From 1879 to 1881, a French nobleman found several hundred willing dupes, took their money, and packed them off to a nation he’d made up. Dazzled with promises of land and ease, these peasants found only pestilence and death beneath the hot Pacific sun. The audacity of the scam, the ambiguous motives of the scammer, and the jaw-dropping body count all combine to make this one heck of a story – and potentially one heck of an RPG adventure!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

We open with our villain: Charles Marie Bonaventure du Breil, the Marquis de Rays. He was born in 1832 to an aristocratic family in Brittany, the peninsula in northwest France. His family had suffered under Napoleon and the Marquis grew up close to penniless. Supposedly, a fortune-teller once told him he would be king of a utopia. At some point in his life, he seems to have genuinely believed in some sort of utopian ideal – though his version of utopia still had a monarch, dogmatic Catholicism, white people on top, and aristocrats on top of them – but if he ever did genuinely believe in these things, ideals gradually gave way to a need for cash. He tried managing a ranch in America, trading peanuts in Senegal, and trading hard goods in Madagascar and Southeast Asia, but all his ventures failed.

In 1877, the Marquis de Rays settled on a grand union of his utopian vision and his scrabbling for money: he would found a utopia in the Pacific and people would pay him for it. We may wonder whether he knew from the beginning that this would be a scam. I’m inclined to believe that a man can both intentionally bilk people for all their money and simultaneously believe he is doing right by them. In any case, the dispute is academic; he would fleece hundreds and kill most of them. He first decided his colony would be in Western Australia, believing it was unclaimed and uninhabited. Of course, it was claimed (by Britain) and inhabited (by Aboriginal Australians). His friends managed to convince him that Britain would treat a new colony in western Australia as an invading force, and he shifted his plans.

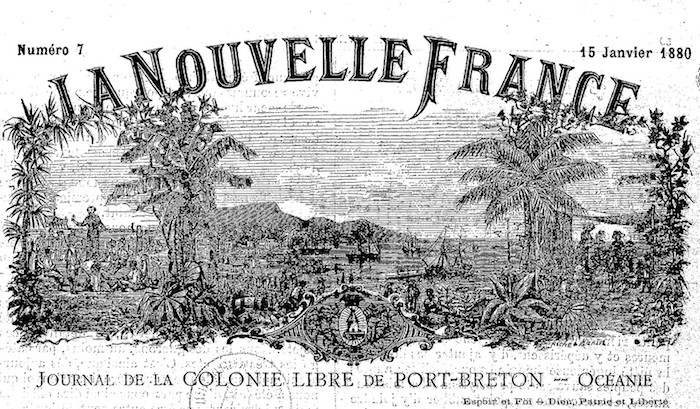

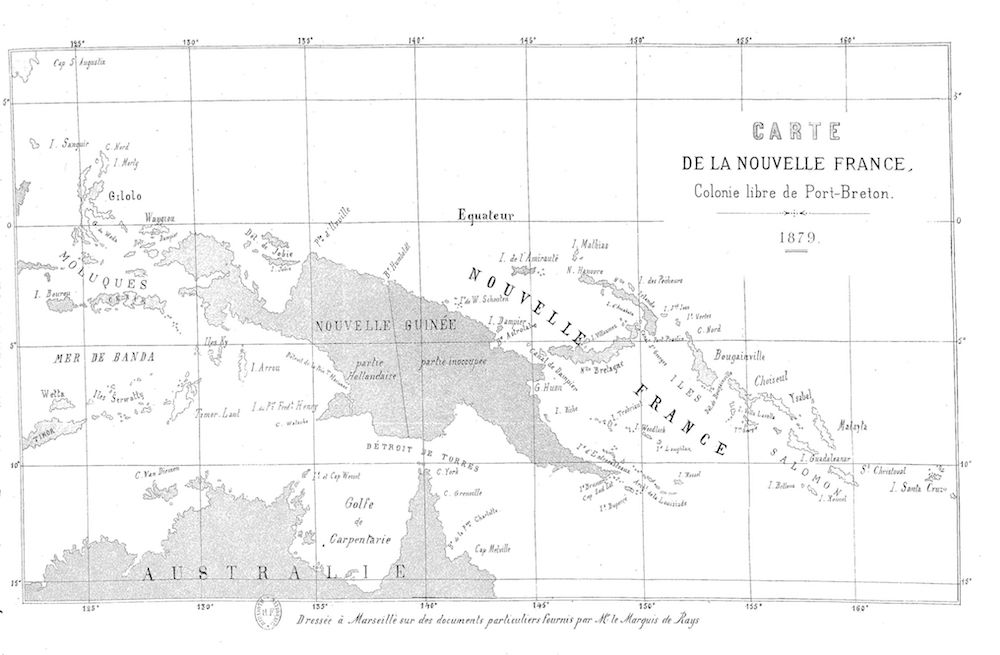

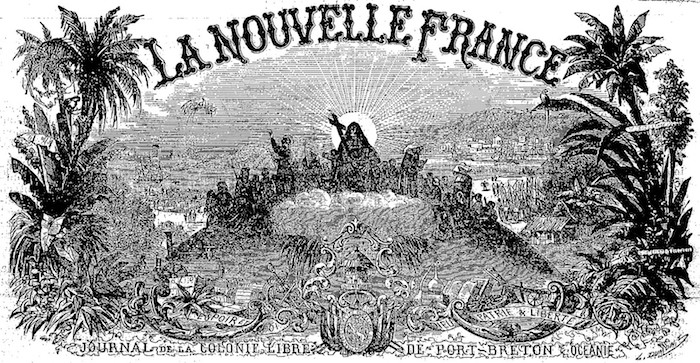

So the Marquis de Rays announced the creation of a new colony/nation: New France, stretching from New Guinea to the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific. Its headquarters were at Port Breton, a place he invented on the real island of New Ireland, northeast of New Guinea. Crucially, the Marquis wasn’t announcing he would found such a colony. He announced that he already had: that there was a prosperous settlement at Port Breton, and that Catholic missionaries were already venturing into the interior of New France. Not a word of this was true.

Illustrated pamphlets and literature invited colonists to join the imaginary settlement at Port Breton. For 1,800 francs (300 contemporary U.S. dollars), you got transportation to Port Breton, fifty acres of land already cleared and ready for cultivation, and a four-room house already built and waiting for you. If you couldn’t afford that, you could work for five years at the colony and earn it. But don’t worry about the work, because imported Chinese and Malay coolies would do all the real heavy lifting. Port Breton was supposedly a paradise. The weather was always mild, the soil was perfect for farming, disease was unheard of, and there were no natives. It was all lies. The spot on the map selected for Port Breton was a pestilential swamp. The soil was almost all sand. And the forested interior of the island was heavily populated by local New Guineans – none of whom were fools enough to live in that swamp.

The Marquis de Rays set up a charter to establish a government for New France. He was at its head, as the divinely-selected King Charles I. He could not, sadly, live in his new nation as he had business that kept him in Europe. But just as soon as that was squared away, he would rush to Port Breton with his family. His laws were final and unappealable, but there was no risk of tyranny, as his rules were inspired by Christian sentiments that the (definitely real) colonists agreed with. Monks of the Carthusian and Trappist orders would carry out the day-to-day administration (just as soon as they got there). Once things really got up and running, French nobles would come over to occupy the rung below the monks. Below that would be non-noble Catholic white settlers, and below that would be the supposed Chinese and Malay coolies.

So the Marquis de Rays went looking for settlers for Port Breton. And plenty of folks were swayed by the promise of beautiful weather, plenty of fertile land, and coolies to do the hard work for them. The first ship to Port Breton, the Chandernagor, carried 80 emigrants (all male). The French government suspected this business was a scam and wouldn’t let the ship leave port with emigrants aboard her. So the Marquis re-flagged the ship as American and had the settlers board her in the Netherlands. Before Chandernagor even reached Port Breton, the Marquis announced the success of the expedition and raised the price to buy in. The ship landed in January, 1880. There was no cleared land, no pre-built houses, and no coolies to do the work for you. There was just a swamp. Mercifully, there was no immediate conflict with the locals, since they didn’t live in the place the settlers were now trying to clear. In a few months, 50 of the 80 emigrants died of disease and starvation. The surviving 30 got back aboard the Chandernagor and sailed to the other side of the island, where they resettled at a pre-existing Methodist mission.

The next ship, the Genil, left Europe carrying 50 emigrants. The ship’s master, Captain Rabardy, handed out cruel punishments for trivial offenses. He was also supposed to take over Port Breton when they got there. The emigrants were less than thrilled at the idea of spending years living under this tyrant, and most jumped ship in different ports along the way. The few who remained arrived in Port Breton in August, 1880 to find no evidence of European habitation – except 50 graves from the Chandernagor emigrants.

The third ship, India, was a celebrity in her own right. Under the name Feret, she had supposedly been lost at sea. There was a sizable insurance payout, and then she was discovered – renamed and repainted – in the possession of a new owner: the Marquis de Rays. It was a big scandal. When she left for Port Breton, India was carrying 350 (ish; I’m not confident in these numbers) Italian peasants and artisans recruited from villages north of Venice. The recruiting agent made some remarkable claims and the region was wracked by war, so there was no shortage of recruits. The India emigrants landed in October, 1880, joining the few from Genil.

This phase of the scam is the best-documented. In unloading India, it became clear how little attention the Marquis had paid to the nitty-gritty of founding a settlement. There were boxes of knife handles without knife blades. There was machinery for a sawmill, but no axes. There where wheelbarrows without wheels, bricks for a cathedral, machinery for steam power – but no quinine. This last bit is the craziest to me. Quinine is an anti-malarial drug. When you read accounts of European attempts to colonize the tropics, what jumps out at you is death after death after death from “fever” (malaria). And it’s not like this was a secret back in Europe. The bricks for a cathedral to me scream ‘well-intentioned idiot’. The lack of quinine screams ‘murder’.

Things went about as badly as you’d expect. Some folks got along with the locals, but others tried to push into the already-densely-populated woods. There was violence, and the locals started raiding Port Breton. The settlers gave up on building houses and instead built a blockhouse that was equal parts guardhouse, dormitory, infirmary, and church. Though folks worked hard to clear land for farming, unending rains washed away all attempts at cultivation. Disease, starvation, and raids whittled down the number of people in Port Breton. Captain Rabardy, the on-site commander, went mad.

Many European ships plied the Pacific, and some stopped in Port Breton. Their crews and passengers didn’t know what to make of what they saw. Some ships carried messages from the Marquis de Rays, but they were nonsensical: setting aside land for the palaces of the nobility or directing the colonists where to build their cathedral. These ships carried word back to Europe. There were newspaper articles about the disaster. The French government started making noises like they’d arrest the Marquis, but he’d relocated to Spain. Nonetheless, he put together a fourth ship, Nouvelle Bretagne.

In February, 1881 – four months after India arrived – the 250-ish survivors climbed back into their ship to get the hell out of Port Breton. India had suffered damage in the interim and was no longer seaworthy. The survivors limped to Nouméa in the French colony of New Caledonia. They ran out of food and water along the way and more died. The survivors (217 in all) were relocated to Sydney. The Italian survivors asked to be given land together, but the Australian government was leery of creating a non-English ethnic enclave. So instead, the Italian survivors spent several years independently buying land about 500 miles north of Sydney, creating a little community they called New Italy.

Nouvelle Bretagne arrived to find New France abandoned (again). 150 settlers from the ship set up shop, then endured the same fate as their predecessors. The 38 survivors were evacuated to Sydney.

The Marquis de Rays was arrested in Spain and extradited to France. He spent five and a half years in prison. Several of his underlings were also sentenced. After prison, he lived for five more years. He spent them on other fraudulent schemes, including a luxury cruise, selling granite powder as gunpowder, and romancing rich American women out of their money. Britain and Germany split the territory of New France between them and the whole affair ended.

At your table, a version of the New Breton scam fictionalized for your campaign setting might make a good mystery. Someone is selling land in a nation no one has heard of. It’s not impossible the sales are legit, and the seller seems very well-intentioned. But when an NPC the party cares about (or is paid to care about) announces her intent to settle in this new nation, the PCs have to figure out what’s happening in this far-off land. Alternatively, they might hear of the expedition from someone who deserted from the second voyage or be sent on assignment by your setting’s equivalent of the French police.

You might also use the expedition as an encounter the PCs have while traveling. They meet your setting’s version of the leaky India fleeing Port Breton for Nouméa. The PCs can help fix the ship and offer supplies. If the players find the situation interesting, they can follow up. Maybe they get to your version of Port Breton just in time for the final ship to arrive, much to the fury of the locals (“How many times do we have to go through this?”). Or maybe they go to your France-analogue and are the first to break the story about what’s going on in New Breton.

–

Sources:

Utopian Fraud: The Marquis de Rays and La Nouvelle-France by Bill Metcalf. Utopian Studies, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2011

Phantom pacific paradise: was the Marquis De Rays’ New France a Cleverly plotted scam or a fantasy that went horribly wrong? by Jordan Goodman. Geographical, Vol. 83, Issue 6, 2011