Genghis Khan, the founder of the Mongol Empire, was one of the most historically-significant humans to ever live. Yet we have no idea where he was buried. His lost resting place – and the possibility it contains the finest loot from a lifetime of conquest – makes a great adventure hook.

The West remembers Genghis Khan as one of the most bloodthirsty conquerers in human history. That’s true. His empire stretched from the Caspian to the Sea of Japan. Under his descendants, it spread farther still. By some calculations, his massacre of Khwarezmid Persia was so extensive that Iran didn’t regain its pre-Mongol population until the 20th century. But he also promoted religious tolerance, secular law, and international trade, and his conquests ushered in centuries of peace in the regions that submitted to him. He’s something of a mixed bag. But no one would deny the extent of his influence.

Genghis Khan died in 1227 while pacifying the rebellious state of Xi Xia. How he died is unclear. Our best source, the 13th-century Secret History of the Mongols simply notes his death and rolls smoothly into the dynastic succession. The first Papal legate to Mongolia reported that Genghis Khan was struck by lightning. Marco Polo reports he died of an infected arrow wound. You see claims as varying as a fall from a horse, typhus, poison, a magic spell, and a Xi Xia queen who hid a knife in her vagina so she could lethally castrate the Khan when he raped her.

Genghis Khan’s soldiers brought his body home to Mongolia, and buried him in an unmarked grave. According to tradition, the burial location was supposed to be secret. One legend recounts that the soldiers in the funeral cortege killed everyone they encountered on their voyage home, rode hundreds of horses across his grave repeatedly to ensure it could never be found, rode elsewhere to be killed by another set of soldiers, who themselves either committed suicide or were killed by a third set of soldiers. It’s a ridiculous story, of course, but it illustrates the Mongol popular perception of how seriously they were supposed to take this secret.

Traditionally, Genghis Khan was supposed to have been buried somewhere on or near the mountain of Burkhan Khaldun, in a region called the Ikh Khorig (‘Great Taboo’). This heavily-wooded, mountainous region was off-limits to all but relatives of the Great Khan and a specific tribe instructed to enforce the prohibition. Even after the Mongol empire fell, locals refused to allow anyone to enter the Ikh Khorig. Even the Soviets respected the taboo, albeit for their own reasons: keeping everyone out of the Ikh Khorig prevented it from becoming a rallying point for Mongolian nationalists.

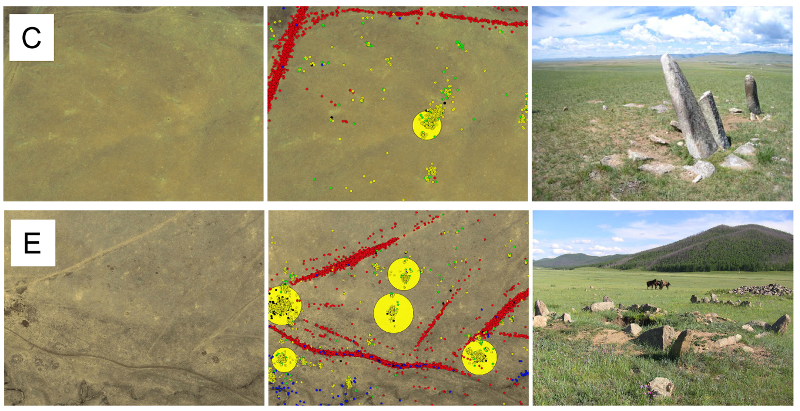

What might the tomb look like? The Xiongnu, a steppe nomad people who lived in what is today Mongolia over a thousand years before Genghis Khan, buried their kings in log-walled chambers 20 meters underground. Their tombs contained treasures and trade goods from as far away as Rome. The Xiongnu placed stone markers above their royal tombs. If the Mongols inherited or imitated the burial practices of their predecessors, but chose to omit the marking stones, Genghis Khan’s tomb might be completely unfindable.

There’s been an enormous amount of adventure writing on the Great Khan’s tomb. Some folks identify an oval rockpile at the peak of the sacred mountain as a possible location. Others say it’s a completely natural geologic formation. Either way, the Mongolian government isn’t permitting excavations. Multiple Westerners have organized expeditions all over Mongolia, chasing down pet theories and questionable claims in later manuscripts. Some are in it for the adventure. Some are in it for the history. And some are in it because of unsubstantiated beliefs that Genghis Khan may have been buried with fabulous grave goods looted from some of the greatest cities of his day.

One particularly interesting search was a ‘citizen science’ effort that leveraged 10,000 online volunteers to search for “out of the ordinary” features in satellite data across 6,000 square kilometers near the Ikh Khorig. A National Geographic expedition to investigate the identified features confirmed 55 ancient sites. The paper’s worth a look. It reads like they were serious about finding the tomb, but since they didn’t find it, they wrote instead about the neat new form of crowdsourcing they developed.

The tomb here is plot hook, not adventure site. The countless conflicting legends, the satellite searches, the adventurers conducting excavations across Mongolia – all these are not avenues to pursue. They’re context. They’re proof that conventional techniques will not solve this problem, so the PCs are going to have to try something wildly unconventional. Then, should they succeed, the dramatic history of folks failing to find the tomb will make the party’s success all the more enjoyable.

In an urban fantasy game, your PCs might use divining rods or try to contact the Tengrist spirits Genghis Khan worshipped. In a science fiction game, your party might infiltrate a government space station that scans the earth and reprogram its sensors to look for Mongol graves. My PCs took a time machine back to Genghis Khan’s death, infiltrated the funeral procession, rode with the Mongols all the way to the burial site, and returned later to excavate it.

If you want to put grave goods in your version of the tomb, it would be a lot of fun to include loot from the Khan’s many conquests. However, given that Genghis Khan died on campaign, and was quickly returned to Mongolia, it’s unlikely there’s anything bulky inside his tomb. He probably wouldn’t have brought anything truly grandiose with him to war. And anything huge would have slowed down his body’s rapid return to Mongolia.

Still, you can include a lot of fun grave goods. If he’s buried with anything, my bet would be on lovely baubles: the sorts of highly portable wonders a soldier might loot in one place, then carry with him in case he wants to trade it for a horse or a slave. One can imagine his bodyguards and soldiers dropping their contributions into sacks to be carried with the body back to Mongolia. Some examples might include:

– An alabaster belt plaque carved with the image of a dragon, looted in Xi Xia

– A gold bracelet etched with the image of songbirds, with inlaid jewels for eyes, looted in Qara Khitai

– A jade lion looted in Jin China

– An obsidian pharaoh’s face the size of a silver dollar, of Egyptian manufacture, looted in Khwarezmid Persia

– A palm-sized gilded Theotokos icon from the Kievan Rus

– Someone’s collection of souvenirs from their travels: a bag of silver coins from across the Mongol Empire, each bearing the face of a different king. Some of the kings were dead for 300 years by the time of their kingdoms’ conquest. Some were killed by the Mongols themselves.