Sir John Mandeville was an English knight who claimed to have traveled broadly in the mid-14th century. Among other things, he reports soldiering in the service of the Fatimid Caliph in Cairo and for the Emperor of the Yuan dynasty in China. The actual extent of his travels is unknown, but along the way he picked up some really fantastical details, some in the vein of ‘I heard it from a guy who heard it from a guy’, and others of the ‘I totally saw this, you have to believe me’ variety. Eleven of the most gameable of these details are below.

Mt. Etna (Sicily). There are vents on the island that gush color-changing flames. The people of the island observe the colors of the vents to augur the future. Furthermore, the vents are the entrance gates to Hell. Skilled PCs may be able to use the vents to attempt prophecy.

Sicily. There’s a snake on the island that can tell if you were born out of wedlock, and husbands use it to check if their wives are faithful. They put their children in front of the snake. If the child is born of married parents, the snake won’t bother it. But if the child is a bastard, the snake will bite it! (These same snakes show up in North Africa in Pliny and in Malta in the Golden Legend.) This snake is more plot hook than monster. ‘Please go catch this snake so I can use it’ is a great way to spring a surprise on a PC when she gets bit trying to catch it. Or maybe an heir to a throne or fortune gets bit, prompting a chaotic reshuffling of the local social order, which the PCs can try to influence or exploit.

Cilicia (Turkish coast). There is a great city that sank into the sea because of the foolishness of one young man. He loved a woman, but she died suddenly, and he went into her tomb to sleep with her corpse. Nine months later, he heard a voice commanding him to re-enter the tomb and see what he had begotten on her. When he slid the bier open, a hideous human head flew out! It sailed all around the city, and the whole place collapsed into the ocean, leaving many dangerous channels and canyons. This could be a fun plot hook! In a city that hasn’t yet sunk into the sea, the PCs can figure out what the young man has done, try to anticipate the consequences, and fight the head before it destroys the town!

Tyre (Lebanon). Rubies sometimes wash up on the shores of Tyre. Where could they be coming from, and who might you have to battle or outsmart to find them?

Arqa (Lebanon). A river here runs fast on Saturdays, but otherwise runs little or not at all. A stream in the same hills freezes solid every night, but during the day no frost can be seen.

Jaffa (Israel). The city is named for Japheth, a son of Noah, and was founded before the Flood, making it the oldest city in the world. The town is built on the bones of a giant named Andromeda. One of his ribs is forty feet long!

The Fosse of Mynon (Acre, Israel). A circular pit 150 feet across, full of gravel. No matter how much you remove, the next day it’s always full again. There’s always a great wind in the pit, which blows the gravel around. And if anything metal is put in the pit, it immediately turns to glass.

The Dead Sea (Israel/Jordan). The color-changing waters of the sea daily vomit up horse-sized lumps of asphalt that float to shore. The physics of the sea are arbitrary and often inverted. If you throw in a lighted lantern, it floats, but an unlit one sinks. Iron floats. Feathers sink. And boats will immediately sink, unless their hulls are coated in pitch.

Image credit: Keith Chan

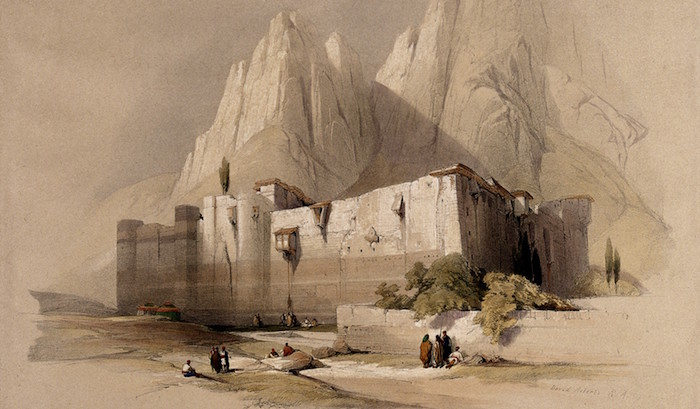

Mt. Sinai (Egypt). The Monastery of St. Catherine, at the foot of Mt. Sinai, is a fortified compound that holds the bush that Moses saw burning and the body of St. Catherine. The saint’s bones exude a small but unending supply of dark oil which the monks give to pilgrims. The monastery is full of miracles like this. Fleas, flies, and vermin are unable to enter the monastery. There was once an infestation so bad the monks had to flee, but St. Catherine appeared to them and promised to drive the creatures out, and the monastery has been pest-free ever since. The monks have an endless supply of olive oil for cooking and burning in lamps because once a year a huge flock of birds makes a pilgrimage to the monastery, each one carrying an olive branch in its beak. Each monk has a lamp, and when the abbot dies, the lamp of God’s preferred successor lights on its own. Similarly, when the monastery’s lead priest dies, a scroll appears on the altar before mass. The scroll says which of the brothers should be the new lead priest.

All this suggests a wonderful plot hook: the contravention of miracles. The abbot and lead priest die together in an accident just before the party arrives at the monastery, but no miracles occur to identify their successors. Meanwhile, fleas have returned to the compound and will grow in number as the adventure continues. Worse, soon rats appear. Does this warn of imminent bubonic plague? Investigation reveals the abbot and lead priest were selling the holy olive oil and pocketing the money. The money must be found and given to the poor or God will send plague to kill His monks. If the players are having trouble, this year’s flock of birds arrive early. But instead of an olive branch, each carries a single silver denarius (a Roman silver coin) minted in 33 A.D. This sign recalls the thirty pieces of silver Judas Iscariot was paid to betray Christ. In more fictional settings, you’ll obviously want to use some other evil currency.

Image credit: Wellcome Images. Released under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Libya. The sea is higher than the shore, but does not flow onto the land.

Mauritania. There is a well in this country that is so cold during the day that you can’t drink from it, and so hot at night that you can’t put your hand in it.

Next month, we’ll finish off Sir John Mandeville’s wonders when we push east from the Mediterranean!

Optional Context: The Travels of Sir Johhn Mandeville is a weird book. Obviously, it’s unknowable whether ‘Sir John Mandeville’ is actually the author’s name, whether he was a knight, or even English! And despite some stunning accuracies (and some real howlers), it’s not clear that Mandeville ever actually traveled widely. Almost all the stuff in his book is present in earlier travelogues. If he had a good sense for avoiding other people’s errors, it’s possible Mandeville may have gone no farther than Jerusalem – or even a university library.

Moreover, the book is striking – absolutely stunning – for advocating religious pluralism. This flies in direct opposition to the medieval Church’s teaching that no one gets to heaven except through Roman Catholicism. Mandeville lays out the most accurate overview of Muslim belief available in Europe in the Middle Ages. And he consistently portrays Muslims as more virtuous than European Christians! Mandeville presents many other groups (most notably Brahmans in India) in this way. He also lays out a Biblical argument (mostly grounded in Job) that God loves many people, not just good Christians. In an era of profound religious intolerance, Mandeville stands almost alone in suggesting that the Christian God cares more about how you treat your neighbor than which god you worship.

Honestly, for all that Mandeville is awfully entertaining reading, the book makes more sense as pluralist polemic disguised as a travelogue. Writing a 20-page text in the 14th century about how the Church doesn’t have a monopoly on holiness and most Muslims are good people would be a good way to get hauled before a Church court. But writing a 150-page text about your supposed travels to distant lands and inserting polemic here and there might be an effective way to slip under the radar.

Whatever his motivations, Mandeville proved far more influential than most medieval traveloguers. His book was widely copied and read. Frobisher had a copy with him in 1576 when searching for the Northwest Passage. No less a figure than Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) recommended it as a guidebook to a friend who was leaving for China. And now I debase it as a source of funny stories about snakes and magic wells!

–

Source: The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, translated by C.W.R.D. Mosley (1983, in-depth introduction revised 2005)