The court hunts of the Mughal Empire in 16th-century India were remarkably gameable affairs, where the army beat the bushes to gather a forest’s worth of animals into a ring for courtiers to fight. They were also tools of geopolitics, used to quell rebellions before they arose. Money changed hands, hunters fought tigers and elephants, and councillors conspired for advantage. You couldn’t ask for a better gaming setting. Let’s look at the hunts of Akbar, the most hunt-loving of the Great Mughals!

This post is brought to you by beloved Patreon backer Justin Moor. Thanks for helping keep the lights on! If you want to help keep this blog going alongside Justin, head over to the Patreon page – and thank you!

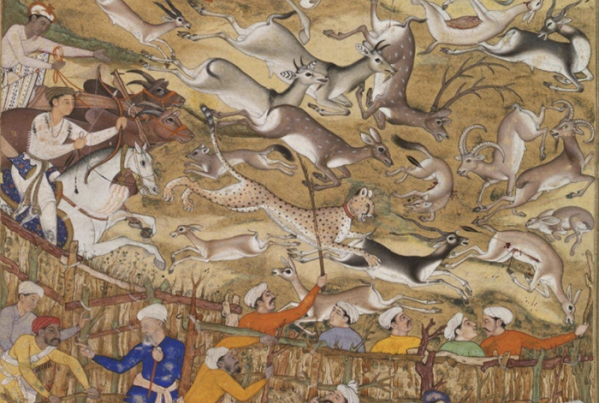

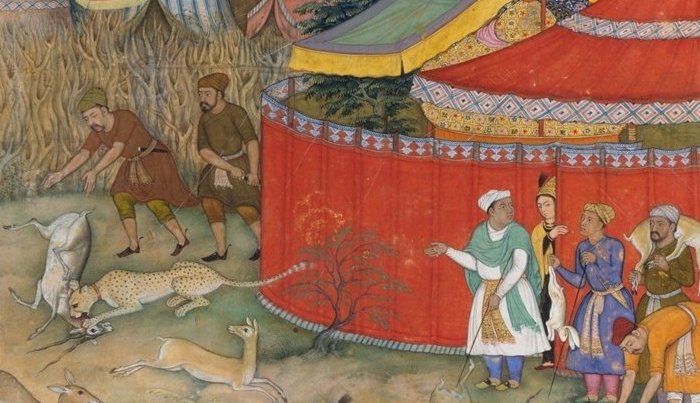

This style of hunting – called qamargah (“enclosure”) – involved taking a significant chunk of the Mughal army on expedition. At the destination, the army enclosed an area many miles in diameter, then spent days or weeks tightening the circle, driving the animals into a smaller and smaller space. Once the circle was small enough, the army erected wattle screens as a fence to keep the animals in. Then the emperor got to enter the enclosure – on horseback, in an elephant howdah, or on foot – to kill what he wanted. Then the nobles got to take turns, then the officials, then the soldiers. Towards the end, the killing fields were apparently crowded not just with animals, but also with hunters. Hunters carried weapons as varied as muskets, bows, lances, lassos, and even swords. And this was medieval India, so the animals to be killed weren’t just deer and antelope, but also tigers, lions, rhinos, elephants, and sloth bears.

Other animals in the enclosure were there working with the Mughals. They loved falcons, and they trained cheetahs to catch and retrieve prey. Elephants served as mounts, but they could also be goaded to fight other animals. Emperor Akbar, the most enthusiastic of the qamargah hunters (whom I’ve written about before), enjoyed riding elephants that he made fight other elephants.

As an example of Akbar’s hunts, in 1567, he had 50,000 soldiers enclose an area 60 miles in diameter. That averages one soldier every seven yards around the circle’s circumferance. Over a month, the soldiers constricted the area until it was only four miles across. Akbar hunted in the enclosure for five days before letting anyone else in.

These grand hunts were more than a lavish pastime for India’s most powerful. They were also a geopolitical tool. 50,000 soldiers on expedition is one hell of a statement, even if they’re ostensibly only there to scare some animals. If a province was starting to make noises like it might rebel, holding a hunt there was a great way to remind would-be rebels the foolishness of such an idea. If a neighboring prince was forgetting to publicly state that he acknowledged the Mughals as his sovereigns, holding a hunt near the border could get him to fall into line. Akbar even used hunts to conceal genuine military movements!

These enormous hunts were, of course, social occasions. The rich and powerful got drunk and partied. They placed bets on how things would go in the enclosure. They even used the opportunity to settle scores. More than one person was killed in a qamargah hunt in the guise of a hunting accident, especially towards the end when there were lots of hunters in the enclosure. Even without foul play, the enclosure was a dangerous place. Akbar himself, at age 54, grabbed a stag by the antlers and got gored in the testicles for his trouble.

At your table, a qamargah can be a great site for an adventure. You don’t have to fill the enclosure with mythical monsters, but goodness gracious why wouldn’t you? The PCs might be recruited to kill someone in the enclosure (even the emperor!) in the guise of a hunting accident. They might be asked to rig a bet by making sure that a certain person seems to kill more creatures in the enclosure than someone else. The PCs might even bet on themselves. Or the court spymaster might hear that rebels have guessed where the enclosure will be and hidden there to assassinate the emperor when he rides in. Can the PCs take care of them? Better yet, can they do it without anyone noticing – since the emperor is supposed to be the first to enter the enclosure, not the PCs?

At the end of the adventure, you can always springboard to another one by declaring that this hunt was actually a cover for a real military expedition, and the court is suddenly invading its neighbor!

The qamargah hunt also makes a really neat feature for a particular kind of player. You’ve always got players who really, really love combat. The biggest reason why they show up every week is the hope that they’ll get to fight something super cool. The qamargah is a great way to reward such a player by rewarding their character in-universe. The PCs did such a great job with something that the emperor is granting them the honor of being the first into the enclosure. Now the players get to fight the really cool monster that’s lurking in there – it rewards that particular player both in the fictional universe and in the play around the table.

Make sure you don’t miss a blog post by subscribing to my no-frills, every-other-week mailing list! I also have a signup that’s only for big product releases!

Looking for material for your game tonight? My back catalog has hundreds of great posts, all searchable and filterable so you can find something from real history or folklore that fits exactly what you need! Posts older than a year are behind a very cheap paywall – only $2/month!

Come follow and chat with me on social media! On Mastodon I’m @MoltenSulfur@dice.camp. On Twitter, I’m @moltensulfur. On Blue Sky, I’m @moltensulfur.bsky.social.

Enjoy this post? Consider sharing it on social media, or maybe emailing it to a GM friend of yours. The social media infrastructure that creators relied upon to grow their audiences is collapsing. You sharing my stuff helps me stay relevant and ultimately helps me get paid for my time.

Check out my book Making History: Three One-Session RPGs! It’s three awesome historical one-shots with pregenerated characters and a very simple rules system designed specifically for that story. Norse Ivory is a game about heritage and faith in the Viking Age. A Killing in Cahokia is a murder mystery in the Native American temple-city of Cahokia. And Darken Ship is a horror-adventure starring junior sailors on a U.S. Navy warship who wake up one morning to discover they’re alone on a ship that should carry three thousand.

Source: The Great Moghuls: India’s Most Flamboyant Rulers by Bamber Gascoigne (1971, revised 1998)