In 1881, Willard Glazier enacted a scam intended to sell books and make his name immortal: he would find the headwaters of North America’s biggest river, the Mississippi. The trouble was, American geographers already knew where the river’s headwaters were, and had for 50 years thanks to the help of the region’s Ojibwe nation. Glazier tried to undermine that knowledge and name his new headwaters after himself, guaranteeing his name would appear in every world geography textbook. Unfortunately for Glazier, his scam was shallow and unsophisticated. He was quickly exposed. At your table, maybe an NPC based on Glazier hires your PCs to help a similar scheme on a fictional river. Can they do better than Glazier did? Or will they sabotage his efforts in the name of truth and fair play?

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Colin Wixted. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Colin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

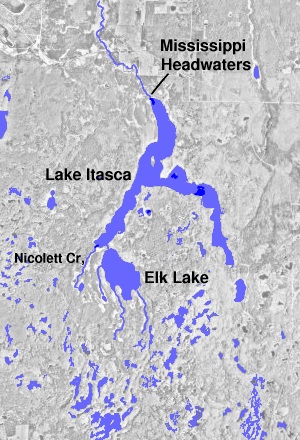

A river’s headwaters are the place it originates, the place it starts being a river. The Mississippi’s headwaters are usually placed at Lake Itasca, in the state of Minnesota. But nature often defies easy categorization. Lake Itasca is fed by several streams, some coming from other, smaller lakes. Itasca’s outflow is bigger than any of these inflows, but not by a jaw-dropping margin. Thus, the identification of the Lake Itasca outflow as being the first time the Mississippi is “really” a river (rather than one of the streams feeding it) is at least partly out of convenience.

Western geographers have historically cared a lot about identifying specific places as headwaters, and a number of Minnesota’s lakes have been labeled the source of the Mississippi through the centuries. In 1832, Ojibwe leader Ozawindib showed an American diplomatic mission led by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft the headwaters at Lake Itasca. Schoolcraft conducted a thorough survey, and western geographers were satisfied. The Mississippi’s headwaters didn’t have to move anymore.

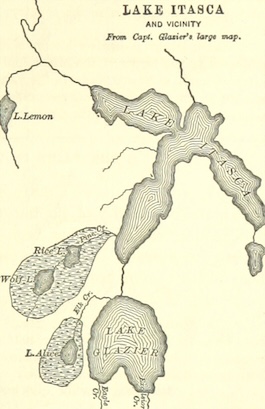

In 1881, Willard Glazier, a Civil War captain and professional author, set off on an expedition to the (well-mapped) headwaters of the Mississippi, publicly declaring he intended to discover where they really lay. At the completion of his journey, he spent one whole day paddling around Lake Itasca in a canoe. He came across a stream, today called Chambers Creek, which led to a place called Elk Lake. This lake had been appearing on maps for 45 years, and Chambers Creek is only 200 yards long. But Glazier saw an opportunity. He announced in the press that he’d found a previously-undiscovered lake, which he humbly named Lake Glazier, and that as Lake Glazier fed Lake Itasca, Lake Glazier was the real headwaters. He and his friends launched a spirited PR campaign for Lake Glazier, and Glazier himself wrote several books to shore up his claim.

Glazier’s claim attracted a little more attention than he perhaps anticipated. It was soon noticed that he’d plagiarized large sections of his books from Schoolcraft’s original book on Lake Itasca. It was also noticed that a lake (Elk Lake) had been appearing on maps in a suspiciously identical location to Lake Glazier almost since Schoolcraft’s first publication. And some readings of Schoolcraft’s survey suggest that the reason Elk Lake doesn’t appear on it is that at the time Elk Lake was just an inlet of Lake Itasca; the isthmus that today separates the two had not yet silted in.

In the years that followed Glazier’s “discovery,” two survey expeditions traveled to Lake Itasca. The first was sent by a New York publishing house. Since Glazier’s books were big money, the publishers had a vested interest in knowing if they were true. The second was from the Minnesota Historical Society, which was upset Glazier was impugning the honor of the state’s idolized explorers. Both explorers found that Glazier’s claim was bunk. Lake Glazier was just Elk Lake, and Chambers Creek had no greater claim on being the Mississippi than any of the other creeks flowing into Lake Itasca. Indeed, if your criterion was not volume but length, Chambers Creek was arguably the least Mississippian of the Itasca feeder streams.

The claim that Lake Glazier was the real source of the Mississippi never caught on.

At your table, an NPC inspired by Willard Glazier might want to pull a similar scam on a river in your fictional setting, aiming at book sales and his legacy. He might sign on the PCs as guides, porters, muscle, and to run a few dirty tricks. Slap a map of your headwaters on the table. Tell the players that it’s a map from a recent survey and it precisely matches what they discover when they arrive on the scene. How do they advise the Glazier-analogue? Can they come up with a scheme harder to refute than his? Or do they humor him until they get back to town, then sell him out to the state historical society? As a well-read novelist and ex-army officer, Glazier probably has a few well-placed friends who can make trouble for the party if he learns they crossed him.

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Sing and fight magical folk ballads in 1813 England and Scotland! This free early-access edition has everything you need to play a Ballad Hunters one-shot about the traditional song Barbara Allen.

The game has:

– Investigative adventures centered around the lyrics of traditional British ballads

– Simple, story-driven rules inspired by the GUMSHOE engine

– A historical setting that is grim but hopeful

– Magic where characters make ballad verses come to life

Ballad Hunters is the sequel to Shanty Hunters, winner of a 2022 Ennie Award (Judge’s Choice) and nominee at the Indie Groundbreaker Awards for Most Innovative and Game of the Year.

You can download the free early-access version of the game from DriveThruRPG or Google Drive.

Sources:

The Search for the Great River’s Source: An Account of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s Expedition to the Source of the Mississippi River — Lake Itasca (1982)

Lake Itasca State Park, updated interpretive signage