In 133 B.C., a Roman tribune named Tiberius Gracchus attempted to ram through a law redistributing land for the benefit of poor at the expense of the rich. The process was… contested. There were some exceptionally clever political maneuvers, several murders, and a wide array of skulduggery on both sides. It’s amazing inspiration for an RPG adventure!

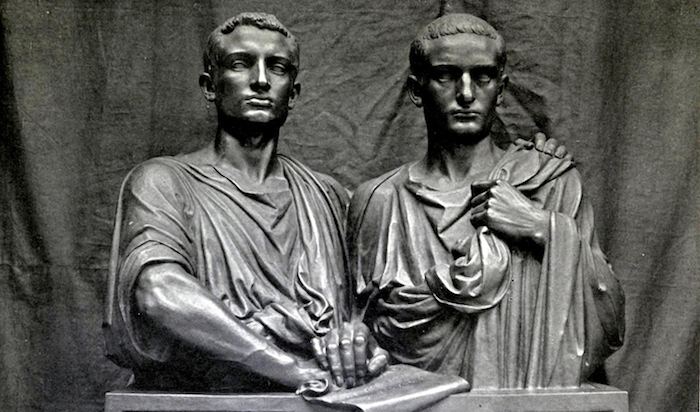

Tiberius Gracchus came from a notable military lineage. He was the grandson of the famous general Scipio Africanus (who defeated Hannibal) and the brother-in-law of Scipio Aemilianus, who destroyed Carthage. Tiberius was himself a war hero: the first over the wall at Carthage.

In 137 B.C., Tiberius traveled through the Roman countryside. He was shocked not to see many small peasant landowners. Instead, it seemed the land was divided among large estates, owned by the wealthy and worked by slaves taken prisoner in Rome’s wars. The soldiers who fought in those wars came from farming families, but returned home without farms of their own.

Interestingly, the archaeological evidence contradicts Tiberius’ view. The Italian countryside is littered with the remains of small farms from this era. It’s possible Tiberius misread the situation. It’s also possible he went looking for a cause to champion for his own political benefit – particularly one that would humiliate the wealthy Roman Senate. The Senate had previously humiliated Tiberius by refusing to ratify a treaty he negotiated while fighting in Spain.

In 134 B.C., Tiberius campaigned for the position of tribune. At the time, the Roman Republic had two tribunes. Each had the authority to propose legislation for all citizens to vote on. Each also had the authority to veto such laws. (The Roman Senate couldn’t pass laws, but had authority over foreign policy, the military, enforcing laws, and funding government programs.) Tiberius campaigned on a platform of land redistribution from the rich to the poor. At your table, the PCs might run the campaign of your Tiberius-analogue NPC, perhaps drawing from my post about local elections as adventures in Tarang, Nepal.

Once sworn in in 33 B.C., Tiberius immediately put a bill before the people reallocating ‘public land’ in the countryside. Theoretically, this land was available for everyone to use. In practice, the rich snapped it up for their estates. Tiberius’ bill would restrict estates on public land to 300 acres, freeing up land to be broken into small plots and allocated to poor families. He claimed the 300-acre maximum restored an old legal limit that Rome had abandoned. Justifying the reform as a return to past practice was a clever way to get around Romans’ strong traditionalist inclination.

(As a side note, if you don’t want to run an adventure about property redistribution – a contentious topic in the post-communist era – there’s nothing about this story that requires it to be about land reform. In your fictional setting, your version of Tiberius could be advocating for just about anything.)

The Senate did not like Tiberius’ proposal. And why should they? Some of the richest men in Rome were senators, and they didn’t want to see their estates shrink! They approached Rome’s other tribune, a wealthy man named Marcus Octavius, and got him to veto Tiberius’ bill. Repeatedly. Tiberius responded by organizing a successful campaign to vote Marcus out of office. Without Marcus’ opposition, the bill passed easily. At your table, the PCs might help recall Marcus – not by campaigning against him (they just ran a campaign, and doing the same thing twice is boring), but by ferreting out some crime or scandal in his background that would force prominent senators to drop their support for him.

The play and counter-play between Marcus and Tiberius was a standard bit of political maneuvering. But it also reflects a philosophical dispute in representative democracies that has never been resolved. Are elected officials delegates of the voters, bound to do what the people wish? Or are they representatives, exercising their own judgement and discretion on behalf of the people? Tiberius argued tribunes were delegates. Marcus argued they were representatives. Both claimed opinions that conveniently lined up with their political needs.

The next obstacle was funding. Surveying the public lands and reallocating them would be expensive. The wealthy men of the Senate couldn’t block Tiberius’ law, but they didn’t have to fund it. Conveniently, one of Rome’s client kings (Attalus III of Pergamum) chose that moment to die. In his will, King Attalus left Rome his kingdom, his estates, and his wealth. Tiberius convinced the people to approve a law that diverted this windfall. It wouldn’t enter the Roman treasury (which the Senate controlled) but would go directly to funding the redistribution of land. The Senate was furious, but powerless to stop this latest maneuver. At your table, the PCs might have a fun time traveling to a distant land to arrange a windfall like this one – either honestly or through deceit!

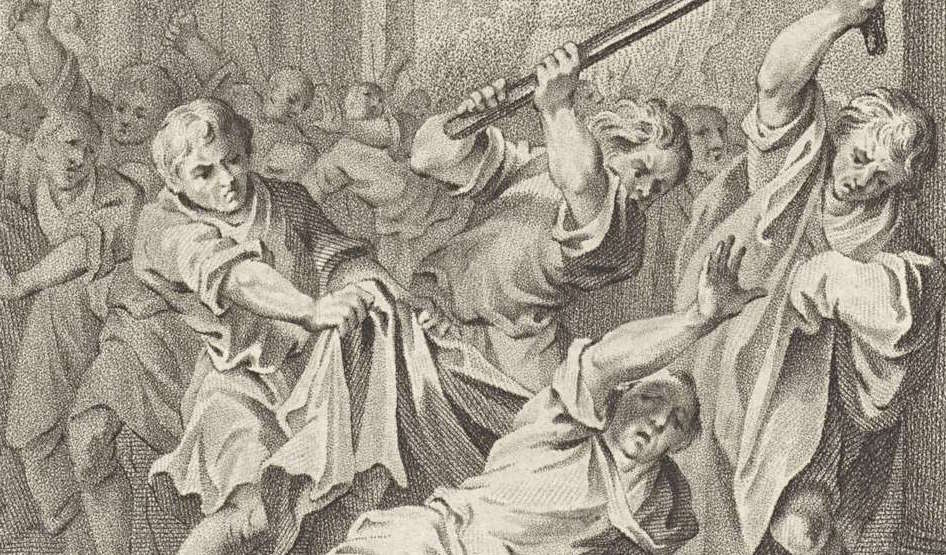

Tiberius ran for a second consecutive term as tribune. This was not unprecedented, but it was too much for Rome’s wealthy. They plotted to have him killed on election day. In a Roman election, thousands of adult male Roman citizens gathered in one place to vote. Tiberius was there, of course. So was a gang of senators and thugs, led by Tiberius’ own cousin. There was a brawl, and someone bludgeoned Tiberius to death with a chair leg. At your table, this is an opportunity for the PCs to leap into action! Can they save your version of Tiberius?

Then it was time for the fallout. The Senate sent Tiberius’ murderer on a convenient mission to Pergamum, where he’d be safe from retaliation. Some of Tiberius’ supporters were put on trial. We don’t know for what crimes. At least one was executed by being stuffed in a sack full of venomous snakes.

The pro-Tiberius faction got their murders in too. Tiberius’ brother-in-law Scipio Aemilianus returned from fighting in Spain to agitate in favor of wealthy families whose estates on public land were shrinking. He turned up conveniently dead on the morning when he was supposed to give a speech.

Interestingly, none of this retributive killing stopped the land redistribution. The law stayed in effect. Surveyors went out into the field, their salaries paid by King Attalus’ windfall. Archaeologists have even uncovered the boundary stones of the newly-divided plots of land. If your PCs fail to save your version of Tiberius, they lose a valuable ally, but his reforms still happen. They just become the coda of a tragedy, not a triumph that leads to greater objectives.

Also, a final note on violence in the political process: it escalated. Twelve years later, Tiberius’ younger brother tried to pass an even more radical series of reforms. Some succeeded, like subsidizing the sale of grain to keep it affordable, even during famines. But he and three thousand of his followers were murdered by the Senate for their trouble. Killing folks to silence them can work, but it risks backlash and sets a dangerous precedent. Remember that if your PCs want to engage in retributive violence at the end of this story.