Monsters aren’t just for fighting! They’re also for roleplaying with, puzzling out, and adding color to your campaign. Back in 2019, I wrote a post about four weird historical monsters from medieval Europe. This is a long-delayed sequel, with four monsters (yokai) from four different periods of Japanese history: one beneficial, one villainous, one morally gray, and one annoyingly mischievous.

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Arthur Brown – who also helped with translation for this week’s post. Thanks for helping keep the lights on and the block prints properly selected! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Arthur, head over to Patreon page – and thank you!

The Good

The ningyo is a woman-fish hybrid, a sort of Japanese mermaid. Sighting a ningyo could be good or bad, but I’m particularly intrigued by a woodblock print from 1805 (above). It shows a ningyo and assures the reader that anyone who looks at the “fish” even once will have a long and happy life, free of calamities and natural disasters.

From an RPG perspective, the ningyo’s beneficence is neat, but what’s really cool is the NPCs it generates. A person who has seen a ningyo is presumably valuable as a ward against natural disasters. Imagine two fishing villages. The first has a ningyo living in its harbor. Many people have seen her. No typhoons, tsunamis, fires, etc. have struck the village in living memory, because so many of the residents are protected against such things, and you can hardly have a selective tsunami. The other village lies on a long, open bay with no protection against winds from the sea. The fishing is good, but even the smallest typhoon drives water right up the bay. Storm surge demolishes all buildings in the town every few years.

If the PCs can convince even one person from the first village who’s seen a ningyo to move to the second village, it will do so much good! The headman of the second village may commission them to do just that. But it’s a hard sell. The transplant can never leave their new village. Not only will the second village be unprotected in their absence, travel is dangerous. They might fall ill, suffer an accident, or be robbed. If they die while traveling, all is for naught. They can’t even go home to attend a funeral. The PCs will have to get to know the few people in the first village who are even remotely interested in uprooting, then figure out what will sweeten the pot enough to get them to agree to leave behind everything they know – permanently.

The Bad

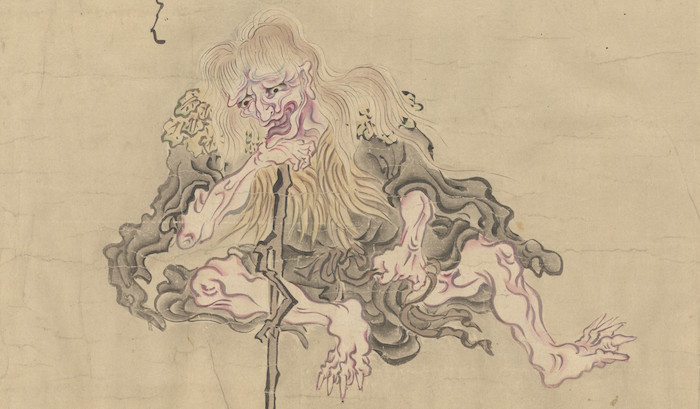

Oni are hideous ogre/demon monsters common in Japanese pop culture. We are interested in one oni tale in particular from the 1222 text A Companion in Solitude. The story is particularly noteworthy for being about a female oni.

A young woman in Mino Province had a lover who lived far away and neglected her. She took to her bed and stopped eating. One day, she tied her hair in knots and smeared them with millet jelly so they resembled the horns of an oni. She put on a red skirt and ran off to hunt down her faithless lover. But after she murdered him, she found her false horns had become real. By behaving like an oni in oni form, she had become one in truth! Driven by pain and resentment, she rampaged across the countryside for thirty years until some brave villagers set fire to the temple she was hiding in. The oni-woman burst from the flames, told the peasants her story, and leapt back into the fire to die. Related stories appear in texts and plays from the 1300s and the 1400s.

A story like this one can lend pathos to any humanoid monster. “She wasn’t always bad” is a staple for a reason. Make sure the reason your monster put on a monstrous costume matches the wicked themes the monster is meant to evoke. For example, if you’re doing this with one of D&D’s cannibal gnolls, maybe the NPC put on a hyena pelt to waylay travelers and eat them during a famine. The NPC’s actions are still abhorrent, but now they’re understandable. Make your players wrestle with the question of whether such a creature is redeemable!

The Ugly

The yamamba is a wild woman of the woods. In some stories, she’s demonic. She kills anyone who intrudes upon her mountain home, and even comes down into the villages to terrorize people. In other stories, she’s sympathetic. She’s survived great hardship by her resourcefulness and physical strength. In these stories, trespassing in the yamamba’s forest brings misfortune, but if you are polite when she descends into the village, she’ll help you.

A set of beliefs collected in Gifu Prefecture during the mid-1900s center around a particular yamamba. She kept one eye closed, had no nose, a big mouth, and no teeth. She lived in the mountains eating birds and animals. Her hair was full of centipedes and caterpillars. When she was in a foul mood, the mountainside shook with her fury, but when she was happy, she’d come help the farmers with their chores. The farmers were grateful, since she was so strong she did as much work as any five men. Every December, she’d buy sake in the market before retreating up the mountain for the winter. When she died, the villagers buried her at the base of a rock that eroded into the shape of her hideous face.

I’m not sure why, but I found this particular yamamba arresting. Something about the story grabbed hold of me, and I can’t get it out of my head. At your table, an NPC based on this yamamba might confront PCs she catches in her woods. If they don’t attack, but rather hear out her reasonable requests (don’t chop down any trees, only use fallen wood for fires, leave no trace), they’ll probably find her a font of valuable information about their wilderness destination.

The Bizarre

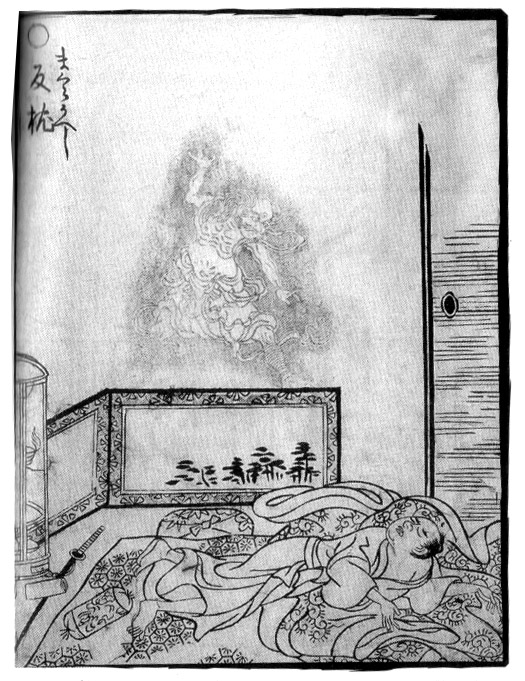

Monsters, especially Japanese ones, are frequently liminal. They haunt in-between places and times, like bridges, seashores, the edges of towns, and twilight. A fabulous example is the makura-gaeshi, the ‘pillow-shifter’. This monster was well-known in the 1700s. Have you ever woken up in the morning and wondered how your pillow got turned upside-down or moved way over there? That’s the work of the makura-gaeshi, a specter that comes to you as you sleep to rearrange your pillow!

This is bizarre, but realize: the pillow is the threshold to sleep. It’s a kind of magical device through which you travel to another world. Consequently, Edo-era Japan had a taboo against kicking or throwing pillows around. This is connected to the idea that in sleep, the spirit leaves your physical body. By moving your pillow around (especially to the north, the direction of death), the makura-gaeshi makes it harder for your spirit to come home to your body. Maybe you’ll sleep too long. Maybe you’ll never wake up at all.

Unless your sessions are about two hours long, this little guy probably isn’t an adventure unto himself. But he’s a great complication! In the midst of whatever other nonsense you’ve got going on, this little specter is making people sleep late – sometimes very late – and always at the worst possible time. The consequences should complicate and bedevil the PCs. Can they figure out what’s happening before someone fails to wake up for good?

–

Sources:

The Book of Yokai by Michael Dylan Foster (2015)

Arthur Brown, personal correspondence