the courthouse. The residents of Salisbury all came out with their squirrel guns and formed a cordon around the building. The men from Centerville couldn’t get anywhere near it. They wound up having to hang back and count bricks: “It’s this many bricks wide, this many long, and this many tall. Those bricks look like they’re about so big, so that would make the courthouse… how big exactly?” It wasn’t an exact science, and they could have easily gotten it wrong. But they didn’t. The new courthouse was big enough, and Centerville met the requirements of the law.

But Salisbury wasn’t going down without a fight. First, the city fathers offered to reimburse the county for all funds spent on their now-obsolete courthouse if only the state would let them remain the county seat. (The state refused.) Then the three-person Wayne County Commission refused to move its business to Centerville. Two of the three commissioners were in the Salisbury faction, and they refused to even seat the third, who was in the Centerville faction. For the whole of 1818, all business from the Wayne County Commission was signed only by the two Salisbury commissioners. In violation of an 1818 confirmation by the state legislature and several court orders, they kept all county business in Salisbury. The judges of the court, of course, met where they pleased. Sometimes that was the courthouse in Salisbury, sometimes the one in Centerville.

In August of 1820, one of the two Salisbury commissioners was voted out, and now Centerville held a two-thirds majority on the county commission. The first order of business of the new commission was to adjourn their meeting in Salisbury and re-convene it two miles east in Centerville. The Salisbury commissioner refused to make the trip. He did not rejoin the board until November. The judges of the court now always chose to meet in Centerville. The lawyers moved to where the judges were, and the services moved with them.

Without court and county business to sustain it, Salisbury withered and died. In 1817, it had 35 houses, two stores, and two taverns. By the late 1830s, it had no residents whatsoever. Losing the battle for the courthouse was a lethal wound for the village. On the one hand, that shows just how serious this fight was. It was an existential battle for the very existence of Salisbury. On the other hand, towns aren’t people. It’s the actual people who live there that matter. And it’s not like any of them were badly hurt by this affair. All that happened was that they were now two miles farther away from the courthouse. Sure, there were no roads or bridges in the county, so that was two miles down twisting deer paths. But log cabins were easy to build, and with the forced displacement of the Shawnee and the Delaware, there was no shortage of land. If being in a county seat was that important to you, you could just move. And it looks like that’s what everybody in Salisbury did. On the third hand, for the Centerville faction – really? You’re going to go to this much trouble just to move the county seat two whole miles? This is just about the pettiest feud I’ve ever heard of.

But we’re a long way from done. Because while all this was going on, a third power was rising. The town of Richmond was surveyed in 1816 and had 200 residents by 1818. It was five miles east of Centerville, almost on the Ohio border. Richmond soon outgrew Centerville. And as early as the 1840s, the residents of Richmond started agitating that their town should be the county seat. By this point, it was easy to travel between the two towns. The new National Road, the first major highway in the United States, passed through them both as it wended from Maryland to Illinois. Richmond benefitted more from the road than Centerville seemed to – for what reasons I dare not even guess. Richmond became a manufacturing hub, then a road hub, then a rail hub. Centerville was a bit more embarrassing. The courthouse they threw up so quickly to meet the state requirements was poorly-built. It had to be replaced with a new one.

In 1872, Richmond made a grab for the county seat. Richmond’s representatives in the state legislature spent 1855 to 1869 passing laws that clarified how county seats could be moved in Indiana. Even against the backdrop of the Civil War, Richmond was plotting how it would grab its place in the sun and move the county seat five whole miles east. Under the new state law, if 55% of county voters signed a petition to move the county seat, it would happen. A petition circulated in 1872 got well more than that. If Richmond was willing to shoulder all the costs of the move, including new buildings, it would become the new county seat. Richmond was eager to get started.

Centerville prepared to fight. The city sued to stop the change, to no avail. Their lawsuit went all the way to the Indiana Supreme Court, but every court issued the same opinion: of course this change was legal, and none of it should have come as a surprise. By August of 1873, the new courthouse in Richmond was ready to receive all the old files stored in the Centerville courthouse. This is when Centerville got nasty.

To pick up the old files, Richmond sent eighteen express wagons. Fourteen of them squeezed into the walled square in front of the Centerville courthouse. Then the residents of Centerville slammed shut the gates to the walled square, trapping the wagons and wagon-drivers inside. The crowd outside waved pistols. A notorious deadbeat named Strickland announced he had sixty rounds of ammunition to use on the wagon-drivers if they tried to flee. Word reached Richmond, which responded with a restraining order against the crowd and an order for the wagon-drivers to stop the move. The wagon-drivers unloaded the boxes of files, put them back in the Centerville courthouse, and were escorted out of town by the armed mob. The files were eventually moved to Richmond, but were escorted by 300 Richmondites. Three wagons from Centerville helped with the move to forestall further trouble.

Richmond then opted to save some money on constructing a new jail by announcing it would tear down the jail in Centerville and use the recovered building materials. Work started in September of 1873. Vandals in Centerville ensured nothing got done. Under cover of darkness, they tore down the scaffolding Richmond-employed workers had erected around the jail. Richmond sent armed guards to protect the workers, which only escalated things.

On the night of October 28, there were seven guards in the Centerville jail, all employed by Richmond to guard the workers’ tools. An hour before midnight, fifty to sixty armed and masked men surrounded the jail and demanded the guards leave. The guards refused and the mob opened fire. After an hour under fire, three guards managed to sneak away, commandeer a horse and buggy, and get word to Richmond. Meanwhile, the attackers brought up the little cannon the town used to launch fireworks on Independence Day, loaded it with metal scrap, and blew the door off the jail. The four remaining guards retreated into a back room and barricaded themselves inside. When the attackers threatened to bring up the cannon to blow down this door too, the guards surrendered. They were escorted a mile outside of Centerville and released. At four a.m., a train arrived in Centerville with a posse from Richmond. All was quiet; the attackers had gone home. By evening time, there were seventy armed volunteers from Richmond defending the shot-up jail they intended to mine for building materials. A bunch of people were arrested for rioting, and part of the jail was soon disassembled.

Today, Richmond is still the county seat. It has a population of 37,000. Centerville still exists, but has less than a tenth the population of Richmond. On the site where Salisbury once stood you can find the offices of the Wayne County Highway Department and the lot where they keep their construction equipment. Like happened in Centerville, the hastily thrown-up Richmond courthouse soon had to be replaced. The grand Romanesque structure built next door is still the county courthouse today. Weirdly, the county’s first courthouse – the two-story log cabin in Salisbury – spent several years just a few blocks away from both the Richmond courthouses. Before Salisbury failed, the courthouse was sold, torn down, moved to Richmond, rebuilt, covered in cladding, and used as a house. Its identity as the county’s first courthouse was forgotten until someone took the cladding down. It was later moved, but it’s still in Richmond. The remains of the Centerville jail were turned into a library. The shot damage inflicted to its facade during the siege was never repaired; you can still see it on the library today.

When building an RPG adventure inspired by these events, you’ll want to compress these two county seat moves into a single one. A petition got enough signatures to move the seat seat of an administrative division in your fictional setting. Court cases have affirmed the move’s legitimacy, even though the regional commission refused to accept it until enough of the old guard were voted out of office. Now a new courthouse is being built, but it has to be at least as big as the old one, and the citizens of the old seat are stopping surveyors from doing their job. This is where the PCs come in. The newly-elected head of the regional commission wants them to measure the old courthouse. She tells them, “Now y’all handle this measuring however you think is wise. They’re real weird about this county seat business, way too hung up on it. Be careful.” Of course, her faction has gone to considerable trouble to move the county seat just a few miles – they’re as weirdly hung up on it as their opponents are. Figuring out how to get measurements of a building no one wants you to measure is a fun puzzle. If in your setting old blueprints or LIDAR or satellite imagery could render this issue moot, let the party discover that agitators from the old seat have found ways to nullify all those easy solutions. Then the PCs have to organize the movement of the old files from the old seat into a storage unit in the new seat. That triggers a historically-appropriate response by the residents of the old seat. And then they have to guard the old courthouse while it’s being torn down for building materials, again with a historical response.

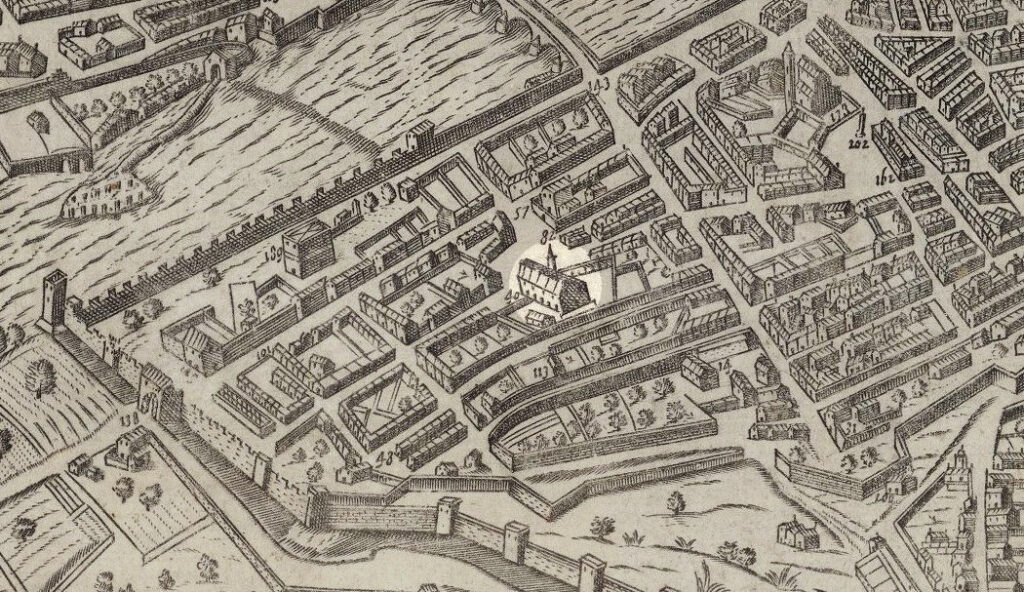

Since the layout around the courthouse matters and the PCs will be returning to the same courthouse several times, a good map will really help this adventure come to life. May I suggest Matteo Florimi’s 1600 map of Florence, Italy? The Carmelite church of Santa Maria del Carmine is a large building on a town square, and has its own walled-in square with gates that can be locked behind the PCs to trap them inside. Here’s a link to the whole map, and the zoomed-in portion just around the church is below.

Some games might benefit from a fictional reason for why the county seat keeps moving. In real life, it genuinely seems to have been civic pride and a vague irritation at the inconvenience of having to travel short distances. If your game is more cynical, that might not work – you’re going to have to make it so that someone stands to make big money from the move. Maybe they own the construction company that will build the new courthouse, or they own the land the courthouse will be built on. If your game is magical, all that business about civic pride (or money) is just a cover. The real truth is that there is a locus of power that’s moving east at about a tenth of a mile a year. Having a courthouse atop it gives the judges who hear cases there secret and terrible magical powers. Of course the locus keeps moving; in a few decades some other town will make a play for the courthouse. In real life, such a locus of power would have crossed the state line into Ohio around 1915 and would presently be under tiny West Manchester, Ohio (population 415).

I’m running a Kickstarter campaign right now for an early-access zine edition of Ballad Hunters. It’s a tabletop RPG where amateur folklorists fight magical folk ballads as agents of the Crown in 1813 England and Scotland.

The folk ballads of the common people are coming to life. Where ballads are sung, sometimes the lyrics take hold of people, forcing them to act out the events of the song. Enchanted victims take on the roles of characters in the ballads. Imagery and danger from the songs manifest supernaturally. Sing old folk songs at the table, anticipate these strange events, mitigate the damage they cause, and help people where you can.

Ballad Hunters is a sequel to the award-winning TTRPG Shanty Hunters and is powered by the GUMSHOE engine. The zine I’m crowdfunding is a small, early-access version of Ballad Hunters.

Source: Wayne County, Indiana: The Battles for the Courthouse by Carolyn Lafever (2010)