Valladolid is a city on the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico. In the 1840s, it was a remarkable town: remote, hollow, cruel, and left behind by the passage of time. It was also a town whose days were numbered. A town based on Valladolid at its most extreme, in the years before its reckoning, is an amazing adventure site.

In the 1840s, the Yucatan peninsula was so remote it was almost a separate country. A small criollo (white, Spanish-descended) overclass ruled the far larger populations of Maya natives and mestizos (people of mixed native and white heritage). The Maya and (to a lesser extent) mestizos endured endless abuses from their criollo masters: debt peonage, land theft, and whippings. The criollos fought civil wars amongst themselves over changes to the Yucatecan state constitution. Affairs in Mexico City had little impact on the Yucatan, where life continued very much as it had for 300 years since the conquistadors seized these lands.

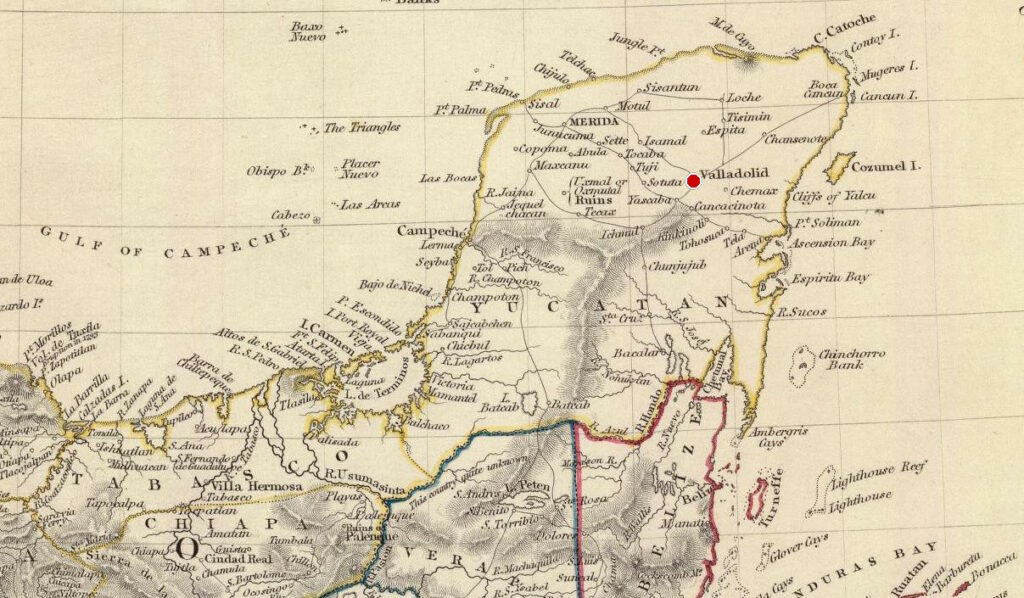

Valladolid was like the rest of the Yucatan, but more so. In importance, it ranked behind the dusty capital of Mérida, the fading port of Campeche, and the small-but-growing port of Sisal. Landlocked Valladolid was a distant fourth: a remote and forgotten corner of a remote and forgotten region.

Valladolid was a criollo town. Maya and mestizos were not permitted in the city center. Mansions decorated with Castlian coats of arms squatted along the town’s main roads, but many of them were abandoned, roofs caved in decades ago. Business stagnated in the town, for its most prominent citizens clung to the aristocratic belief that actual work (except cattle ranching) is beneath a gentleman. There was for a time a cotton mill in Valladolid, but it went silent after the death of its founder. The town had neither school, nor doctor, nor druggist, nor mason.

Valladolid’s fifteen thousand citizens were proud of their isolated refuge and called the town “The Sultaness of the East”. The East, in this case, is the eastern Yucatan. It earned the title purely on the grounds that there was nothing else larger than a village on that side of the peninsula.

In other parts of the Yucatan, the old class privileges were starting to fade. The criollos were terrified that if they loosened their grip, their whole system would fall apart. So the whippings grew more frequent and more severe. Landholders raised their rents, priests raised their fees, and the government raised its taxes. More and more Maya slid into debt peonage. Cattle ranchers ‘misplaced’ Maya deeds and confiscated communal land. They refused to corral their cattle, so the Maya had to construct their own fences to protect their cornfields. Yet there were seven Maya to every criollo or mestizo in Valladolid district, the highest ratio in the Yucatan. The criollos’ position was unsustainable and it would all fall apart shortly.

The Yucatan suffered frequent civil wars as criollo fought criollo over which politician – to us, utterly interchangeable – should rule the state. In some of these civil wars, the colonels armed the Maya to fight on their side. This finally came to a head in 1847. The latest Yucatecan civil war was over whether the state should send troops to help the Mexican federal government in the Mexican-American War. The anti-Mexican (pro-neutrality) side armed the Maya and marched on Valladolid. On their own initiative, without consulting their criollo officers, they set a careful ambush, routed the pro-Mexican troops, and entered the city.

With rifles in their hands in the hated city center of Valladolid, the Maya rioted. They dragged an aristocrat into the street and hacked him apart with machetes. They did the same to a priest in his hammock. Some criollos they raped. Others they tied spread-eagle to windows to stab and mutilate. Cries rang through the streets: “Kill all those who have shirts!”

The sack lasted three days. Most of the townsfolk survived, either by fleeing or hiding. But the Maya weren’t going back to servitude. The sack of Valladolid was one of the precipitating incidents of the Caste War, a Maya-criollo race war (with mestizos on both sides) that raged across the eastern Yucatan for over fifty years. Both sides tried to genocide the other. In the first three years alone, almost forty percent of the population of the Yucatan (Maya and criollo alike) was killed. The population of Valladolid district dropped by seventy-five percent. The Caste War had no victors.

A fictionalized version of Valladolid just before the revolt makes an amazing adventure site. The simmering tension, the isolation, the hollowed-out economy, the delusions of grandeur – it’s all a pot about to boil over. In an empty, cruel setting like Valladolid, will the PCs do what they can to keep peace? Or will they allow the whole rotten system to burn, knowing the resulting carnage will probably be worse than the status quo?

Adventure hooks in 1840s Valladolid

– A new breed of cattle pushes through any fence the Maya can make. Is there anything the PCs can do to intercede on the natives’ behalf?

– A popular Maya curandero is widely known to be sheltering someone guilty of defrauding a mestizo overseer out of the his tax due. The overseer just found out, and he’s heading to the shaman’s house with a whip. He’s lashed men to death in the past. If he kills the guilty party, there’s a risk the respected curandero may get drawn in and the violence may spread. What do the PCs do?

– Some recently-whipped Maya malcontents have vanished, last seen bound for British Honduras (Belize), where they will be able to purchase weapons if they want them. Their plan is to return in time for Carnival and enter the city while masked. Can the PCs learn this and catch them? Do they really want to?

– The town’s leaders are sending representatives to a conference to overhaul the state’s tax system. The efforts will be meaningless unless someone (perhaps the PCs?) can convince these criollo notables to address the rot at the root of the Yucatan: rights determined by caste, and the unceasing expropriation of Maya-owned land.

– Reliable water for agriculture is precious in the Yucatan. A criollo rancher is trying to take over a cenote (natural well) owned by a Maya village so he can expand his operations. The village is contesting his actions in court, not that anyone expects a fair verdict. But when the village headman arrives in court, he finds the deed – issued decades ago by the former imperial Spanish governor – has vanished from his person. In truth, the deed being held by the rancher’s majordomo, who pickpocketed it from the headman when he stopped in a bar along the way. To learn this, the PCs will have to retrace the headman’s steps and interview potential suspects and eyewitnesses, all of whom have a dog in this fight.

Next week, we’ll dig into the awful mess of the Caste War itself and pick out a few highly gameable details!

Source: The Caste War of Yucatan by Nelson Reed (1964)