The 1904-1909 worker’s strike at a coal mine outside Zeigler, Illinois was the closest thing to open warfare you’re likely to see in a country at peace. American strikes around the turn of the century were notoriously violent, but Zeigler was noteworthy for the military-style tactics both sides used. On one side, you had a billionaire who seemed philanthropic at first, but later showed himself to be a villain. On the other, you had a desperate union that stood to lose everything. There was siege warfare, raids, ambushes, and a spotlight uncomfortably similar to the Eye of Sauron. It’s great RPG material!

Joseph Leiter was a wealthy Chicago businessman born into luxury. He was educated at Harvard, and started in business as a real estate manager, buoyed by a small gift of a million dollars from his father. (That’s $25 million in today’s dollars) When Leiter tried and failed to corner the wheat market, and lost ten million dollars ($250 million today), his family covered the loss. In 1902, he decided to get into coal mining.

For his mine, Leiter bought a lot of land. This will be important soon – normally, businessmen only bought enough property for the mine’s buildings. For the surrounding land, into which the mine’s tunnels would stretch, they just bought the mineral rights. Leiter bought it all. His new mine was the finest for miles around. It was able to produce more coal than any other mine in Illinois, and do it without increasing the number of employees, because Leiter invested in the latest high-performance machinery.

It was not uncommon for large mines to build a ‘company town’ where workers could rent bad houses at inflated prices. Leiter’s company town, Zeigler, was and remains a lovely exception, with wide streets, a circular park at the center, 115 decent-sized homes complete with electricity and running water, weatherproofing, and other amenities that would have been out of place in a normal town, let alone a coal mine’s company town. And all at reasonable rates, too!

So far, this story looks like it’s about to be a big win for compassionate capitalism. But that is not how it developed.

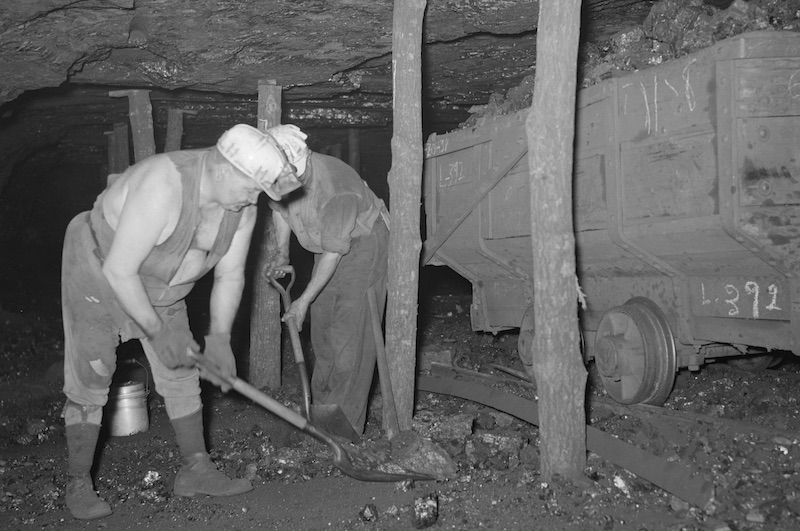

The coal miner’s union, the UMWA, had a strong presence in Illinois. Under UMWA pressure, miners’ wages had quadrupled. The union also dramatically reduced workplace fatalities by forcing the mine companies to institute safety standards. Leiter employed some union miners, but in tasks that required more skill: sinking shafts, grading surfaces, laying tracks, and erecting buildings. For the actual mining work, Leiter employed cheaper non-union labor, and the union hadn’t seemed to notice. But when the first load of coal came out of the Zeigler mine in 1904, the union surprised Leiter with an ultimatum: hire only union labor, and pay everyone the union rate of 56 cents a ton. Leiter refused, arguing that his modern machinery meant that his employees would be able to mine more coal for the same effort, and so would have the same take-home pay at only 38 cents a ton. The union called a strike, and all of Leiter’s miners (including the nonunion labor) walked out.

Both Leiter and the UMWA were products of the violent world of late 19th century strikes, in which scores died in wars of attrition. Both sides knew this dispute would be resolved by blood. If Leiter succeeded in defying the union, the other coal barons of southern Illinois might follow suit. Wages would go into free fall, the mines would stop spending money on safety, workers would start dying in droves again, and their children would go hungry. The union feared that if they lost here, they’d lose everything. The miners were willing to kill to preserve their gains.

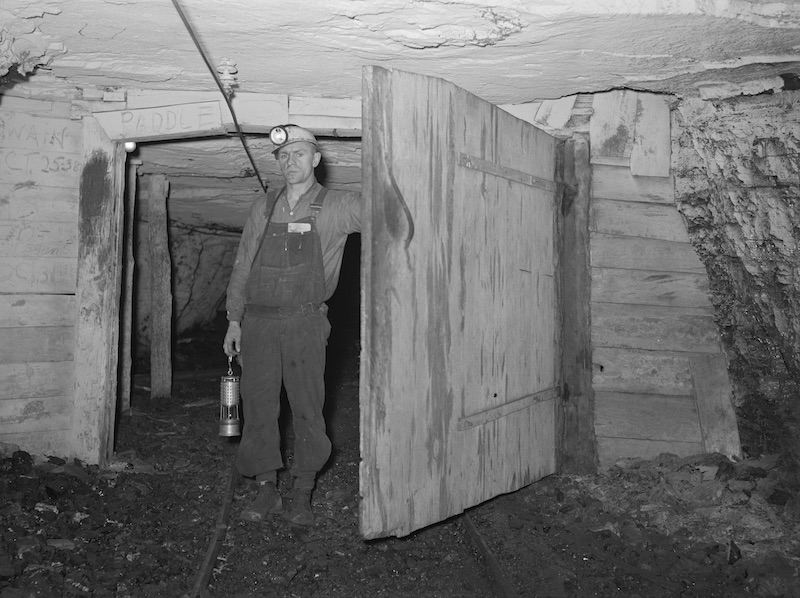

The first day of the strike was July 8th, 1904. By nightfall, Leiter had brought in 42 Pinkerton private guards to patrol his property and issued eviction notices to all striking miners living in Zeigler. He constructed a great fence, enclosing a space 1,500 feet by 400 feet, with stout blockhouses at two of the rectangle’s four corners. The blockhouses were mounted with machine guns, and built to withstand heavy fire. Leiter also placed blockhouses atop the mine office and at the freshwater pumping station on the Big Muddy River, and he placed a huge searchlight atop the mine tipple (a tall building used to load coal cars). Leiter also got an injunction from the district court in Springfield to bar the strikers from entering Zeigler or the mine. Because Leiter owned all the land, he was able to argue that strikers coming onto his land were trespassing, so the strikers were unable to picket. U.S. deputy marshals, their salaries paid by Leiter, joined the Pinkertons defending the Zeigler mine.

Most of the 300 strikers moved into a tent city by the rail junction leading to Zeigler. They surveiled cargo and passengers coming and going by rail from the mine and company town. Leiter imported a labor force, though at great expense. He could only transport them in small numbers to escape the union’s attention, and even then, the passenger cars often came under attack by guns and rocks as they passed through the union camp and sympathetic towns. The strikers launched nightly raids on Zeigler, sneaking through woods and fields to fire on the mine and company houses. Given the conditions, most of Leiter’s workers deserted. He had to keep bringing in train car after train car of disposable labor to replace the men who ran off. Mercifully, all the shooting yielded only one fatality.

The violence ultimately brought the state militia to Zeigler. The whole region resembled a war zone. Pinkertons and marshals patrolled the mine and town. Militiamen set up picket lines in the woods and fields outside Zeigler to try to catch strikers raiding into town. Because Leiter’s legal authority stopped at his property line, his forces couldn’t cross over to the organized and disciplined striker’s camp at the rail junction. Every night, the spotlight atop the mine tipple tracked all across the countryside, looking for raiding parties. And every night there was shooting.

After the arrival of the militia, things slowly started to calm down outside Zeigler. In February of 1905, the militia withdrew. Nonetheless, Leiter’s workers continued to desert. And then, on April 3rd, the beginning of the end came for Leiter and his strikebreakers.

A huge explosion rocked the Zeigler mine. Smoke billowed from the air shafts, and debris hurled up the shaft rained across the land around. 48 miners died. Leiter claimed the union did it, but three independent investigations found otherwise. Coal faces naturally exude methane, so coal mines must be kept ventilated. The ventilation shafts in the Zeigler mine were broken, permitting methane to build up in dangerous quantities, while introducing just enough oxygen for an explosion. Simultaneously, the company had been storing its blasting powder in the mine for convenience, which made the explosion much worse. All this was a shocking breach of standard mine safety procedures, and were examples of precisely the sorts of practices the union fought against.

Three months later, Leiter had recruited a new labor force and re-opened the mine. By this point, the strike was a year old. The strikers moved out of their camp and found other work. The strike was technically still in effect, but Leiter had effectively won. Then a fire started in the Zeigler mine in November, 1908. On January 10th, 1909, there was another explosion, caused by the company’s unsafe response to the fire. On February 9th, 1909, there was a third explosion with the same cause. 93 of Leiter’s employees had died in his mine by this point. Leiter sold the mine.

A new company took over the Zeigler site. Every worker they hired carried a union card. The union had won.

There’s an important postscript to this story. Why did Leiter leave coal mining? Was it because he finally had a pang of conscience over killing his employees by the truckload?

Don’t be ridiculous.

Leiter’s mother grew worried that her son would be killed in an accident in his mine, and used financial chicanery to force him to quit. Note that she also didn’t care about the dead miners. The men who marched into Hades every day to keep her in a posh lifestyle – and often didn’t march out – merited not a thought. It was only the life of her darling son that mattered. This attitude is vital to understanding the rise of unions around the turn of the century.

At your table, basing an adventure on the Zeigler strike is a great way to set up a wildly unusual siege/raid scenario. Skirmishing and siege warfare are always a lot of fun, but I’ll wager you’ve never done it against a backdrop of a union labor dispute. Plus, the Eye-of-Sauron-like spotlight and the defenders being limited to Joseph Leiter’s property present novel tactical wrinkles that will help a scenario based on this one feel fresh and different.

Your PCs could be hired by the UMWA to win the strike, or by Leiter to break it. Clever PCs might start a bidding war for their services. Both sides had deep pockets, but in 1904, Leiter’s were deeper.

Whichever side the PCs are on, infiltrating the enemy is a sound tactic and fun roleplay. If you can get the folks on the other side to turn on each other, they’ll collapse and you’ll win. Strikebreaking PCs need to undermine the solidarity that keeps the union strong. With Leiter’s permission, they may offer bonuses to the first 20% of strikers to cross the picket lines and return to work – but threaten that the last 20% of strikers to try to return to work will not be re-hired.

PCs backing the union can do something similar by infiltrating the mine and talking to the strikebreakers. The union’s raids are putting the strikebreakers under a lot of pressure, and disrupting the strikebreakers’ unity will get even more of them to defect. The PCs might want to find the natural divisions among the workers, and exploit them. Perhaps there’s a mutual mistrust between the professional strikebreakers (who’ve worked for many such shops) and the folks who are just poor and desperate enough to agree to take this job. The PCs might spread rumors that the poor are secret union sympathizers letting union fighters stay in their homes to murder the professional strikebreakers while they sleep. You might also have some luck starting a rumor that the professional strikebreakers are trying to cause mine accidents to kill the poor folks and get a bigger cut of the paycheck.

Finally, you can use ethical questions around mine safety to kick your adventure up a notch. Strikebreaking PCs will see the powder stored in the mine, and the bad ventilation permitting methane buildup. Tell them Leiter is aware of these safety dangers and doesn’t care. Do the PCs have a moral responsibility to go public, selling out their employer but keeping the strikebreaking miners alive? Strike-breaking PCs who infiltrate the mine will see the same thing, but from the opposite direction. Mine explosions are expensive, and will hurt Leiter’s business interests. Do they keep their mouths shut, sacrificing the lives of strikebreaking miners to help the cause of the strike? Or do they notify the non-union foreman, who may be too inexperienced to recognize the safety problems?