An 1880s joint expedition to map the border between Russia and Iran provides an amazing template for a surveying adventure. “Surveying?” you say. “How dull!” But hear me out! This joint expedition is full of smuggling, religious confrontations, international incidents, small-scale domestic politics, pride, feuds, and maybe even a secret villain operating from the shadows. Seriously, it’s an amazing template for an adventure where your party helps redraw a border. Your PCs could be hired on as translators, security guards, surveyors, or diplomats, and they will absolutely have their work cut out for them. Let’s take a look!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

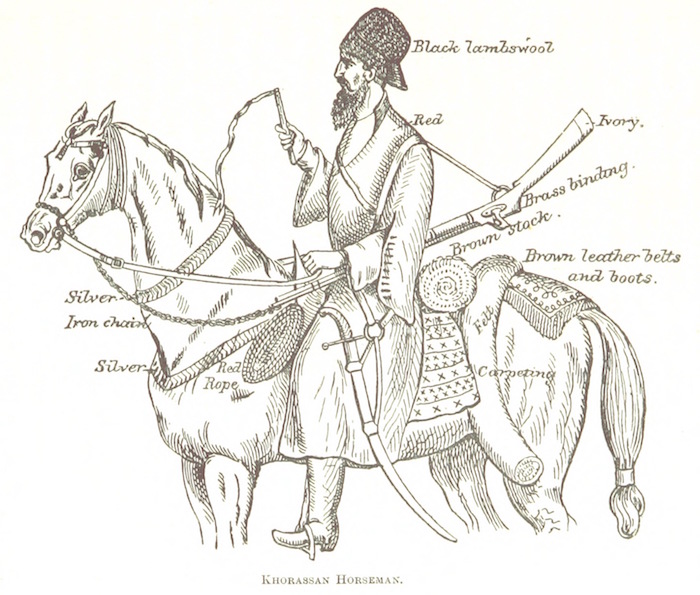

The historical region of Khorasan falls in what is today northeastern Iran, western Afghanistan, and most of Turkmenistan. In the early 1800s, Khorasan was nominally a part of the empire called ‘Persia’ by the west and ‘Iran’ by its residents. But Khorasan was a wild and distant place, far from the seat of power in Tehran. The Shah (the Iranian emperor) exerted little control over it. In 1881, the Russian Empire conquered the Turkmen of northern Khorasan. This was an invasion of Iranian territory (sort of), but the Iranian military was a joke and there was nothing the Shah could do. So Iran and Russia signed a treaty granting Russia northern Khorasan and establishing a joint Russo-Iranian expedition to map the new border. It would be a wild trip.

My source for this post is the memoirs of Aqa Reza, the Iranian translator on the joint expedition. He was the son of an unimportant cloth merchant, but he had a knack for picking up languages and being in the right place at the right time. These habits propelled him on an unexpected, meteoric rise through the Iranian foreign service that culminated in him being appointed a non-hereditary prince of the Qajar dynasty. At the time of this delegation, our surprise wunderkind was thirty years old and had already attracted the notice of the Shah. His memoirs are probably a bit embellished, but the broad strokes seem reliable. Reza consistently uses ‘Iran’ instead of ‘Persia’, so I am doing the same.

Reza wasn’t sure he wanted to be on this border expedition. He had a cushy job as a secretary in Tblisi, a city fought over by Russia and Iran that was presently in Russian hands. (Today, Tblisi is the capital of the nation of Georgia.) Khorasan, he’d heard, was an empty quarter full of nothing but scorpions and tarantulas. But he’d been handpicked by the Shah for this assignment, so off he went. He had to cross the Caspian Sea to reach Tehran, pick up his orders, then go overland to Mashhad to meet the rest of the Iranian delegation. Roads were bad in Iran and there were no railroads, so this was no small journey.

He crossed the Caspain by ship from Baku (then under Russian control, today in Azerbaijan) to Bandar Anzali, Iran. He was worried about finding the way from Bandar Anzali to Tehran, but luckily bumped into a young Iranian merchant named Mohammad Hossein in Baku who offered to show him the way. Hossein upheld his side of the bargain, but also took advantage of it. He was traveling with several sealed crates of merchandise. Hossein showed the customs officials letters from the consulate in Baku indicating he was traveling with Reza, a member of the foreign service, and convinced both the Russian and Iranian customs officials that his crates were official diplomatic business and could not be inspected. If you use an NPC based on Hossein as a guide at your table, those crates should definitely contain something worth investigating. Weapons are an obvious choice. If the PCs report your Hossein-analogue for exceeding his (nonexistent) authority, they’ll lose a helpful guide. But if they don’t report him, those familiar crates should pop up again later in the adventure to bedevil the party. Maybe the PCs are attacked by some unusually well-armed bandits and find the crates in their camp.

From Tehran, it was on to Mashhad, in far northeastern Iran. Mashhad is home to the burial site of the eighth Shia Imam. It’s one of the holiest sites in Shiism, the chief form of Islam in Iran. Reza was a good Iranian Muslim, so naturally took a day to visit the shrine. Unfortunately, he was gross and hairy from all his time on the road and two religious students at the shrine thought he was Armenian (apologies to any Armenians in the audience). Armenians are mostly Christians, and thus are forbidden at the shrine. These two students raised such a big stink it looked like Reza wasn’t going to be able to get into the shrine. So he turned it around on the students. He started quizzing them on fine points of doctrine, especially on predestination and free will as it related to particular religious injunctions. Embarrassed, they withdrew. At your table, a stink modeled on these jerks can be a fun little scene. It’ll give any players who are really into roleplay an excuse to get irate and loud. You don’t want to linger on a scene like this, but it’s a fun little piece of punctuation.

Outside Mashhad, Reza met up with the rest of the Iranian delegation. Much to Reza’s surprise, they didn’t then head for the border. Instead, they met up with an infantry brigade, three regional governors, and tribal cavalry. Supposedly, a sayyid (a descendant of Muhammad, Fatimah, and Ali – the holiest bloodline in Shia Islam) was raising an army for a revolt. The Iranian delegation to the border expedition was ordered to help the regional governors put down the revolt. A few years back, Reza had performed certain services and been rewarded with a military officer’s uniform and the right to wear it. He’d been wearing the uniform on the trip, so folks thought he knew a thing or two about leading soldiers. In truth, his expertise in warfare extended about as far as rifle shooting. Nonetheless, he was given command of 200 cavalry and ordered to secure such-and-such a place.

They rode several days and reached the place, which overlooked a dry plain. And there on the plain was a great cloud of dust – riders! Surely this was the sayyid and his 5,000 Turkmen horsemen. Reza’s 200 cavalry would be slaughtered! The cavalry asked permission to flee, but Reza pointed out that their horses were tired. They’d never escape. So, with much grumbling, the cavalry reluctantly piled up stones to make defenses. Eventually, the dust cloud grew near enough that everyone could see it was no army. It was a caravan of 300 camels laden with flour and their Russian cossack escort. The caravaners saw the Iranians hiding behind their stones and came over to ask why they were behaving so strangely. Reza told them about the black-veiled sayyid claiming to be the return of the last Imam and the harbinger of the end of days. The caravaners laughed and laughed. They’d once heard about a rebel leader with a handful of followers, sure. But Russians patrolled this territory now, and the Russian Army had no patience for such nonsense. The black-veiled sayyid had been dealt with long before he could amass 5,000 followers.

Then Reza’s 200 cavalry put him in an uncomfortable predicament.They insisted Reza treat this as a great victory, that he write a letter talking about how they’d defeated the sayyid and his army. They assured their unqualified commander that this was how things were done way out here, so far from Tehran. If you wanted something, you lied about winning a victory and demanded a reward from the government. “It isn’t our fault the sayyid doesn’t have an army, or if he does, that he didn’t appear. He should have, and then we would have beaten him. So sign this letter saying we did.” Reza protested, but his troops explained that if he didn’t sign the letter, their translator ‘commander’ could find his own way back to the delegation, and that he might not survive the trip. Reza caved. He signed the letter. He and his temporary troops were later sent money for their bravery. Since the sayyid had clearly been dealt with, the regional governors went home. The senior officers of the gathered force received even more money and were issued jeweled swords.

At your table, this situation could fill an entire short session. An emergency forces some authority figure to put the unqualified party in command of a small force of cowardly, lying soldiers. Everyone thinks they’re about to meet the enemy, then are roundly mocked by observers when that doesn’t happen. Then those same soldiers try to blackmail the party. You might be tempted to resolve that last bit with a single roll to determine if the soldiers can be brought to heel. Instead, let it play out. Let the PCs really sweat in this sticky, uncomfortable situation where all their options are bad.

The Iranian delegation finally met the Russian delegation at the town of Lotfabad. Today, it’s on the Iranian-Turkmenistani border, but at the time it was on the Iranian-Russian border. Between Lotfabad and the Caspian Sea, maps were good enough that distant diplomats had already determined where the new border lay. East of Lotfabad the maps were bad enough that determining the border required the joint expedition.

When the Iranian delegation reached Lotfabad, they found the boundary line that distant diplomats had agreed to actually ran through the fields of the city. If this boundary were instituted, this Iranian city would be cut off from farmland belonging to 500 Iranian families – farmland the city needed to feed itself. The head of the Iranian delegation, Soleiman Khan Saheb-e Ekhtiyar, begged his Russian counterpart, Colonel Karavaev, to agree to move the border just a hair and keep the city from starving. But the colonel had orders from St. Petersburg not to budge. Russia held the upper hand and their foreign ministry forbade Karavaev from yielding out of mercy or justice. Ekhtiyar exploded, insulted the colonel, and stormed out. He telegraphed the Shah to offer his resignation. The Shah refused it and ordered him to give the Russians what they wanted. Avoiding a war Iran would lose was worth hurting the people of Lotfabad. But Ekhtiyar had given his word to the people of Lotfabad that he wouldn’t abandon them. What was he to do?

The only avenue left was diplomatic backchannels. And here, Reza could help. The Russian commander-in-chief of the armies in the newly-conquered territory was one General Komarov. He’d earlier been stationed in Tblisi, where Reza had befriended him, his wife, and his daughters. So Reza, with Ekhtiyar’s permission, left the delegation to ride several days to Ashgabat, where General Komarov was headquartered. The Komarov family was surprised to see Reza, but welcomed him as a friend. Reza explained the situation to Komarov, who already knew about it but had no reason to care – until the request came from a family friend. Komarov pulled some levers in the Russian General Staff, and three days later the Russian delegation to the boundary expedition received new orders.

This meant the personal honor of Ekhtiyar, the head of the Iranian delegation, was secure. In gratitude, Ekhtiyar promised to obtain a senior title and appropriate salary from the Shah for Reza. He also took Reza on as a protege, a relationship they maintained for decades.

Reza’s next task was to negotiate the equitable division of water from the nearby river into two channels. One would go south to Lotfabad, the other north to the Turkmen forts. Reza thought he did well at this until he was summoned to Ekhtiyar’s tent by two Iranian soldiers and a letter from Ekhtiyar that began, “Sir, I regret that I considered you a Muslim and a patriot. I now see that I made a mistake.” The soldiers worked for Ekhtiyar and were part of the only competent unit in the entire Iranian military: a cavalry unit trained in the Russian cossack model. There was no getting away or bribing them.

On arriving at Ekhtiyar’s tent, Reza learned that the headmen of Lotfabad sent a letter saying that the new channel was intentionally flawed so Lotfabad would get no water, while the Turkmen across the new border would get all of it. Reza exploded. He’d been arrested and humiliated for no reason. The new channel was fine, as a quick investigation confirmed. Hadn’t Reza earned a little trust? Ekhtiyar apologized. But the real question was why the headmen of Lotfabad had done this.

Reza interrogated the headmen. It turned out none of them understood what a translator was, nor could Reza make them understand. They told him things, then watched as he turned around and told the Russian delegation things in a language they didn’t understand. Clearly he was betraying them to the Russians, right? Followup questioning revealed that someone had been manipulating the headmen’s ignorance to turn them against Reza. They were reticent to identify this person, though, and they really did seem contrite, so out of politeness Reza let the matter drop.

This won’t be the last time it seems like there may be someone working in the shadows to scuttle Reza’s rising star. In real history, I’m sure it’s a coincidence. Probably there was some local cleric who misunderstood what was happening in Lotfabad and tried to conspire against Reza. And every time someone worked against Reza in the rest of this story, it was a separate misunderstanding involving separate people. But at your table, this business with the headmen in your fictionalized Lotfabad-analogue may be the first act of this adventure’s villain. The villain might be a member of the Russian-analogue delegation trying to sow dissent among her counterparts. It might be someone from a PC’s backstory. It might even be the black-veiled sayyid for some reason. The nature of the villain isn’t actually very important, as long as they have a good reason to hate the party and hide their face.

The expedition lasted four years (1883-1887). Reza had many adventures in that time. He met a faqir (in this context, a Sufi Muslim hermit) who could see far-off places. He visited a village of centenarians. He met a Kurdish chief who needed to have all his teeth pulled and replaced with false teeth, but wasn’t sure he’d be able to eat with false teeth. So he had all his manservant’s teeth pulled out to see if he could eat after the operation! Once, a mysterious someone convinced a regional governor to withhold the Iranian delegation’s salaries, and Reza had to pawn his possessions to buy food. He managed to save the delegation (supposedly) by writing an apropos piece of poetry and sending it to the governor.

Twice, the Iranian delegation spent the winter south of the border in Quchan. Once, he ran afoul of Quchan’s Friday imam: the pastor of the largest and most important mosque in town. A mysterious someone told the Friday imam about a treatise Reza once wrote about how to write Farsi, the primary Iranian language, using the Latin (European) alphabet. Reza found the Latin alphabet more convenient than the Persian one and felt changing scripts would help Iran integrate better with Europe. But the mysterious someone misrepresented Reza’s treatise as being about how to write Arabic with Latin letters. This is tricky, because several Arabic sounds are not represented in the Latin alphabet. And since the Quran is in Arabic, and the words of the Quran were composed in Arabic by God himself, transliterating (not even translating) the Quran into European letters would mean altering God’s literal words. The Friday imam issued a decree that Reza should be killed.

How was Reza going to get himself out of this pickle? If he could only explain himself to the imam, everything would be fine. But the imam’s people would kill Reza before he could reach him! Instead, Reza wrote a letter to the imam pretending to be someone else and asking for the privilege of kissing his feet. The imam wrote back to grant this false person an audience. Reza went to the imam’s home with gifts; fortunately no one recognized him. In the course of conversation, Reza brought up the treatise. He claimed he was pretty familiar with this Reza guy’s ideas, and since he’d heard the imam was so concerned about them, he just happened to have a copy of the treatise on him. The imam quickly figured out he’d been duped about what the treatise said and revoked the execution order. Reza then revealed his true identity and everything was fine. He never figured out who’d misrepresented his treatise to the imam, but in your fictional campaign, we all know it was the adventure’s villain.

Three months before the end of the expedition, Ekhtiyar, the head of the Iranian delegation, fell ill. Reza had to take over. He finalized the maps, planted the flags, and closed the border commission.

Source: Memories of a Bygone Age: Qajar Persia and Imperial Russia 1853-1902, translated and edited by Michael Noël-Clarke (2016). Despite its weird title, it’s Aqa Reza’s memoirs. By the end of his life, his name had expanded somewhat and he’d also picked up plenty of titles, for a final name of Mirza Reza Khan Danesh, Arfa’-Od-Dowleh, Prince Arfa’.