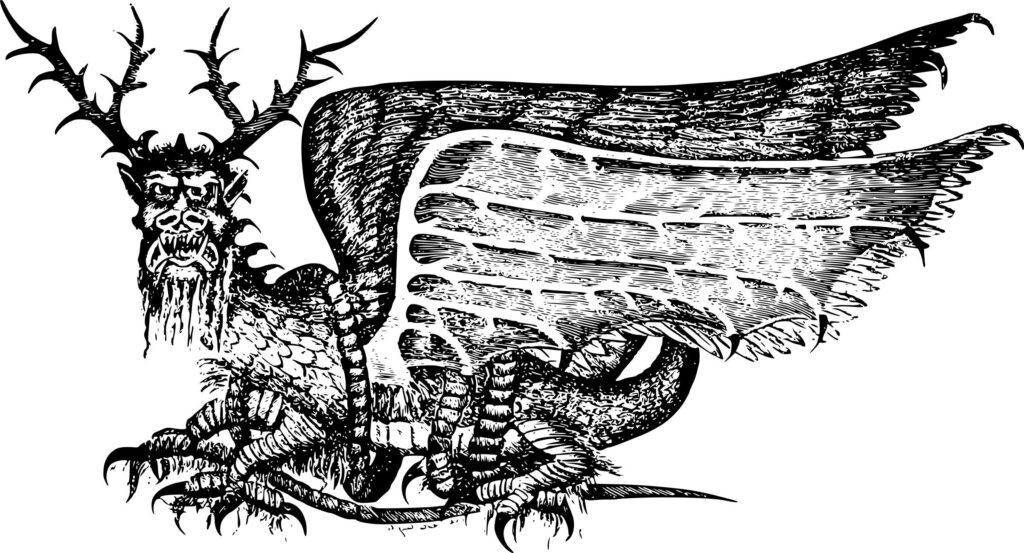

Rocky bluffs line the Mississippi River near Alton, Illinois. Painted on one is a terrible dragon with golden scales, red wings, antlers, and the face of a fanged man. It’s just a replica. The original painting wore away centuries ago – if it ever existed it all! This creature, the Piasa Bird, is a contentious piece of local folklore. If you ask the city fathers in Alton, they’ll tell you the Piasa comes from a real Illini Indian legend, and the original mural was first documented in 1673 by a passing French priest. If you ask local historians, they’re likely to say the Piasa was at best a misunderstanding and at worst a hoax. Let’s dig into this dispute and see how we can use it at the gaming table!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

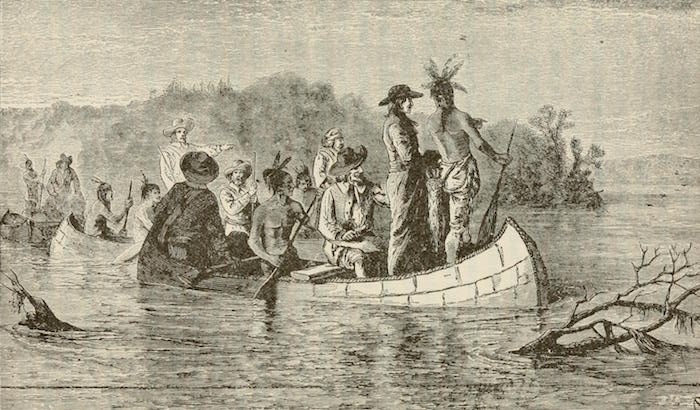

In 1673, Father Jacques Marquette, a French Jesuit missionary, descended from Québec to explore the upper reaches of the Mississippi River. In Wisconsin, representatives of the Menominee nation urged Marquette and his men to proceed no farther south, lest they run afoul of horrible monsters which devour men and canoes alike. We can interpret the Menominee warning as an attempt to preserve their role as middlemen. If Marquette traded with the nations to the south, the Menominee couldn’t resell French goods to their southerly neighbors at a markup. Soon Marquette reached the Mississippi River, where he described meeting a water monster like a great black cat. But it was the paintings on bluffs near modern Alton that really left an impression:

“While skirting some rocks, which by their height and length inspired awe, we saw upon one of them two painted monsters which at first made us afraid, and upon which the boldest savages dare not long rest their eyes. They are as large as a calf; they have horns on their heads like those of deer, a horrible look, red eyes, a beard like a tiger’s, a face somewhat like a man’s, a body covered with scales, and so long a tail that it winds all around the body, passing above the head and going back between the legs, ending in a fish’s tail. Green, red, and black are the three colors composing the picture. Moreover, these two monsters are so well painted that we cannot believe that any savage is their author; for good painters in France would find it difficult to paint so well – and, besides, they are so high up on the rock that it is difficult to reach that place conveniently to paint them.”

Marquette’s claim would soon be challenged (sadly not by anyone pointing out Marquette was a dick). In 1687, two different French missionary expeditions visited the bluffs to view the painting of the monsters. The first said they saw only paintings of a horse and some wild animals. The paintings also weren’t inaccessible, but were easy to touch. The second expedition reported seeing something else: two human figures eight to ten feet high painted in red. Indians traveling with the second expedition “paid Homage, by offering Sacrifice to that Stone”. In 1698, a missionary priest reported the images on the bluffs were almost totally weathered away. No surviving records from the 1700s describe paintings on the Alton bluffs. Presumably they were no longer visible. The local Illini nation (also called the Illiniwek and the Illinois Confederation) was shattered by wars involving the French and may not have had time to maintain the artwork.

In 1836, John Russell, a professor at the local seminary, published The Legend of the Piasa, which purported to be a real Illini legend. According to Russell, ‘Piasa’ (the name of a creek near the bluffs) meant ‘the bird that devours men’. Russell’s story is of a terrible monster and a noble chief, all dressed up in an embarrassing faux Indian writing style (“Many thousand moons before the arrival of the pale faces, when the great magalonyx and mastodon, whose bones are now dug up, were still living in this land of the green prairies…”) Crucially, Russell’s legend claimed that the image of the monster remained upon the bluff. He admitted later that he’d made it all up and didn’t expect anyone would take the story seriously. But the legend was a hit! Other writers breathlessly repeated Russell’s tale as fact. Rival Piasa legends started popping up, none of them any more connected to real Illini stories than Russell’s was.

What’s really interesting about this period is how many people reported seeing the Piasa image with their own eyes. The Alton newspaper itself carried a letter quibbling with Russell’s legend but agreeing that there was a picture of a monster – albeit faded and hard to make out – on those bluffs. All these eyewitnesses agreed the monster on the cliff face had wings – yet Marquette’s description included none. As late as 1824, writers were confirming they saw nothing on Marquette’s bluffs. Yet in the wake of Russell’s 1836 legend, many eyewitnesses – some of whom lived in Alton – reported seeing the painting. Could someone have secretly painted the bluffs between 1824 and 1836? If they did, their handiwork probably didn’t outlive them. Sometime between 1846 and 1867, the Piasa bluffs were quarried away. As late as the 1870s, locals reported having seen the Piasa mural when they were younger.

The first official restoration of the painting of the Piasa Bird went up in 1924. The diminished bluffs have been repainted several times since. Even with modern paints, the mural doesn’t want to stay up – making it even less likely that the painting that folks (maybe?) saw in the 1830s was the same painting Marquette saw in 1673. If you visit today, you’ll find the Piasa Bird overlooks a small parking lot and a granite monument with Russell’s fraudulent legend carved on it.

The likeliest explanation is that Marquette really did see a painting on the bluffs at Alton. We have plenty of contemporary records of other Indian paintings on the bluffs of the Mississippi. A trip down the continent’s greatest river in the 1600s might have been a bit like visiting an art gallery. Marquette just embellished the description, perhaps by folding in memories of French statues of a dragon called the Grande Goule. That isn’t to say the Illini don’t have any stories about creatures like the Piasa Bird. There have been plenty of attempts by scholars to tie the Piasa to (real, still current) Native beliefs in the Thunderbird or the Underwater Panther and to Medieval Mississippian ‘horned serpent’ artifacts. But these efforts are putting the cart before the horse: the documentary evidence suggests there wasn’t actually a Piasa Bird on the Alton bluffs at all.

But that doesn’t explain what was happening in the 1830s! Was there actually an image on the cliff? Did it have wings? Who put it there? I don’t have answers for you.

You’re probably expecting me to talk now about using the Piasa Bird as a monster in your RPG games, and sure – I’ll get to that. But let’s first address the real adventure hook in this story: what the heck was happening in the 1830s? In your fictional RPG setting, invent a minor river town that centuries ago had a neat monster painted on some riverside bluffs. (Maybe. According to some sources.) But suddenly the painting is back! What’s happening? Is it a stunt by the city fathers trying to generate tourism? A portent of the imminent return of the real monster? A gesture by the faithful in an indigenous religious revival? (In real-life 1832, the Illini were briefly granted a reservation in southern Illinois.) Can the PCs figure out the reason for the painting in time? Personally, I’d have the painting be the work of a local preacher who’s trying to inflame his parishioners’ fears that your Illini-analogue are about to undergo a religious and cultural revival. If he can keep his flock furious about Natives getting ‘uppity’, they won’t notice he’s embezzling their donations and preparing to flee.

Alternately, in your fictional setting, what if the contradictory claims are all true, because the image is actually a two-dimensional shapechanging monster? The painting on the bluff today is just a replica, but the original painting/creature is still lurking on a wall or on the ground somewhere. When the PCs come to town to investigate some mysterious disappearances, they’ll naturally suspect that the painting on the bluff depicts a real beast lurking somewhere nearby. It’s the only thing interesting about the town, after all. (No offense intended to the real Alton, which has a beautiful historic downtown and Fast Eddie’s Bon Air, famous for food on a stick and surreal radio commercials.) But the disappearances are actually being caused by a 2D shapechanger emerging from underneath the leaf litter to creep along your walls like a projected image and devour you!

If you want to use the Piasa Bird as a straight-up corporeal monster, consider using the version in Kobold Press’ Tome of Beasts 2. This Piasa is statted up as a dragon with a grappling segmented tail and sleep breath. You might also think about folding in some tulpa powers. A tulpa – at least in the sense used by New Age practitioners and David Lynch – is an imaginary being willed into existence by other people’s belief. The Piasa, being fictional, might be a tulpa generated by townsfolk’s belief that there was a painting on the rock, and that the painting depicted a real beast. Killing a tulpa might be tricky, since if no one sees you kill it, the same belief that generated it once will presumably generate it again in short order. The tulpa concept is derived from Tibetan Buddhism, but that version is a thousand times more complicated and doesn’t bear much (if any) resemblance to its New Age descendant.

Sources:

The Piasa Bird: Fact or Fiction by Wayne C. Temple; Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1956)

Model of the Piasa Bird Is Found in French Museum: Prototype Made in 1640 during Epidemic: Writer Believes Followers of Marquette Painted Alton Bluff by H.W. Long; Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1925)

The Piasa: It Isn’t a Bird! by Natalia Maree Belting; Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1973)

New Thoughts on the Piasa Bird Legend by William G. Fecht; Central States Archaeological Journal (1985)

The Horned Serpent Water Bowls by James E. Maus; Central States Archaeological Journal (2015)