In 1694, a mutiny occurred aboard a British ship moored in a Spanish harbor. A group of sailors, led by the first mate, overpowered the captain and those loyal to him. The mutineers set their enemies adrift and, with the rest of the crew apparently behind them, set off to become pirates! Their ship, rechristened the Fancy, would soon conduct one of the biggest robberies in human history up to that point. The story of the mutiny is surprisingly well-documented (thanks to a later trial record with numerous witnesses) and makes a great template for an RPG adventure!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

The ship in question was part of the so-called Spanish Expedition masterminded by the rich British Member of Parliament James Houblon. In an era where the British East India Company was making money hand over fist in the Indian Ocean, Houblon and his fellow investors thought they’d try a scheme of their own in the Caribbean. Houblon’s Spanish Expedition would consist of four ships, heavily laden with cannon, which would sail for the Caribbean, sell some of their cannon to the Spanish military there, and then conduct salvage operations. Hurricanes had sunk many Spanish treasure fleets in the Caribbean and Houblon and his investors believed they could recover the bullion lying in wrecks on the ocean floor. And if, while they were down there, relations between Britain and Spain soured, the ships could use their remaining cannons to do a little privateering: state-sponsored piracy.

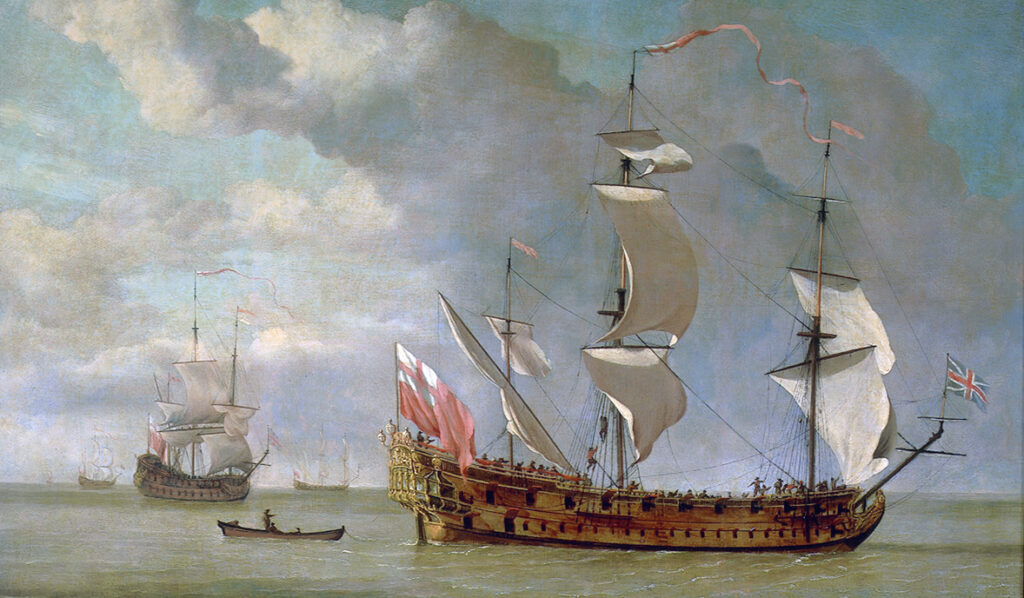

Chief among the four ships was the Charles II, an uncommonly fast 46-gun frigate built specifically for this expedition. She was a little more than a hundred feet long and thirty feet wide at the waist. She had a crew of about a hundred. By the standards of her time, she was a marvel: heavily-armed for her size and as fast as anything else on the water. After the mutiny, the mutineers would remove her protruding forecastle and aftercastle, making her even faster – genuinely uncatchable.

The four crews of the Spanish Expedition drew from the finest sailors in Britain. Houblon offered good wages and promised to look after the sailors’ families while they were away. Plus, if the ships did turn privateer, survivors could expect a share of the booty. It was an attractive package. The original captain of the Charles II had previously conducted a successful salvage operation off Hispaniola – though he would die soon after leaving port and be replaced by an alcoholic named Charles Gibson. The first mate aboard Charles II will later be the protagonist of our story, a Devonshire seaman named Henry Every.

The Spanish Expedition ran into problems almost immediately. In late 1693, the expedition stopped at the port of A Coruña in Spain to take on supplies and handle some paperwork, probably about the salvage or the arms deal. Weeks passed and the paperwork never materialized. Neither did the sailors’ wages, which were contracted to be paid twice annually. Some of the sailors circulated a petition asking for their pay and sent it back to James Houblon in England. Houblon sent word back that the petitioners should be locked in the brig. Back in Britain, Houblon’s promised aid for the sailors’ families also failed to materialize. After several months, some of the families took him to court, asking for their husbands’ back wages. But the Parliamentarian was well-connected enough to escape his contracts. He declared the expedition out of his control and that the sailors were now wards of the King of Spain and none of his concern. Some of the sailors feared the Spaniards would sell them into slavery. I’m tempted to speculate that the Spanish government might have gotten wind of the expedition’s privateer inclinations and deliberately engineered this situation, but I have absolutely no evidence to back that up.

In May of 1694, a conspiracy of sailors plotted action. These men, numbering at least two dozen, had no intention of waiting without pay at anchor in Spain to be sold into slavery. They’d heard tales of the fabulous riches awaiting pirates who preyed on the treasure vessels of the Mughal Empire in India and they wanted a piece. Their leader was Henry Every, first mate aboard the Charles II, and many of the conspirators were aboard that same ship. But others were aboard another ship in the expedition called the James. They’d need to coordinate their actions.

On the night of May 7th, the mutineers took action. It was a moonless night. Captain Gibson of the Charles II was sick in bed, supposedly of a fever, but perhaps just dead drunk. One of Charles’ two second mates, David Creagh, encountered a group of men enjoying a drink down below. One was his superior, Henry Every. Another was William May, a middle-aged man who seems rather cleverer than most of his peers. Second Mate Creagh joined the men for a brief drink, and William May proposed a toast “to the health of the captain and the prosperity of our voyage.” It seems a bit of an odd toast, given the circumstances, and it’s easy to read it as a taunt. Creagh then went to bed, leaving the mutineers to fortify their courage with drink.

Image credit: WarX. Released under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Meanwhile, another mutineer was delivering word to the James that tonight was the night. He rowed over in a longboat and delivered the password: a reference to a “drunken boatswain”. The man on watch aboard the James, first mate Thomas Druit, was not in on the scheme. One wonders what his response was; his trial testimony only says that “I replied short”. The messenger, perhaps not understanding that Druit wasn’t a co-conspirator, elaborated, saying “the ship was going to be run away withal,” then rowed back to Charles II. Druit immediately notified the captain of the James and ordered the pinnace (a kind of boat) be lowered with ten reliable men to interrupt what sure sounded like a mutiny brewing on Charles. But when Druit got to the pinnace, he found that the mutineers had overheard one or more of his conversations. The boat was already manned by mutineers: Druit gives twenty-five, another sailor gives fifteen or sixteen. The two ships were moored within shouting distance of one another. As the mutineers rowed from James to Charles, the captain of the James shouted a warning to the Charles that a mutiny was in progress.

Then things began in earnest. The James fired two cannon shots across the bow of the Charles II. Henry Every, the first mate, ordered the sails unfurled. There was no time to haul up the anchors, so he cut the anchor lines. Before the rest of the expedition (or the Spanish harbor fort) could organize a way to stop Charles, the ship was slipping out of the harbor. Between her head start, the darkness, and her famous speed, no one had a prayer of catching her.

But the mutiny was far from over! The shouting awoke second mate Creagh, but a handful of mutineers, led by Every, shoved him back into his cabin. Once Charles was away, they let him out. Creagh walked to the quarterdeck, where he found Every at the ship’s wheel; the former first mate seems to have been everywhere that night. Every asked Creagh if he’d sail with him and turn pirate. Creagh refused. Several nearby sailors then tried to intimidate Creagh, most notably the middle-aged William May who shoved a pistol against Creagh’s head and declared “God damn you, you deserve to be shot through the head.” The feverish (or drunk) Captain Gibson was awake by this point and Every asked him too if he’d sail with Every on a pirate voyage. In Creagh’s testimony, Every even offered Gibson command of the ship, as long as he’d sail her to the Indian Ocean to turn pirate! But Gibson, like Creagh, refused. So too did fifteen sailors aboard Charles.

Image credit: RootOfAllLight. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Now Every had a hard decision to make. He had seventeen prisoners, including the former captain and first mate, who wouldn’t go along with his mutinous change of plans. The smart move would have been to kill them and dump them overboard. Dead men tell no tales, right? But Every didn’t. Indeed, for large chunks of his pirate career, he declined to commit atrocities against Englishmen – though his atrocities against Indians and Somalis more than made up for it. Maybe he thought he could still turn this around, that like Sir Francis Drake he could be both a pirate and a national hero.

So at first light, Every lowered Charles’ pinnace and seventeen prisoners. Mutineer William May called out to the pinnace, asking the loyalists to remember him to his wife. Some accounts give the parting as jolly and good-spirited. Others report there were many who stayed behind aboard Charles who would have liked to go in the longboat but were held back. One thing was certain: the pinnace that carried seventeen men away from the ship had room for more. The British government later used this fact as evidence that all who stayed behind were consenting mutineers. At the last minute, the seventeen in the pinnace noticed the boat had a hole in it. With ten miles between them and the Spanish coastline, they’d never make it. This was another moment where the mutineers could have left these troublesome witnesses to die. But no, someone did the right thing and tossed them a bucket with which to bail.

(content warning: rape) Every and his crew rechristened their ship Fancy: not in the sense of ‘sophisticated’, but in the sense of a passing attraction. They sailed for Madagascar, then the mouth of the Red Sea. They preyed on ships carrying Indian Muslim pilgrims to Mecca for the hajj. They committed abhorrent deeds (including a days-long gang rape), stole between $200 million and $800 million in today’s money, and then melted away. Of the dozens of mutineers aboard Charles II, only eight were ever caught. They were prosecuted for piracy, but a London jury had trouble believing that theft, murder, and gang rape of Indians was really a crime. The state then prosecuted them for mutiny with greater success. Two were pardoned for turning state’s evidence. The other six were convicted and five were hanged. The convictions came in part from the testimony of some of the seventeen in the pinnace.

One very effective technique when GMing is to know exactly how the story will play out if the PCs do nothing. Then, as the PCs take action, you change things accordingly. The initial course of events gives you a foundation from which to improvise. This makes your improvisation richer and reinforces the idea that the PCs inhabit a living, breathing world that will trundle along without them – and makes the consequences of their actions all the more real.

What’s great about using this technique in a fictional adventure based on the Charles II/Fancy mutiny is that the PCs could make things worse. If they escalate the situation, the captain and his loyalists could easily get killed. Smart players will be real careful how they handle this situation, regardless of which side they take. And that’s great, because it generates tension!

If your PCs find themselves on a ship (or spaceship or sandcrawler, or whatever), you can catch the ship in a bureaucratic tangle that leads to a mutiny. If you like, you can even skip the bureaucratic step and go straight to the mutiny! If the PCs don’t get involved, events play out exactly as they did on the Fancy. But if they do get involved, figure out how that affects things. Maybe they call William May out on his weird toast and prevent the whole mutiny. Maybe they get warning to the fort and the other ships in time for enough warning shots to be fired to bring Every to heel. Maybe they escalate things and the mutiny goes from bloodless coup to bloodbath – though if it prevents later atrocities, could it be worth it? Maybe they even sympathize with Every and help him by subduing the watchstander on the James, only to later regret their involvement.

For over a year now, I’ve been playing in a campaign of Hot Springs Island, a truly excellent OSR hexcrawl. I’ll probably write an End Matter at some point about what makes HSI such an outstanding example of its genre, but today I’m talking about something dumb and unorthodox I did with my character – and how I tried to do it without spoiling anyone else’s fun.

The GM (my wife) set Hot Springs Island in Greek myth. Our characters were shipwrecked on the island while coming home from the Trojan War. The other two PCs are a good fit for the premise: an oracle and an army cook. But I decided I wanted to play an evil character, someone who delighted in wickedness and transgression. That’s a huge red flag. Such characters usually ruin the fun for everyone else, because what they want doesn’t mesh with what the other characters want. As a player, I didn’t want to cause any trouble at the table. I just wanted to cackle a bunch and twirl my imaginary mustache.

So I found a loophole in the morality of the campaign’s premise. Classical Greeks had very different ethical standards than we do. Think here of Aristotle’s argument that most slaves are happier enslaved because they lack the character needed to manage their own affairs. And classical Greeks’ stories about their mythic past had an even weirder (and, to us, more repellent) moral framework. Think of Sophocles’ play Ajax where the eponymous hero commits suicide because he’s so ashamed that Athena kept him from murdering his comrades-in-arms. Ajax’s wife begs him not to kill himself, since she and their baby will be sold into slavery without him around to protect them. But he kills himself anyway. And the play presents Ajax as the good guy! Classical Greek audiences probably saw the play the same way we see King Arthur stories – as depicting a set of values that, while perhaps admirable, aren’t really suited to the modern day.

So if mythic Greek morals are repellent to us, you can make a character who is evil by the standards of his people but moral by the standards of the players. Enter Kakourgeo, the Moth that Gnaws Holes in a Cloak. He introduced democracy to Athens, frees slaves, murders slave-catchers, and connives to elevate women to equality with men. He disdains those who acquired wealth and power through violence (basically all heroes) and strives to tear them down. He’s not doing this because he’s a revolutionary. He genuinely believes what he’s doing is evil. He just likes being wicked!

The other two players are playing characters whose moral framework is roughly the same as their own. Sure, that means their characters have ideals out of line with their fictional, mythological setting, but who cares? As gamers, we do that all the time. And it means that Kakourgeo (a villain by his own admission) and the other two PCs (good guys by their own admission) always find themselves on the same side. Kakourgeo is ridiculous, but he’s not actually disruptive.

What about ideals that are shared between mythic Greece and the modern era? This is where we can take advantage of the fact that Kakourgeo is not a real person. A few sessions ago, the party visited a graveyard. Greek myths make a big deal over honoring the dead. If Kakourgeo were a real person, it would follow that he would want to desecrate all these graves. But he’s not – he’s a fictional character in a fictional story. So what happened instead was that Kakourgeo just didn’t appear onscreen in that scene. If he got some spotlight time interacting with the graves, we’d have to invent a justification for why he wasn’t desecrating them. But instead we just don’t mention it.

As players, we have an obligation to make sure that our fun doesn’t get in the way of other people’s fun. Often that can take the form of coming up with an implausible excuse for why the paladin and the thief can be in the same party. But if there’s a conflict or contradiction that might be disruptive at the table, we can also just… not bring it up.

This story has a disastrous end! Towards an act break in the campaign, it was revealed that – without me realizing it – Kakourgeo was not actually on the same side as the other PCs. I’d barely ever gamed with the other two players before this campaign started. It turned out we were accustomed to very different table cultures, and I was not picking up the signals they were sending me. So in the end while Kakourgeo was not disruptive, neither was he a well-integrated member of the party. I consider the Kakourgeo character a fun and challenging experiment, but ultimately a failure. The campaign is currently on hiatus; when it resumes I’ll roll up someone a little more conventional.

Sources:

Enemy of All Mankind: A True Story of Piracy, Power, and History’s First Global Manhunt by Steven Johnson (2020)

The tryals of Joseph Dawson, Edward Forseith, William May, William Bishop, James Lewis, and John Sparkes for several piracies and robberies by them committed(1696, Library of Congress)