Castles are a must-have for any traditional fantasy campaign. They’re great fun to infiltrate, they lend ambience to everything, and when fallen into ruin, they make terrific dungeons. Unfortunately, castles in RPGs can wind up feeling a little generic. Here, then, are three real (and real cool!) British castles to shake up your citadel game!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

Portchester Castle

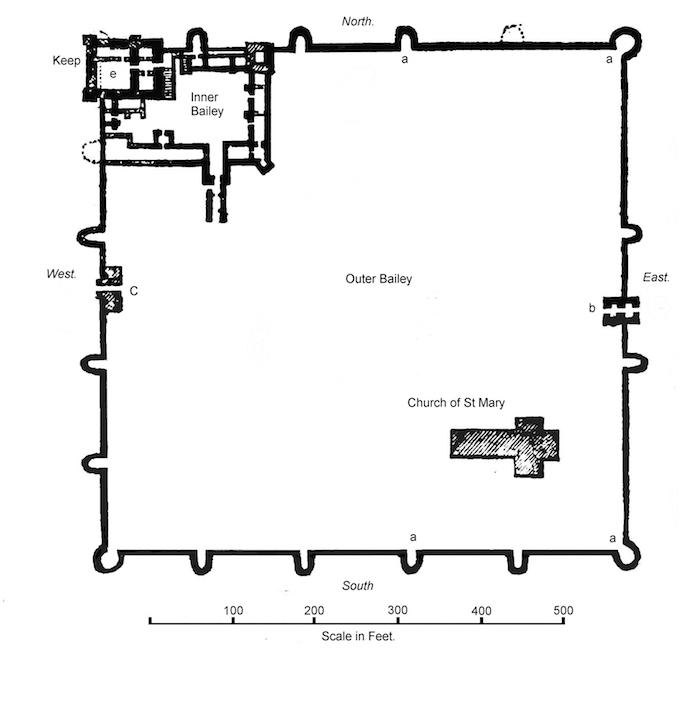

Portchester Castle surveys the harbor at Portsmouth, one of the best ports in England. Its strategic location means the site has been fortified for almost two millennia. The modern site is a series of squares within squares, all sharing the same northwest corner.

The outermost square was built by the Romans in the 3rd century A.D. The walls are six meters high, two hundred meters on a side, and enclose ten acres. They’re arguably the best-preserved Roman fortifications in Britain; even many of the towers are original Roman construction! This fort was part of a larger defensive work: the Saxon Shore. The Romans built a series of strongholds along the coastlines on both sides of the English Channel to deter sea-going raids and migration from the tribes of Germany. Ironically, the forts kept out of England the very people most Englishmen now see as their ancestors: the Jutes, Angles, and Saxons. Once the Romans withdrew from Britain, these Germanic tribes quickly moved in, and the fortifications at Portchester became a Saxon settlement.

After the Normans conquered England in the 11th century, the new French-speaking ruling class embarked on a spate of castle-building to keep the restive Saxon locals cowed. Portchester was a natural choice for a castle; building within the Roman walls saved time and money. In fits and starts over about 100 years, something recognizable as the current Portchester Castle took shape.

Image credit: geni. Released under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

The keep is in the fort’s northwest corner, sharing the wall with the Roman fort. Its base is seventeen meters by seventeen meters, and it’s thirty meters high. The keep is striking in its simplicity: sheer walls, no towers, barely any buttressing. It looks like two children’s blocks stacked on top of each other. This austere style was standard for the Norman era. European castle-building and siegecraft were still in their early stages.

Beyond the keep is a wall enclosing an inner bailey (or courtyard) occupying the rest of the northwestern quarter of the old fort. Stone buildings in the inner bailey fulfilled household functions, like kitchens and halls. The rest of the old fort was now the outer bailey of the castle. From 1128 to 1150, there was a priory in the outer bailey. When the clergy moved, the castle’s lord pulled down all their buildings except the church (which still stands). Weirdly, the village of Portchester grew up outside the old fort, while all that fortified open space in the outer bailey was used as farmland.

Image credit: Charles Miller. Released under a CC BY 2.0 license

In your campaign, a fictional castle based on Portchester would be the perfect size for a base of operations for the party. It’s also distinctive! With its austere keep, seaside location, and use by a series of different nations, your players will feel like the castle is uniquely ‘theirs’, not some generic whatever. Consider offering them the castle as a grant in reward for service. To give them even more buy-in, have the keep be abandoned and occupied by monsters or brigands. The local duke says the PCs can have the castle – if they can clear it out first! Turning the castle into a short dungeon crawl has the added advantage of spending a session with the players focused closely on the castle’s layout, in the form of a dungeon map. That way, when they take it over, they have concrete knowledge of their stronghold, making it feel more ‘real’.

Chepstow Castle

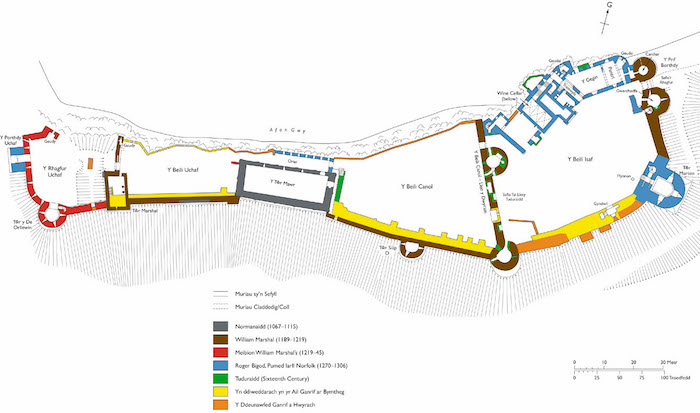

Chepstow Castle was another Norman citadel, this one built for a much more urgent purpose: securing the border with Wales. When the Normans conquered England, they did not take Wales, leaving a vulnerable border open to the west. Chepstow sits atop high bluffs overlooking a critical crossing of the River Wye, the limit of Norman control. Construction began only a year after the Norman invasion, and Chepstow was the only castle from this immediate rush to have been built initially of stone, rather than wood.

Because it’s built on a narrow stretch of cliffs, Chepostow has a strange layout: a series of four baileys built one after another over about two hundred years. The Great Tower (in gray, above), a rectangular keep, was built quickly, but after that, the marcher lords that controlled Chepstow just lengthened the castle along the cliffs when they felt like it, adding another bailey when their household of retainers and servants grew too large to fit in the existing stronghold. Between these periodic updates and Chepstow’s strategic location, the castle remained militarily relevant for a peculiarly long time. It was adapted for defense by cannon and musket, and was an important front line in the English Civil War of 1642-1651. Today, the site is largely crumbling and tumbledown.

It’s Chepstow’s peculiar layout that makes it useful at the gaming table. It’s mostly linear, with some opportunities for detours – which makes it the perfect layout for a dungeon. The four baileys give room for memorable, setpiece-style combats, while the towers and stone buildings provide opportunities for puzzles and places to put dungeon-appropriate NPCs like water weirds and ghosts. Chepstow is small enough that you’ll probably want to stock the baileys with unintelligent monsters, so it’s not weird that a fight in the first bailey doesn’t attract every combatant in baileys two through four.

Claypotts Tower

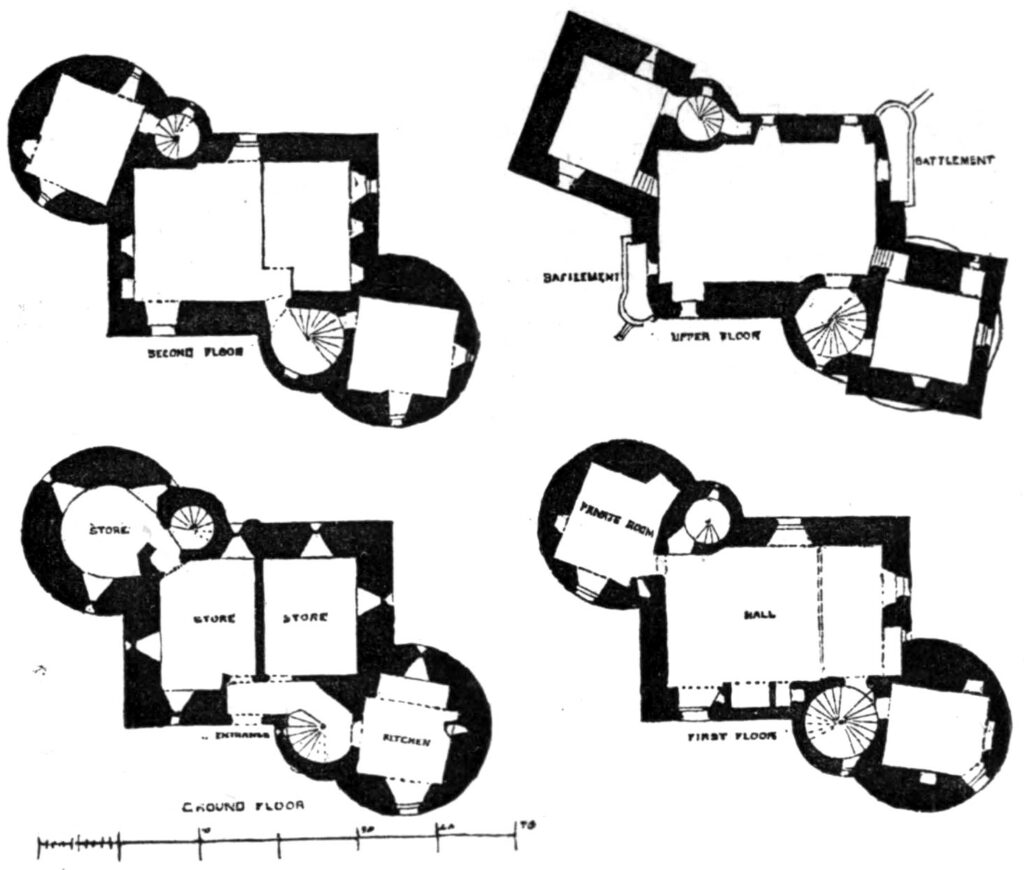

For our final ‘castle’, we move north to Scotland. 1300 to 1600 saw the proliferation of an unusual style of fortification called the ’tower house’ or ‘peel’. Too small to be a proper keep, a tower house was the home of a clan chief, small lord, or wealthy farmer, built as a single, stout-walled tower. It wasn’t intended to serve as a base for troops or to survive a siege. Instead, it was a comfortable enough home for a local notable and his family that could also shelter their tenant farmers overnight when the neighbors came raiding. A few gunports ensured the raiders gave the tower a wide berth while they were rustling cattle and sheep. The peel is a response to the peculiar security situation in this period of Scottish and border history.

Claypotts Tower, outside Dundee, was built between 1569 and 1588. A central, square, four-story house has two large round towers protruding from the southwest and northeast corners. The round towers become square for their top story, since square rooms are much more convenient to live in, but it gives the house an odd appearance. The door is stout and easy to barricade. The ground-floor windows are too small to crawl through, but large enough to shoot through.

Claypotts was built by a John Strachan, who was a wealthy tenant farmer of a nearby abbey. In 1560, the Scottish parliament outlawed Catholicism. Since the abbey no longer had any legal rights, John Strachan took over the land he had been leasing, and soon began construction of Claypotts.

Claypotts Tower is probably too small to make a fun dungeon, but what it does offer is the possibility of a small, personal-scale siege. In your campaign, if someone is holed up inside a fictional version of Claypotts Tower, your players could have a lot of fun getting them out! The tower’s thick stone walls and commanding gunports make it a tough nut to crack. The PCs might have to use subterfuge, manipulation, or a clever scheme to get at their target.