The word ‘thug’ arrived in English in the early 1800s to refer to a specific kind of bandit operating in India. The concept of ‘thugee’ (the practices of thugs) soon lodged itself in the Anglophone popular consciousness, spawning media like Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. But real-life thugee was very different from the (racist) thugee in the pulps and papers, and some historians today argue that it never even existed. Inasmuch as thugs and thugee can be said to have existed, it is counter-argued that it did so as a sort of patron-sponsored banditry carried out in foreign lands. This argument is a really compelling twist on the common human practice of out-of-work mercenaries becoming bandits. Whether or not this particular interpretation of thugee winds up carrying the day among historians, it’s super interesting. If you file the serial numbers off it (and change the name), this version of thugs makes a great collection of bad guys to drop into your ongoing campaign – and one with a baked-in plot hook that generates its own adventure.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

This post lies on shaky ground for me to be writing about. The idea of thugee was first popularized within the East India Trading Company (the privately-operated British colonial authority) in the early 1800s by an employee named William Sleeman. He was looking to advance his career, so he got the Company scared of thugs, then got himself appointed its India-wide thugee-stopper. Some historians argue Sleeman (or officials like him) made the whole thing up, and that the idea caught on only because it fit well with the Company’s fears and anxieties. We may be certain that the depiction of thugee in popular media owes more to Sleeman’s hyperbole than it does to any real truth. But other historians, especially those who’ve gone through the transcripts of Sleeman’s interviews with his informants (who often identified themselves as thugs) argue that just dismissing thugee is too facile. They argue that Sleeman’s informants were referring to real bandits who existed in a special place on the vast continuum of banditry – even if those bandits didn’t always look, act, and believe as Sleeman claimed they did.

So what do I mean when I say ‘thug’ and ‘thugee’? Drawing on the work of historian Kim A. Wagner, when I write of ‘thugs’, I am referring to the real people that Sleeman’s Indian informants were talking about, regardless of whether those people actually resembled Sleeman’s interpretations. When I write of ‘thugee’, I am referring to what thugs actually seemed to have been getting up to, regardless of whether Sleeman would agree.

And I’m not going to spell out the colonial or the pop culture version of thugee. I’ve seen too many studies that suggest it’s counterproductive to fight misinformation by first repeating the false claim, then arguing against it. Too often, readers remember seeing the false claim appear in a source they trust, but forget the refutation. The refutation is usually less sexy, and therefore doesn’t stick as well in the mind. Worse, some readers hadn’t previously been exposed to the misinformation, but your well-meaning attempts to fight it just spread it further. So this post is me trying to talk about thugee without perpetuating a two-hundred-year-old bigoted falsehood.

Real thugee seems to have grown out of a longstanding network of itinerant Indian mercenaries. The East India Trading Company was expanding across the subcontinent, conquering some Indian nations and coercing others into becoming defanged client states. This meant there were fewer Indian armies, and therefore fewer jobs for mercenaries. And while the Company was growing its own army, its hiring policies kept out most of India’s existing mercenaries, many of whom came from families that had been mercenaries for generations. Meanwhile, these defanged client nobles were not thrilled to have lost out on the money they used to make launching raids on wealthier areas.

So nobles and big landowners (the zamindars) in northern India seem to have started hiring mercenaries as retainers. The patrons would pay to outfit expeditions to richer parts of India, where the ex-mercenary thugs would rob people on the road, especially traveling merchants. Back at home, the patron supported the thugs’ families. After months on the road, the thugs returned to their zamindar patrons and offered up a share of the loot. Naturally, this share didn’t always cover the expenses the patron incurred (or claimed to incur) on the thugs’ behalf, trapping thugs in a cycle of debt that forced them into expedition after expedition. Of course details differed in different times and places. But if you think of thugee as being a sort of covert, foreign-state-sponsored banditry, you’d probably be within the bounds of documentary evidence.

Not all thugs were out-of-work mercenaries. Many were, of course, and saw thugee as being no different from their regular family business: you sign on with a noble, go on expedition to commit violence on his behalf, then come home. But any man could be a thug if he could find a patron. Peasants, servants, slaves, pilgrims, yogis, Hindus, Muslims – even zamindars – have all been documented as practicing thugee. Some thug bands may have been based around a nucleus of related hereditary mercenaries, but the group’s overall composition could be fluid.

Thugs often killed their victims and hid the bodies to make their crimes harder to prosecute. Their most common tool seems to have been strangulation. It’s quiet. When you wrap your fingers (or a cord, or the cloth from your turban) around someone’s neck, there’s no screaming to alert passers-by. That said, every thug was different, and plenty used clubs, knives, poison – or even just threats and intimidation. All that really mattered was that you got away with your victim’s stuff. If you could lie well enough to get your victim to go off alone with you, often by offering to travel with them for mutual protection, they were as good as yours.

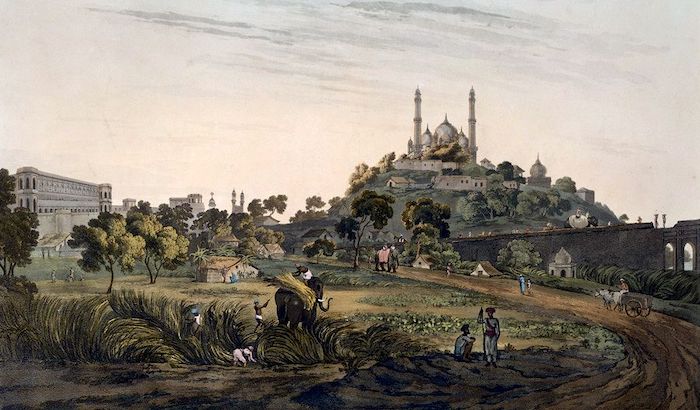

One of the most gameable instances of thugee is also – not coincidentally – one of the ones better supported by Indian voices. The village of Sindhos lies on the western border of Uttar Pradesh, 60 miles from Gwalior. In the early 1800s, a sizable fraction of the families in Sindhos earned their living by thugee. In 1810, about 20 years before the Company got thug fever, a British magistrate interviewed Ruheem Khan, the superintendent of police at Sindhos. Khan claimed that of the 15,000-20,000 people who lived in Sindhos and neighboring villages, several hundred families sent men to work for the local zamindars as thugs. The zamindars maintained absolutely usurious practices: offering loans with 100% interest and counting stolen loot against that debt at only half its value. This kept the people of Sindhos trapped in a cycle of debt, and may have driven some families to send ever more sons into thugee in the hopes of paying off their ballooning debts.

Police superintendent Khan claimed that Sindhos’ thugs focused their attentions about a hundred miles east of the village, in the rich lands near Kanpur and Allahbad (Prayagraj). They traveled in different disguises. In small groups, they’d get hired on by merchants as servants and porters, or they’d masquerade as merchants to hire servants – either way with the intent of robbing and killing those they deceived. In larger numbers, they’d even masquerade as army units, so people would seek them out as traveling companions. Sometimes they’d bring the loot home directly. Other times, they’d sell their stolen goods in the marketplace and bring home the money. You could call this ‘masquerading as merchants’, but if you’re selling goods in a market, I feel like that’s not a masquerade anymore.

In 1812, Laljee, the biggest zamindar in Sindhos, was arrested by the British for hiring and retaining thugs. We have the transcript of his examination. I certainly don’t want to claim that Laljee was definitely a patron of thugee based on this interview. He comes across really badly in it, but lots of people say stupid stuff in police custody and confess to crimes they didn’t do. Nonetheless, in his interview, Laljee confirms the broad strokes of what police superintendent Khan had said: the zamindars of Sindhos retained thugs and took enormous cuts of their loot.

There’s other support for the idea that Sindhos was a hot spot for thugee, but those are the two sources I wanted to highlight.

At your table, these guys make a really cool take on bandits. When you’re filing the serial numbers off them so they can fit better into your fictional RPG campaign, you’d be well-advised to make sure you change their name. Obviously ‘thug’ has become a generic term in English for ‘bad guy’. But it’s also really racially charged. At least where I am in America, it’s often used to describe young black men, often casting them as criminals based on their appearance and age alone. So even setting aside all the Indiana Jones stuff, it’s probably best if you invent a made-up word to refer to your setting’s landowner-sponsored bandit expeditions.

While thugee and those who practice it are certainly bad, the really bad dudes are clearly the patrons: the nobles and big landlords who hired thugs and kept them trapped in cycles of debt that sent them out again and again to rob and kill. I’m not saying that everything would have been hunky-dory had the zamindars just refrained from patronizing thugee. Northern India still had a problem with out-of-work mercenaries and with bandits. But it’s hard to imagine that zamindars like those in Sindhos weren’t actively making things worse.

So you throw your fictionalized version of thugs at your PCs while they’re traveling. The party gets to have a memorable fight with some bandits who are very clearly Bad Dudes, yet have more complex stories and traditions than the usual RPG conception. And if the party gets a chance to talk to one of them (or talk to someone else about them), they get the plot hook that these bandits were retainers for a rich and powerful person in a decently far-off land. Hopefully the PCs decide to act on the information, because then they’ll get to travel to that far-off land while thugs (who’ve wised up to the party’s intentions) try to accompany them and strangle them on the road. At the rich person’s village, the PCs get to fight through waves of thugs to reach the mansion – or maybe try to turn the thugs, pointing out that if the patron were to disappear, so would everyone’s debts. Naturally, inside the patron’s mansion the party stumbles upon all this accumulated loot. Do they keep it? Do they distribute it to the villagers? Is there any hope of returning some of it to the victims’ next of kin?

–

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Sing and fight magical folk ballads in 1813 England and Scotland! This free early-access edition has everything you need to play a Ballad Hunters one-shot about the traditional song Barbara Allen.

The game has:

- Investigative adventures centered around the lyrics of traditional British ballads

- Simple, story-driven rules inspired by the GUMSHOE engine

- A historical setting that is grim but hopeful

- Magic where characters make ballad verses come to life

Ballad Hunters is the sequel to Shanty Hunters, winner of a 2022 Ennie Award (Judge’s Choice) and nominee at the Indie Groundbreaker Awards for Most Innovative and Game of the Year.

You can download the free early-access version of the game from DriveThruRPG or Google Drive.

–

Source: Stranglers and Bandits: A Historical Anthology of Thugee by Kim A. Wagner (2009)